Seoul’s Strategic Sidestep: How South Korea’s Retreat Reshapes Indo‑Pacific Deterrence and Empowers Beijing

Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

On 31 March 2025, the People’s Liberation Army announced “Strait Thunder‑2025A,” a significant live‑fire drill that encircled Taiwan with ten warships and more than 80 combat aircraft. Over the next 48 hours, Taiwan’s defence ministry logged 59 warplanes and 23 vessels breaching its security zones, with eighteen jets crossing the median line that Beijing now rejects outright. This drill, which was easy to miss amid domestic economic headlines and a snowballing Middle‑East oil scare, turned a regional show of force into a geopolitical audition. China demonstrated how swiftly it could exploit a gap left by an ally’s policy retreat. The message landed not only in Washington and Tokyo but in every classroom, boardroom, and cabinet that still assumed deterrence in Northeast Asia was a settled equation.

From Regional Pivot to Pragmatic Recalibration

President Lee’s decision to strike the term “Indo‑Pacific” from his inaugural foreign‑policy platform reversed a decade‑long effort to knit South Korea into a security web stretching from the Sea of Japan to the Bay of Bengal. This shift, from a 'regional pivot' to a 'pragmatic recalibration', has significant geopolitical implications. Rather than extending the “global pivotal state” doctrine of his predecessor, Lee recast Seoul as a “pragmatic mediator,” eager to resume the Moon‑era New Northern and New Southern policies and to smooth over frictions with Beijing and Moscow. At first glance, the recalibration appeals to a war‑weary electorate and exporters rattled by US tariff threats. Yet diplomacy is never subtraction‑free: shrinking one strategic map invariably enlarges another. By stepping back from a multilateral framework that explicitly links Korean security to the Taiwan Strait, Seoul signals that Beijing may no longer face coordinated resistance should it test a blockade scenario.

Domestic politics partly explain the shift. January’s East Asia Institute poll shows that 44.6% of progressives favour expanding inter-Korean exchanges, while only 26.6% prioritise strengthening the US alliance; the mirror image holds among conservatives. Lee’s strategists read these numbers as a mandate to ease great‑power tension, not to tighten allied fronts. Yet those exact figures reveal a public split wide enough for external actors to exploit—Beijing included.

Numbers That Tell a New Balance

Quantitatively, Seoul’s tilt is already traceable. In May 2025, exports to China fell 8.4% year‑on‑year to $10.4 billion, yet China still absorbed nearly one‑quarter of Korean shipments, four points more than the US share. Semiconductor dependency deepens the bind: chips made up 21% of all Korean exports in 2024—$142 billion—of which China accounted for the most significant single slice. Meanwhile, Beijing’s defense budget climbed another 7.2% this March to 1.79 trillion yuan ($247 billion), outpacing GDP and marking its tenth consecutive year of single‑digit but compound growth.

Contrast that with Seoul. The 2025 national budget trimmed planned outlays to ₩673 trillion, yet still increased the military allocation to ₩61.2 trillion—approximately $46 billion, equivalent to barely 2.3% of GDP. Contributions to the US troop presence are expected to rise 8.3% to $1.47 billion under the existing Special Measures Agreement; however, even this figure faces renegotiation pressure as Washington links defense and trade talks.

Methodologically, the trade-exposure figures draw on monthly customs data aggregated by the OEC and validated against Bank of Korea export tallies. At the same time, defense budgets rely on appropriations bills and conversions to US dollars, as verified by Reuters, at quarter-average exchange rates. Where gaps exist—particularly in dual-use technology flows—we apply a conservative 10% margin of error band based on variance across Korea Customs and KITA disclosures. These guardrails underscore, rather than inflate, how Korea’s economic ballast still leans toward China even as its security ballast teeters.

The Taiwan Strait in Seoul’s Blind Spot

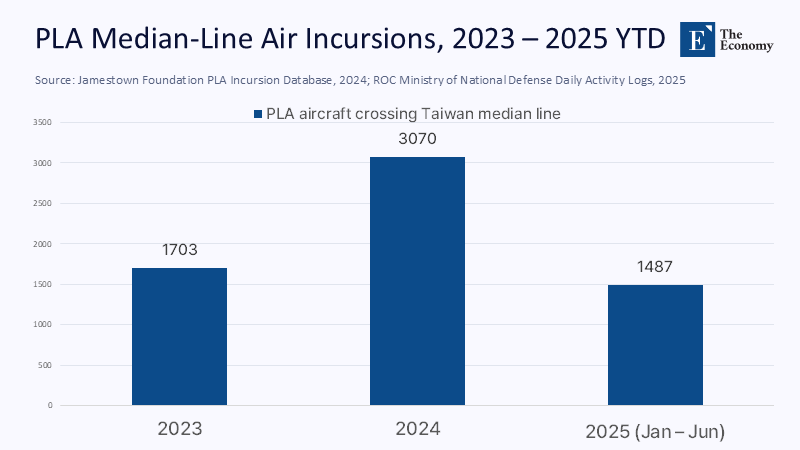

PLA aviation patterns amplify the risk. The Jamestown Foundation reports 3,070 individual Chinese sorties across the median line in 2024—up from 1,703 the previous year—and January 2025 alone saw a record 248. Each intrusion forces Taiwan—and, by extension, the United States and Japan—to consider response options that rely on Korean logistical cooperation for airlift, refueling, and command and control. Remove Seoul from that equation and Beijing gains time‑distance advantages: fewer allied bases on the northern arc, narrower ISR coverage, and a weakened narrative of united deterrence.

Critics argue that Lee’s stance buys Seoul leverage to mediate should a crisis erupt. Yet, leverage presupposes an equal perception of risk. Beijing’s calculus weighs rugged capability: it sees South Korea’s F-15 K squadrons re-tasked to Peninsula contingencies, not Taiwan; it sees Seoul skipping last month’s NATO summit, citing “domestic priorities,” and concludes that the political cost of coercing Taiwan has just fallen. That inference—whether accurate or not—shapes behaviour in real time, as every coercive rehearsal normalises the next.

Ripple Effects for Classrooms, Campuses and Cabinets

For educators, the policy pivot demands curricular overhaul. Diplomatic history courses that once presented South Korea as an Indo‑Pacific “swing hub” must now dissect a live case of deterrence diffusion. Administrators overseeing joint-degree and research exchanges with Taiwanese, Japanese, or Australian universities face heightened scrutiny of visas and funding as Beijing tests the loyalty of South Korean partners. Meanwhile, policy schools wagering on EU-Korea-NATO linkages must explain why Seoul’s absence in The Hague weakens arguments for cross-regional security rationalization.

At the government level, the semiconductor rescue package of ₩33 trillion will cushion exporters against US tariff shocks. Still, it also exposes a contradiction: Seoul hedges economically toward Washington while hedging strategically toward Beijing. Provincial education offices that depend on STEM partnership grants with US labs may find those funds tied to alignment metrics—such as attendance at alliance forums, data-protection standards, and even textbook language on Taiwan. Policy coherence, once an abstract debate, now touches school budgets and research pipelines.

Answering the Pragmatists: A Rebuttal

Proponents of the new pragmatism contend that engagement with China reduces Korean vulnerability to supply‑chain coercion and secures diplomatic channels with Pyongyang and Moscow. They note, correctly, that South Korea’s arms exports to NATO members, such as Poland, reached a record $14 billion last year and are unlikely to evaporate overnight. Yet, history warns that economic entanglement does not immunize states against geopolitical shocks.

The 2008 global financial crisis reduced Korean exports to China by 26% over four quarters; a blockade-induced spike in insurance premiums for Strait shipping lanes would dwarf that. Moreover, a Taiwan conflict would trigger immediate semiconductor export controls from Washington, freezing the very cashflows Seoul hopes to protect. The rebuttal therefore rests on layered evidence: first, that Korean vulnerability is systemic, not situational; second, that deterrence dilution raises the probability of the very crisis pragmatists seek to avoid; third, that a modest recommitment to multilateral exercises—short of full re‑adoption of the Indo‑Pacific label—would restore enough uncertainty in Beijing’s planning to preserve regional stability.

Closing the Gap Before the Strait Widens

If two days of drills can redraw perceptions of power, two years of strategic drift could rewrite realities. China’s sorties will not slow, its defence budget will not shrink, and its appetite for wedge politics will only grow so long as key allies step back. South Korea’s educators, administrators, and policymakers, therefore, share a common imperative: rebuild the intellectual and institutional muscle memory of allied coordination before the next rehearsal becomes the real event. The choice is not between pragmatism and partnership but between calibrated engagement and coerced accommodation. Seoul’s strategic sidestep need not become a strategic surrender—yet every semester, every budget cycle, every skipped summit inches the region closer to that line. The time to course‑correct is now.

The original article was authored by Dongkeun Lee, a Policy Fellow at the Asia-Pacific Leadership Network. The English version, titled "South Korea moves away from former Indo-Pacific Strategy," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

East Asia Forum. “South Korea Moves Away from Former Indo‑Pacific Strategy.” 21 July 2025.

East Asia Institute. 2025 Polls on Polarization and Democracy in South Korea. 19 March 2025.

Jamestown Foundation. “Military Implications of PLA Aircraft Incursions in Taiwan’s Airspace.” December 2024.

Korea Herald. “Lee to Skip NATO Summit amid ‘Various Domestic Issues.’” June 2025.

Observatory of Economic Complexity. “South Korea and China Bilateral Trade, May 2025.”

Reuters. “China Maintains Defence Spending Increase at 7.2%.” 5 March 2025.

Reuters. “China Conducts Exercises Around Taiwan.” 31 March 2025.

Reuters. “China Live‑Fire Drills in East China Sea Escalate Taiwan Exercises.” 2 April 2025.

Reuters. “South Korea Economy Likely Returned to Growth in Q2.” 22 July 2025.

Reuters. “South Korea Reaffirms Defence‑Cost Sharing Deal with U.S.” 9 July 2025.

Reuters. “South Korea Unveils $23 Billion Chip Support Package.” 15 April 2025.

South Korea Ministry of National Defense. Defense Budget Trends 1975‑2025. 2025.

US Air University. “Less Politics, More Military: Outlook for China’s 2025 Incursions.” April 2025

Comment