Currency, Many “Colors”: Why Tokenisation — Not Crypto — Will Rewire Payments

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In 2024, the European Central Bank conducted a groundbreaking six-month experiment. It settled over 200 wholesale transactions, amounting to a staggering €1.59 billion, across 58 diverse use cases on distributed-ledger rails in central bank money. This real-world application of tokenisation showcased its potential in transforming the financial landscape. In 2025, the Bank for International Settlements reported that 94% of central banks are now exploring CBDCs or related digital-money infrastructure. Industry estimates suggest that shifting today’s post-trade processes to tokenised, programmable rails could unlock $15–$20 billion in annual cost savings and free up roughly $100 billion in trapped collateral. None of those numbers hinge on speculative cryptocurrencies; all of them flow from bringing regulated money—central-bank reserves, commercial-bank deposits, and highly liquid funds—onto programmable ledgers. The policy signal is equally clear: the U.S. Congress’s GENIUS Act of 2025 sets strict guardrails for privately issued “payment stablecoins,” while regulators in Europe and Asia push pilots that keep settlement anchored to public money. The economic story here is tokenisation, not crypto.

From Hype to Plumbing: Reframing What “Digital Money” Actually Means

The last decade flattened two very different ideas into one word. “Crypto” referred to bearer-style assets native to public blockchains, designed to sit outside the banking system. “Tokenisation,” by contrast, is a technique for representing existing legal claims—deposits, Treasuries, money-market shares—on programmable platforms. The economic stakes diverge. Crypto’s market value may swell or contract with risk appetite, but its macro impact on payments has been narrow. Tokenisation, however, re-platforms the money we already use, compressing time in settlement, synchronising delivery-versus-payment, and enabling conditionality (“pay on delivery,” “release on proof”). In the U.S., the GENIUS Act clarifies the status of payment stablecoins and (crucially) tempers their bank-like features, underscoring that private tokens do not carry the monetary finality of central-bank money. Policy is drawing a bright line: programmable forms of fiat get priority over volatile crypto-assets. The practical payoff is fewer reconciliations, less trapped collateral, and a single money account.

What Tokenisation Changes in the Real Economy

Tokenisation streamlines messaging, clearing, and settlement into a single programmable state machine. The BIS blueprint terms this the unified ledger: a platform where central-bank money, tokenised deposits, and tokenised assets transact atomically. The concept of composability is crucial: complex, multi-step financial workflows—such as escrow, collateral substitution, and coupon payment—execute as a single instruction, reducing the risk of failure and operational drag. The ECB’s 2024 wholesale DLT experiment demonstrated that this is not just a theoretical concept; it is already feasible at a production-like scale. In this design, settlement finality is derived from the presence of central-bank money, not from proof-of-work mining or speculative token economics. This structural shift leads to fewer intermediated hops, fewer reconciliation cycles, and fewer daylight-overdraft exposures. The ledger is always active, but the liabilities it moves are familiar and regulated. The economic impact stems from improved plumbing, not from the creation of a new currency. These practical benefits underscore the real-world applicability of tokenisation.

A Single Currency, Many “Colors”: Purpose-Bound Money Without Fragmentation

The strongest policy intuition behind tokenisation is simple: keep one unit of account, but allow context-specific rules. Think of today’s fiat as a spectrum of “money colors.” All euros are euros, all dollars are dollars—but a token carrying a rule that says “spendable only on public-transport passes” or “escrows until delivery confirmed” behaves differently without breaking par. Singapore’s Project Orchid operationalised this with purpose-bound money (PBM): a protocol that binds conditions to transfers across different digital monies, from tokenised deposits to potential retail CBDC, through a standard interface. The result is programmability without balkanising the currency. For governments, that means vouchers and grants with built-in safeguards. For institutions, it means automated spending controls and auditable disbursements. The core discipline is interoperability: tokens redeem 1:1 into conventional accounts, preserving singleness while enabling fine-grained policy design.

Evidence, Not Evangelism: What the Numbers Say

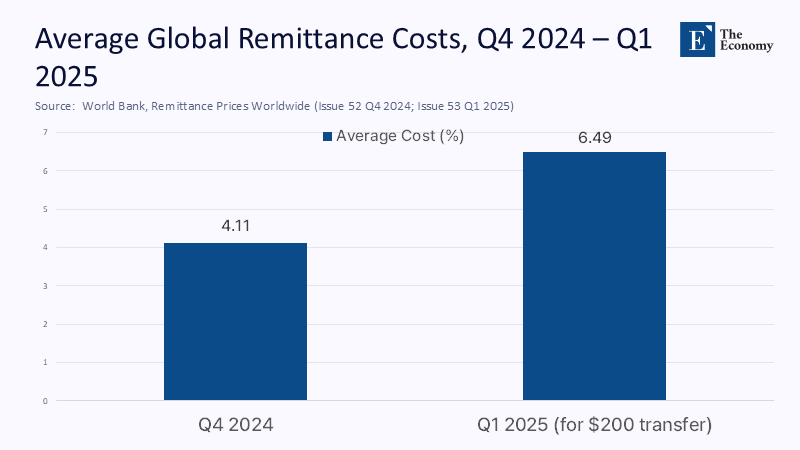

Two key data points underscore the potential of tokenising the safe end of money. First, the persistent cross-border frictions we endure are costly. The World Bank’s Remittance Prices Worldwide data for Q4 2024 revealed that the global average cost to send $500 was 4.11%; by Q1 2025, the average price for $200 had risen to 6.49%. These figures reflect the layers of correspondent banking, FX spreads, and compliance overhead. Programmable, atomic settlement that eliminates intermediated hops can significantly reduce these costs, particularly in high-volume corridors. Second, tokenised cash-like instruments are gaining traction: tokenised money-market funds in the U.S. had amassed an estimated $7 billion AUM by June 2025, while custodians and asset managers are formalising tokenised liquidity pipes. This activity is not about speculative returns; it's about enhancing the utility of institutional cash as collateral and settlement medium across ledgers. The potential for significant cost savings is a compelling argument for the adoption of tokenisation.

To translate those macro estimates into sector arithmetic, consider a university network that processes €200 million in international tuition and research-grant flows annually. If tokenised rails reduce value-at-risk by one business day at a conservative 4% annual funding rate, the opportunity cost saved is roughly €21,900 per day of float avoided; extended across peak intake periods and grant cycles, those savings stack. If the same rails cut reconciliation and exception-handling costs by even 20% against a €2 million payments-operations budget, the steady-state run-rate saving is €400,000. The methodology is transparent: we apply observed float rates and operational spending to the specific steps tokenisation compresses—funding windows, failed settlements, and manual reconciliations. The point is not precision to the euro; it is that programmable settlement monetises time and certainty in ways traditional batch systems cannot.

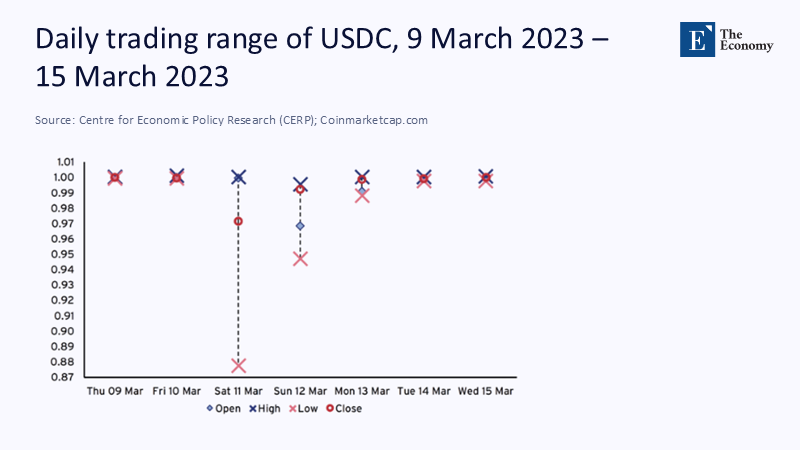

Drawing the Right Regulatory Line: Stablecoins vs Tokenised Deposits

The policy path that maximises economic gain while minimising systemic risk prioritises tokenised deposits and wholesale CBDC over retail stablecoins. The BIS has cautioned that stablecoins struggle to meet money’s “no-questions-asked” singleness, and can fracture liquidity—especially in stress. The GENIUS Act, enacted in July 2025, places payment stablecoins under stringent constraints and underscores the importance of interoperability with banking infrastructure rather than crypto ecosystems. In parallel, major banks are piloting tokenised deposits—most notably J.P. Morgan’s permissioned JPMD for institutional clients—precisely to move cash on-chain without exiting the regulatory perimeter. The direction of travel is consistent: policy embeds programmability inside the monetary system instead of competing with it from outside. This is also why central banks are focusing on wholesale rails first; anchoring tokenised settlement to reserves makes both prudential and operational sense. The emphasis on regulatory guardrails is a key factor in ensuring the stability of the financial system in the era of tokenisation.

Of course, regulation must keep tokenised liabilities from morphing into unregulated money-like instruments. Europe’s recent wholesale DLT work, the Bank of England’s consultation response on a digital pound, and industry-led schemes like the Regulated Liability/Settlement Network all converge on the same design choice: par-redeemable tokens issued by supervised institutions, settled against central-bank money, with robust KYC/AML. Programmability is welcome; shadow deposit-taking is not. A clear taxonomy—CBDC for public money, tokenised deposits for bank money, tokenised funds for savings—draws lines that technologists can implement and supervisors can supervise. That architecture leaves room for innovation on public or private ledgers, without sacrificing monetary sovereignty.

What This Means for Education Systems and Public Administrators

Education is a payments-intensive business: micro-payments from millions of students, cross-border tuition flows, grant disbursements tied to milestones, and procurement across long supply chains. Tokenisation maps cleanly onto these realities. Purpose-bound tuition tokens can release funds to universities only upon confirmed enrolment, then auto-refund prorated balances if a student withdraws before the census date. Research-grant “escrow tokens” can disburse on verified deliverables—dataset deposited, pre-registration posted, ethics approval logged—reducing ex-post clawbacks. Supplier invoices can be settled instantly on delivery with atomic proof, tightening cash conversion cycles for small vendors without exposing the university to pre-payment risk. For international students, tokenised rails combined with competitive FX can shave points off remittance costs that still average 4–6% depending on corridor and ticket size. The institutional upside is less working capital trapped in the process and fewer compliance surprises, audited continuously by the ledger’s state transitions.

Administrators should start with tokenised deposits from existing banks, not consumer-facing stablecoins. Banks already hold the treasury accounts, know the counterparties, and can map tokens 1:1 to account balances, preserving insurance and legal clarity. Where available, wholesale CBDC proofs-of-concept can be used for high-value settlements—bond-funded campus projects, for instance—so that payment and delivery of tokenised municipal paper are atomic. Meanwhile, student-aid agencies can pilot PBM vouchers redeemable at accredited institutions and categories of spend (tuition, textbooks, housing) without introducing paternalism: tokens remain euros or dollars, just colored by policy rules that the student sees in their wallet. The first KPI is not “blockchain adoption” but failed-payment rates, average settlement time, and exception-handling costs—metrics CFOs already track.

Anticipating the Critiques—and Answering Them

One critique is that programmability invites brittleness: if code is law, what happens when real life deviates from the script? The World Economic Forum has called this the “paradox of programmability”: automation removes human discretion even as it reduces manual risk. The answer is not to abandon rules but to write revocation and override routines into the protocol and governance. Another critique is that tokenised deposits could accelerate bank runs by enabling instant, automated withdrawals. This is a design problem, not a fatal flaw; holding-limit and tiered-access features, already contemplated in CBDC work, can modulate flows in stress. The most common critique—“we already have instant payments”—misses that RTP/PIX/UPI rails still reconcile against account-based ledgers, leaving post-trade and collateral stuck in yesterday’s workflows. Tokenisation’s edge is settlement synchronisation across money and assets, which instant messaging alone cannot offer.

A final concern is fragmentation: dozens of bank- or fund-specific tokens that don’t talk to one another. Here, the regulatory guardrails bite hardest. The BIS blueprint presumes interoperability by design: common message standards, shared settlement assets, and bridging where multiple ledgers exist. The ECB’s DLT work and the Bank of England’s focus on wholesale experiments suggest a pragmatic path—start with central-bank money as the common denominator, then allow private-ledger diversity where it adds value. As pilots mature, supervisors can mandate APIs and token standards the way they standardised ISO 20022 messaging. The goal is a network of networks, not a winner-takes-all chain.

One Currency, Many Colors—Time to Act

The numbers that opened this essay point to a plain conclusion. When regulated money goes programmable, the economy gets faster, safer settlement, and lower operational drag, without gambling on unbacked assets. That is why central banks are experimenting with DLT while keeping their monetary anchor; why lawmakers are constraining stablecoins to narrow, interoperable roles; and why banks and asset managers are tokenising deposits and cash-like funds rather than minting their own currencies. For education systems and public agencies, the payoff is concrete: fewer reconciliation headaches, faster vendor payments, more innovative grants and aid disbursement, and better risk controls—one currency, many colors. The policy choice is not crypto versus the state; it is programmable fiat within the state’s monetary perimeter. If leaders treat tokenisation as infrastructure, not ideology, they can cash in on the only returns that matter at scale: saving time, freeing collateral, and turning compliance into code.

The original article was authored by Stephen Cecchetti and Kermit L. Schoenholtz. The English version, titled "Crypto, tokenisation, and the future of payments," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2023). Annual Economic Report 2023, Chapter III: Blueprint for the future monetary system.

Bank of England & HM Treasury (2024). Response to the Digital Pound consultation.

Banque de France (2025). Tokenised money market funds: implications for financial stability.

CoinGecko (2025). Global crypto market cap, August 2025.

Congress.gov (2025). GENIUS Act of 2025 – Bill text.

European Central Bank (2025). Annual Report 2024.

J.P. Morgan (2025). Kinexys pilots first USD-denominated deposit tokens (JPMD).

Monetary Authority of Singapore (2022). Project Orchid report: Purpose-Bound Money.

Reuters (2025). BIS delivers stark stablecoin warning; pushes tokenised “unified ledger”.

VoxEU/CEPR (2025). Crypto, tokenisation, and the future of payments.

WEF (2024). Understanding tokenisation’s $15–$20 billion savings and $100 billion collateral unlock.

WEF (2024). ‘Code as law’: the tokenisation of financial assets and the paradox of programmability.

World Bank (2024–2025). Remittance Prices Worldwide — Issue 52 (Q4 2024) and Issue 53 (Q1 2025)

Comment