The New Grain Price Floor: Why Post-War Ukraine Won't Reset the Clock

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Before the conflict, Ukraine produced approximately 33 million tons of wheat at its peak in 2021. Currently, both official agencies and independent observers anticipate that production will stabilize in the low-20 million ton range for the foreseeable future—even if hostilities cease—due to the changes in the agricultural landscape. By the end of 2024, around 139,000 square kilometers of Ukrainian land may be contaminated with mines and unexploded devices; extensive farmland needs to be surveyed and cleared. The destruction of the Kakhovka dam has eliminated irrigation for up to 600,000 hectares in the country's southern agricultural region, with satellite images revealing that feeder canals are visibly drying up. Additionally, nearly 6.9 million Ukrainians are currently living abroad, while 3.7 million are internally displaced, resulting in a reduced agricultural labor force. These issues are not just seasonal; they represent long-term challenges that significantly increase the costs associated with producing and transporting grain from the Black Sea. A global expectation for 'pre-war prices' is unrealistic given these mathematical realities. However, with proactive policy and investment, we can navigate these challenges and ensure a sustainable future for Ukraine's agricultural sector.

From shock to structure: recasting the price narrative

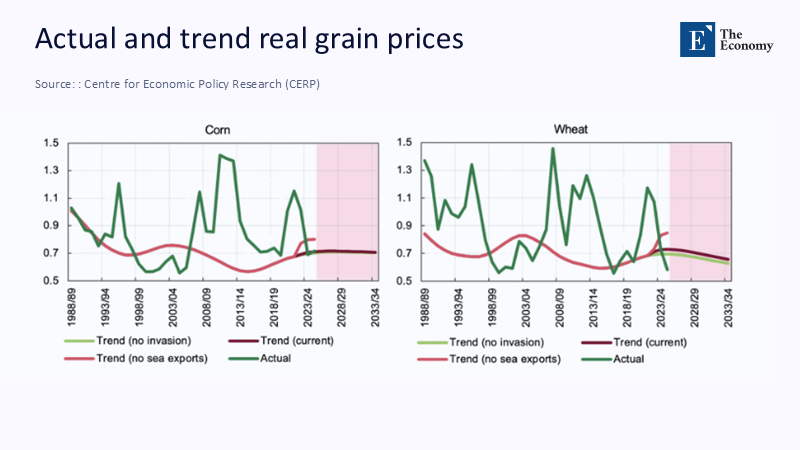

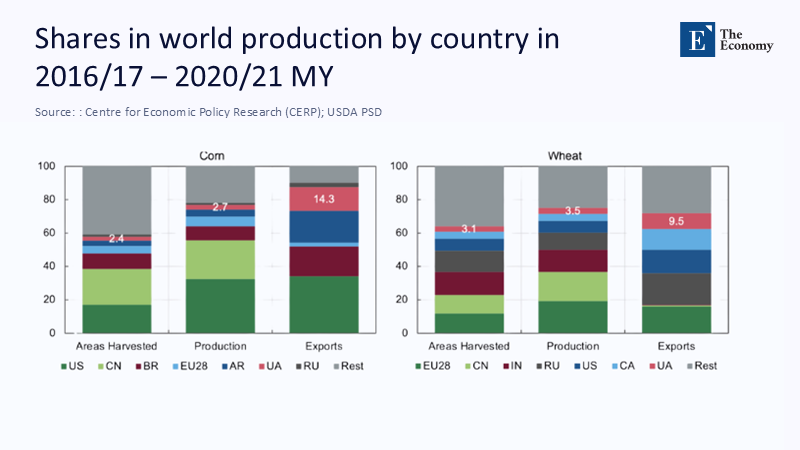

Early commentary framed wartime grain inflation as a shock that would unwind once shipping lanes reopened and Russian exports normalized. That framing missed how the war rewired the determinants of price. Recent empirical work finds that, even with global supply recovering elsewhere, corn and wheat prices are likely to remain above their pre-invasion trajectories because regional disruption has altered storage, timing, and risk premia embedded in markets. Spot indices corroborate the shift: the FAO Cereal Price Index in mid-2025 sits below 2022's spike yet continues to reflect a world of elevated volatility; and relative to January 2020, wheat prices, while modestly lower in mid-2025, have not returned to the low pre-COVID trend that planners used to assume. The key point is not that prices are "high" every month, but that the floor has risen. A structural premium persists because production, logistics, and insurance along the Black Sea now carry permanent frictions that forecasting models must encode rather than treat as transitory noise.

The land cannot spring back: mines, irrigation loss, and soil reality

Grain yields are a function of land quality and water. Both have been degraded at scale. Mine-action reviews reclassified Ukraine in 2024 from 'heavily' to 'massively' contaminated; the government's Action Plan identified roughly 470,000 hectares of farmland as immediate demining priorities and returned only a portion to production last year. Irrigation loss from the Kakhovka dam blast is not a one-season detour: estimates suggest nearly 600,000 hectares lost access to controlled water, with NASA imagery documenting canal systems desiccating across Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. Even where fields are safe to till, years of shelling, heavy machinery traffic, and flood-then-drought cycles have disturbed soil structure. Agronomy offers tools—cover crops, amended rotations, regenerative practices—but rebuilding topsoil structure and organic matter is measured in multi-year cycles. Demining alone costs in the tens of billions of dollars; irrigation networks require targeted capital and scarce materials. This is a long-term recovery process that requires patience and understanding, and it's why the country's wheat area has shrunk by roughly a quarter from pre-war levels and why the rebound has stalled well below the 2021 benchmark. Land has turned from an abundant factor into a bottleneck.

The missing hands and know-how: displacement's quiet drag

Agriculture is not just land and inputs; it is people who read the weather, maintain implements, and manage risk. Ukraine's farm economy supplied about 14% of jobs pre-war and a large share of export income. Today, millions are outside the country or uprooted within it. Displacement not only shrinks headcount; it breaks teams and tacit knowledge networks. A combine harvester without a seasoned operator is a depreciating asset; an irrigation district without its technicians is a map line. Training replacements takes seasons, not weeks. This human capital shock is compounded by psychosocial stress, uneven access to finance, and a partial exodus of young rural families toward cities or abroad. The result is a lower adequate capacity even when headline acreage looks stable. Policymakers sometimes assume that labor returns with peace, but refugee surveys suggest stepwise repatriation and sectoral re-sorting, not a snap-back. That means the productivity wedge between fields that exist and fields that can be efficiently farmed will persist—and with it, the marginal cost of Ukrainian grain.

Corridors, insurance, and the costlier mile

Logistics amplified the land shock into a price floor. Ukraine reopened a de facto Black Sea corridor in late 2023, and volumes have improved. Yet the corridor is stitched together under active threat, and the attacks on Odesa-region ports and Danube facilities mean freight cannot be priced like "normal" export flows. Insurers have been blunt: war-risk add-ons rose into the 0.6–1.0% of hull value range at the height of escalations (and spiked above 1% after notable strikes). Kyiv's Marsh/Lloyd'sLloyd's facility has helped, but premiums remain materially above peacetime norms, and coverage can tighten overnight. The cost shows up in basis: the same ton of wheat loaded at Chornomorsk carries a risk levy that a ton at Rouen does not. Infrastructure damage also bites. Since 2022, Russia has conducted dozens of attacks on port infrastructure and vessels; Ukraine's ports increased total cargo transshipment by 57% year-over-year in 2024 to 97.2 million tons, yet that was still roughly 37% below the 2021 pre-war level. Rail and road solidified as backstops, but they are costlier per ton-kilometer than deep-water capacity. This isn't a bridge back to the old price; it is a detour with tolls.

Production arithmetic: a lower ceiling and a higher floor

The production math is unforgiving. USDA data show Ukraine's harvested wheat area falling from roughly 7.4 million hectares in 2021/22 to about 5.0–5.5 million hectares since, with output settling near 22–23 million tons—about a third below the 2021 record. That gap equates to several percentage points of world export availability, given Ukraine's pre-war ~10% share of global wheat trade. Global supply elsewhere has responded—South American maize and North American spring wheat, for example—but the world is now clearing at a higher marginal cost. Commodity sheets show U.S. HRW and SRW wheat prices in 2025 well below 2022's2022's panicky highs yet not anchored to 2019's low base, and international outlooks still project record cereals with inventories tight by historical standards. In other words, headline abundance coexists with a new geography of risk. The trajectory has changed: empirical work flags that post-invasion dynamics continue to push both level and variance above the old track. A peace agreement would ease volatility; it would not conjure land, labor, and logistics back to 2021 conditions overnight.

Policy translation: treat affordability as a design constraint, not an afterthought

For education systems, municipal buyers, and humanitarian agencies, the right lesson is not to stockpile hope but to redesign procurement and nutrition programs for a persistent premium. School meal budgets and university dining contracts should incorporate price bands that assume a multi-year "Ukraine risk" in Black Sea wheat and sunflower supply chains. Where feasible, diversify origin exposure by shifting partial volumes to alternative exporters even at slightly higher freight to smooth variance. For national policymakers, the demining-irrigation nexus is the single highest-return rebuild dollar in European food security; it merits dedicated, independently audited channels linked to measurable hectares cleared and canals restored. Insurers and export-credit agencies can extend the corridor's risk-sharing architecture beyond grain, but they need predictability; that requires hardening port and rail nodes against attack and building redundancy. Finally, do not ignore upstream cost-push: recent EU tariffs on Russian fertilizers are strategically defensible yet raise near-term nitrogen costs; cushioning vulnerable producers through targeted vouchers can blunt pass-through into bread prices without backsliding on the sanctions regime. None of this restores 2019 prices, but it does protect the real purchasing power of school cafeterias and social safety nets.

Anticipating and answering the pushback

Two critiques recur. The first argues that global harvests will swamp regional losses, forcing prices back to pre-war norms. The second insists that once conflict ceases, investors will flood Ukraine with capital, eliminating the cost wedge. Both are overly linear. Yes, the International Grains Council sees record cereals in 2025/26, but those totals hide geographic and quality variations and do not erase the embedded risk premia in Black Sea logistics. Even under benign weather, the cost of clearing mines, rebuilding irrigation, retraining operators, and insuring ships persists across multiple budget cycles. Likewise, capital cannot compress time: the International Mine Action Review upgraded Ukraine's contamination severity; even under best-case financing, clearance and safe-farming protocols take years. Investors will help raise the ceiling on future harvests; they will not lower next year's floor for delivered wheat. The prudent planning assumption, then, is not "back to 2019," but "forward to a world where the marginal ton is a bit dearer and a lot more path-dependent."

Tie-back and call to action

The undeniable reality is that the conflict in Ukraine's agricultural region has formed from a stabilizing agent for prices to a force that establishes a price floor. Mines scattered across fields, dried-up canals, damaged port facilities, and a loss of skilled operators have all contributed to an increase in the baseline cost of a global essential. The statistics already illustrate the situation: production is significantly below the peak seen in 2021, shipping volumes through the corridors are still under prior war levels, and a risk premium continues to persist. Instead of hoping for a miraculous return to the past, educational leaders and public procurement officials should plan for an elevated baseline and protect vulnerable populations from its impacts; donors and governments ought to prioritize funding for demining and irrigation projects first; and market regulators must recognize that risks associated with Black Sea insurance and infrastructure have now become fundamental factors in price determination, rather than mere side notes. The more quickly we shift from longing for the past to proactive planning, the better our chances are to maintain Ukraine's school meals, ensure the reliability of humanitarian supply chains, and keep political discussions focused on the realities of recovery—rather than on unrealistic expectations from bygone days, Russia's

The original article was authored by Olga Bondarenko, a Senior Economist in the International Economy Analysis Unit of the Monetary Policy and Economic Analysis Department of the National Bank of Ukraine.. The English version, titled "From battlefield to market: How disruptions in Ukraine affected grain price trends," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

AP News. (20Ukraine's. Russia launches 4th aerial attack in a week against Ukraine's grain-exporting region.

Bondarenko, O. (2025, Aug. 24). From battlefield to market: How Russia's invasion of Ukraine affected grain price trends. VoxEU (CEPR).

CEPR

CSIS. (2024, Nov. 25). Russia's renewed attacks on Ukraine's grain infrastructure: Why now, what next?

CSIS. (2024, Dec. 5). Demining Ukraine's farmland: Progress, adaptation, and needs.

CFR. (n.d.). How Ukraine overcame Russia's grain blockade. Council on Foreign Relations.

European Parliament Research Service. (2024). Ukrainian agriculture: Damages, losses, and rebuild costs.

FAO. (2025, Aug. 8). FAO Food Price Index edges up in July.

GMK Center. (2025, Feb. 12). Cargo transshipment in Ukrainian ports in 2024 increased by 57%.

NASA Earth Observatory. (2023, Jul. 26). Canals in Lloyd's are drying up.

Phys.org. (2024, Feb. 5). How the Russian invasion of Ukraine has impacted the global wheat market.

Phys.org. (2025, Jan. 14). Study shows how Ukraine war impacts global food supply, pricing.

Reuters. (2024, Mar. 1). Ukraine expands ship war insurance with Marsh & Lloyd's.

Reuters. (2025, Aug. 22). European farmers face higher costs after EU tariffs on Russian fertilizers.

UNHCR (USA for UNHCR). (2025, Feb.). Ukraine refugee crisis: Aid, statistics, and news.

The Monitor. (2025, Mar. 5). Ukraine: Impact—landmine contamination estimates (end-2024).

USDA FAS IPAD. (2025). Ukraine wheat area, yield, nd product on historical series and 2025/26 forecast.

USDA FAS (Kyiv Post). (2025, Apr. 18). Grain and Feed Annual—Ukraine (UP2025-0010).

USDA FAS. (2024, Jan. 30). Grain and Feed Quarterly—Ukraine. (Corridor exports Aug–Dec 2023 ≈ 10 MMT).

World Bank. (2025, Jul. 2). Commodity Markets "Pink Sheet" (monthly)—wheat HRW/SRW prices.

World Bank / EC / UN / Government of Ukraine. (2025, Feb. 25). Ukraine—Fourth Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (RDNA4).

World Bank (blog via ReliefWeb). (2025, Jun. 13). Food Security Update. (Wheat vs Jan 2020 baseline).

Comment