The Silent Price of Credibility: Unveiling the Influence of Fiscal Stability On Long-Term Interest Rates – and Why the Fed Can't Do It Alone

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Over the ten months leading up to July 2025, the United States made a staggering payment of approximately a trillion dollars in net interest on its debt. This amount surpasses the combined spending on many parts of the cabinet and continues to widen the overall deficit, despite the increase in tariffs. Even with customs duties doubling to $135.7 billion for the fiscal year to date, the interest expenses have managed to consume the gains and more. The national debt has now surpassed $37 trillion, a milestone reached years earlier than previous forecasts. The yield on the 10-year Treasury is hovering around the mid-1940s, with markets becoming increasingly sensitive to signs of persistent deficits. These events do not indicate an immediate crisis, but they do suggest a persistent premium on long-term lending that will not dissipate with short-term interest rate cuts. This underscores a political truth: Governments that consistently stabilize their finances face lower long-term interest rates over time, not because central banks give in, but because investors value predictability, a smaller future supply of bonds, and lower inflation risk.

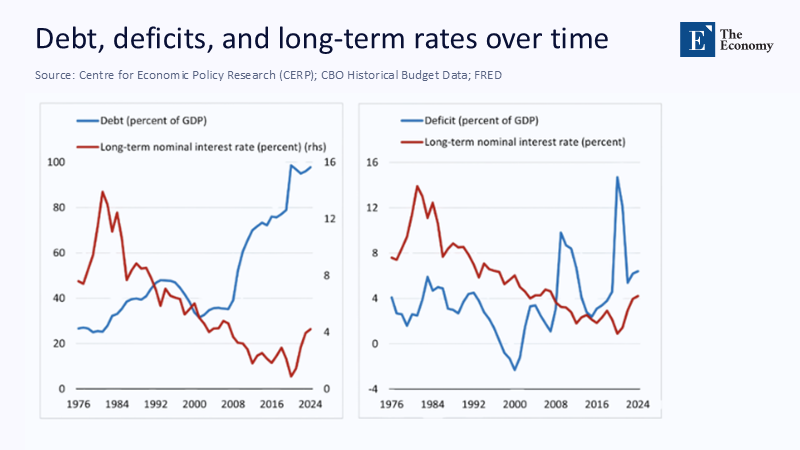

Redefining the debate: From "interest rates cause debt" to "debt shapes interest rates"

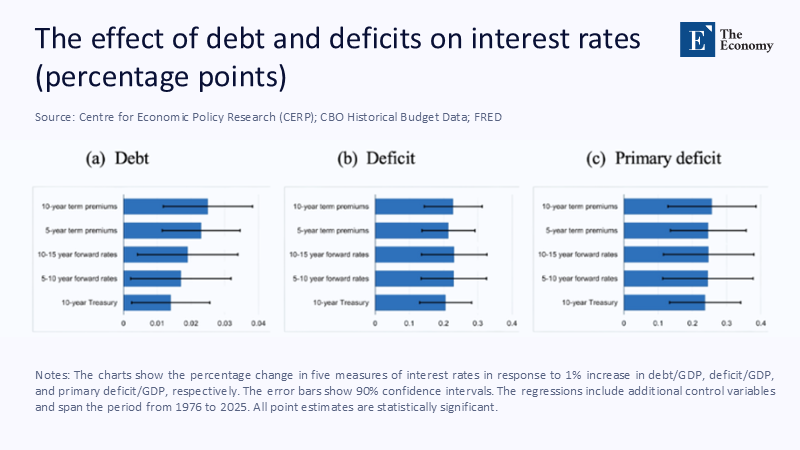

A well-known narrative suggests that high interest rates cause large deficits by inflating the government's interest rate bill. However, the two-way causal link is not the only policy lever at play. We often underestimate the opposite: persistent deficits and rising debt ratios push up long-term interest rates by raising expected future short-term interest rates and the duration premium. Recent empirical work, using long-term projections to mitigate endogeneity, finds that a one-percentage-point increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio increases government interest rates by about 2-3 basis points. In contrast, a one-point increase in the deficit-to-GDP ratio has an even greater effect because markets treat deficits as persistent. The conclusion is not that every increase in expenditure causes an immediate sell-off, nor that short-term monetary policy becomes irrelevant. It is the credible stabilization of the primary balance that reduces the compensation that investors demand over the long term. This effect is accumulating quietly but materially – and it is the horizon that determines the cost of mortgages, corporate financing, and the state's interest account.

The mechanism that matters: Expectations and the term premium

Long-term returns are equal to expected future short-term interest rates plus a duration premium. When fiscal trajectories seem unsustainable, both components can drift higher. First, markets conclude that, in the absence of reforms, future policymakers will tolerate higher inflation or higher real interest rates to place the debt burden. The swelling of the supply of government bonds and greater macroeconomic uncertainty are pushing the premium upwards. Daily estimates from the New York Fed show premium movements correlated with fiscal news. The Federal Reserve and BIS survey links higher debt and longer average duration to a modest but significant premium. In other words, budgetary credibility is a transmission channel of monetary policy: it squeezes the premium by reducing supply risk and macroeconomic uncertainty, and it links policy rate expectations because the central bank does not have to lean so hard against demand or inflationary pressures fueled by large, persistent deficits. The political conclusion is not heroic austerity; it is the improvements in the primary balance that the markets can price today.

What the Latest Figures Say: 2023-2025 Data Points We Can't Ignore

In all advanced economies, the relationship between fiscal pressure and long-term yields has been reaffirmed. France's long bond yields have climbed toward Italy's – a reversal of the old "core-periphery" hierarchy – as investors reassess deficits and policy execution risk. At the same time, Italy's consolidation signals have tightened spreads. In the US, the 10-year yield hovered near the mid-40s to mid-2025, even as short-term inflation eased, reflecting the lingering effects of long-term premiums and supply. Global borrowing has escalated to record levels, with OECD government bond debt projected to exceed $56 trillion in 2024 and corporate government bond debt exceeding $100 trillion, intensifying competition for savings. Meanwhile, the IMF and CBO predict debt ratios that continue to rise without policy change and interest costs that consume a growing chunk of GDP and revenues. The pattern is not uniform – demand for safe assets continues to exert downward pressure – but the message is clear: where fiscal fundamentals deteriorate, long-term interest rates resist gravity.

How significant is the fiscal result, practically? Transparent assessment

Suppose a government commits to and credibly executes a gradual improvement in the primary balance of 1% of GDP, maintained for five years, reducing the projected debt-to-GDP ratio by about 10 percentage points versus the baseline scenario in the early 2030s. Using the midrange of recent estimates – ~2-3 basis points for the 5y5y or 10y5y interest rate per 1 unit of debt to GDP – this consolidation would reduce very future interest rates by 20-30 basis points once it is priced. Because very future pricing affects current yields on 10-year and 30-year bonds, we should expect a comparable decline in long-term bond yields over time, with a pass-through to housing loans and investment-grade borrowing costs. On the budget side, a conservative rule of thumb says that every 25 basis point drop in average borrowing costs reduces federal net interest by about $50-70 billion per year over a few years, depending on the rollover rate and maturity mix. This saves compounds; it's not a panacea, but it slows down essentially the dynamics of debt without raising taxes or cutting benefits overnight.

Policy translation: The Key to Reducing the Term Premium is Credibility, not pressure on the Fed

Calls for "interest rate cuts" confuse the horizons: central banks set the short-term end, markets put the long-term end based on inflation, growth, and fiscal credibility. Political pressure on a central bank—no matter how strong—rarely convinces 10-year bond yields over a long period, and may even increase them if it undermines institutional independence. The United States offers a live test. Despite public pressure on the Fed and administrative pressures for lower interest rates, markets have focused on the path of deficits and debt, seeing tariff revenues rise but still overshadowed by overall spending and interest costs. The lesson is simple: a credible fiscal anchor – clear primary balance targets, resilient PAYGO rules, debt-to-GDP protective rails, and an independent debt manager that optimizes maturity – drives long-term yields more than monetary policy. Frontloading growth reform financing, combined with retroactive and contingent resolution triggers, can alleviate short-term pain while reducing the premium that investors are asking for for a holding period.

Anticipating the Reviews: Japan, Ricardian Equivalence and the Tariff Temptation

Three objections are repeated. Firstly, 'Japan denies the connection'.Japan's decades-long low yields along with high debt reflect unique characteristics – domestic investment base, central bank balance sheet policies, deflationary shift – that are not generalized. In economies with higher potential growth, external financing needs, and fewer captive holders, the effect of debt on long-term interest rates is more substantial. Second, the Ricardian equivalence claims that households offset deficits by saving more, and sluggish interest rate effects. However, the literature and recent US data show measurable base unit movements linked to debt and deficits, particularly at very advanced interest rates, where current saving behavior is less critical than institutional credibility. Third, 'tariffs finance the gap'.The July data show that customs receipts are jumping, but remain small except for interest and mandatory expenditure, and carry inflationary and growth trade-offs that can raise expected policy rates and term premiums. The axis that matters is not a basic revenue instrument; it is the direction and persistence of the primary balance.

The Long-Term Short-Term Gap: What the Fed Can and Can't Do

A central bank can lower inflation expectations and smooth out the cycle, and in this way, influence the expected path of short-term interest rates that are embedded in long-term yields. But when fiscal policy forecasts rising debt and persistent primary deficits, a non-trivial chunk of long-term performance reflects the hedge for future supply and policy risk beyond the direct competence of the central bank. The ACM premium series captures this: premium increases often coincide with fiscal and government news, while sustained reductions follow episodes of reliable consolidation and sound funding strategies. Even if the Fed cuts the policy rate at the front end, long-term yields may not follow sustainably unless markets believe that the fiscal anchor will be maintained. Over the next decade, the CBO and independent analysts expect that the share of the budget absorbed by interest will continue to increase in the absence of reforms. This arithmetic is what investors are pricing in long-term interest rates today. Monetary credibility is essential; fiscal credibility is crucial.

What does a reliable fiscal anchor look like in practice?

A functional anchor has four elements. First, a debt-to-GDP protective railing – for example, a slide path to stabilize near current levels within five years and then decline – combined with escape clauses only for severe recessions or wars. Second, the primary balance governs this harsh bias towards sustainability: PAYGO with a high-quality score, caps on low-multiplier spending, and an end to temporary tax breaks. Third, an issuance strategy that normalises supply and reduces the risk of passing-on: measured extension of the average maturity while maintaining liquidity in benchmarks; explicit coordination between the Ministry of Finance, debt managers and macroeconomic authorities to avoid sudden fluctuations in the duration supply; fourth, growth-sensitive investments; closely linked to productivity – allowing for pro-growth capital expenditures that pass an independent cost-benefit test and expire automatically if multipliers underperform. None of this requires sudden austerity. It requires predictability strong enough for markets to reduce risk premiums and for households and businesses to plan with confidence. Credibility is an inexpensive asset until it is wasted; Then it becomes expensive to buy back.

The cheapest interest rate cut is a believable budget

The number that opened this column is not destiny; it is a policy forecast. If investors conclude that the primary balance will improve and the debt ratio peaks instead of rises, a quietly substantial repricing begins: forward interest rates are relaxed, maturity premiums are squeezed, and the state's interest bill is reduced, freeing up space for public priorities without higher taxes or steep cuts. No government can talk to the markets about this outcome, and no central bank can plan for it for the long term. Markets require a budget path that they can guarantee. This means measurable, legislated steps that start moderately, steadily deteriorate, and survive the elections. The reward is not an overnight dip in yields, but a lower baseline scenario that permeates mortgages, municipal bonds, and business investments. At a time of high global borrowing and an aging population, the only viable way to bring down long-term interest rates is to win – by making fiscal stability more than a slogan and letting the credibility do the silent work it will never do.

The original article was authored by Davide Furceri, the Division Chief in the Fiscal Affairs Department of the IMF, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Re-evaluating debt and deficits inducing high interest rates in the US," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2025). Annual Financial Report 2025. Basel: BIS.

Bureau of the Fiscal Service, US Treasury (2025). Monthly Treasury Statement (MTS) and Federal Spending Data.

Congressional Budget Office (2024). Reviewing the relationship between debt and long-term interest rates (Working Paper 2024-12). Washington, DC: CBO.

Congressional Budget Office (2025a). Budget and economic perspective: 2025-2035. Washington, DC: CBO.

Congressional Budget Office (2025b). The long-term financial perspective: 2025-2055. Washington, DC: CBO.

Congressional Budget Office (2025c). Monthly budget review: July 2025. Washington, DC: CBO.

Commission for a responsible federal budget (2025a). "Interest on debt will exceed $1 trillion next year."

Commission for a Responsible Federal Budget (2025b). "The cost of interest could explode from high interest rates and more debt."

Dallas Fed (Plante, M. et al.) (2025). Review of the Impact of Federal Debt Interest Rates (Working Paper 2513). Dallas: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York (2025). "Cash Term Premiums (ACM)."

US Federal Reserve Board (Gust, C. et al.) (2024). Government debt, limited projections, and long-term real interest rates (FEDS 2024-027). Washington.

FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2025a). "Return on purchase of U.S. Treasury securities at 10-year fixed maturity (GS10)."

FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2025b). "10-Year TIPS Performance (DFII10)."

IMF (2025a). World Economic Outlook Database. Washington.

IMF (Furceri, D., Goncalves, C., &; Li, H.) (2025b). The impact of debt and deficits on long-term interest rates in the US (WP/25/141). Washington.

Laubach, T. (2003/2004). "New data on the impact of budget deficits and debt on interest rates". US Federal Reserve (FEDS 2003-12).

OECD (2025). Global Debt Report 2025. Paris: OECD.

Peterson Foundation (2025). "Interest Cost on National Debt: Monthly Tracker."

Reuters (2025a). "High yields bring the U.S. fiscal cliff even closer." May 29, 2025.

Reuters (2025β). "The US deficit increased to $291 billion. in July despite the increase in tariff revenues." August 12, 2025.

Financial Times (2025). "France's borrowing costs are approaching Italy's borrowing costs as investors worry about debt." August 14, 2025.

CNN (2025). "White House Escalates Pressure on Powell and the Fed to Cut Interest Rates." July 10, 2025.

Luck (2025). "In Trump's year of cost-cutting and effectiveness, the national debt exceeds $37 trillion." August 13, 2025.

VoxEU/CEPR (2025). "Reassessment of Debt and Deficits Causing High Interest Rates in the US". August 14, 2025.

Comment