Google Makes Third Request for High-Precision Map Data — Calls Map Regulations an Unfair Practice

Input

Modified

Third Request Following 2007 and 2016 High-precision maps at a 1:5000 scale is necessary for accurate navigation guidance The government is considering risks of leaking national security and classified information.

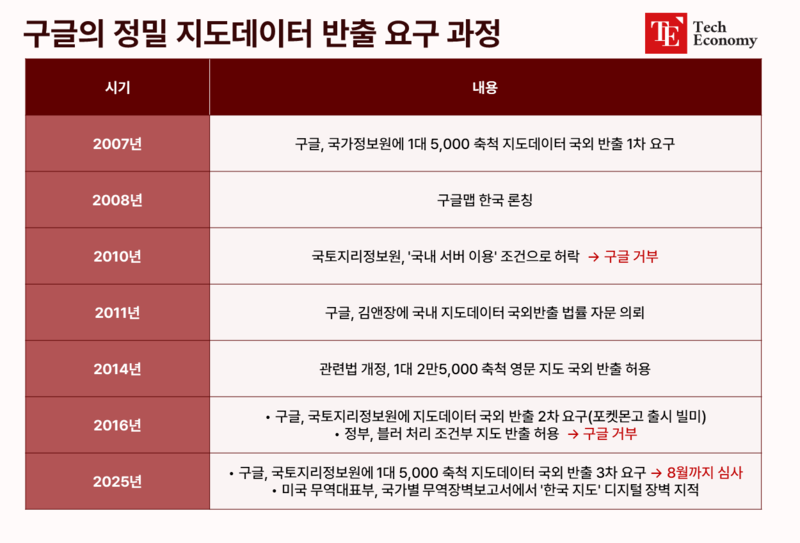

For the third time since 2007, tech giant Google has knocked on South Korea’s door, once again requesting permission to export the country’s high-precision map data to its overseas servers. The latest application, submitted in February 2025, marks nine years since the company’s last attempt in 2016.

The maps Google seeks are nothing short of meticulous — scaled at 1:5,000, they translate 50 meters of real-world distance into just a centimeter on screen. With that level of detail, not just streets but narrow alleyways and the contours of individual buildings are clearly defined. These maps are a far cry from the 1:25,000 scale Google Maps currently uses in South Korea, and Google says this limitation is a serious inconvenience — especially for foreign tourists.

According to the company, the reduced accuracy of Google Maps in South Korea disrupts navigation for international visitors, who often rely on the global-standard app for travel. In the absence of high-precision data, only public transit routes are supported. Driving, walking, or cycling directions? Not an option. Tourists must instead turn to domestic apps like Naver Map or TMap, and switch them to English — a workaround Google calls inefficient. It also notes that South Korea remains the only OECD member that restricts the export of map data overseas.

Global Standards vs. National Security

But there’s more than tourist convenience at stake. South Korea has rejected Google’s requests twice before — each time citing national security. The government’s position is shaped by the unique tension on the Korean Peninsula, where detailed geospatial information could, if paired with satellite imagery, be misused to target sensitive military installations.

Back in 2016, the government offered a compromise: Google could export the data if it built a data center on Korean soil, blurred military and security-related sites, or used domestically filtered versions of the maps. Google, however, dismissed the proposal, stating those conditions were “not subject to negotiation.”

Today, Google maintains nearly 30 data centers across 11 countries, including Taiwan, Japan, and Singapore. It is expanding in Thailand and Malaysia — but South Korea remains conspicuously absent from that list. This time around, though, Google appears more flexible. In its latest request, the company indicated it is willing to comply with the demand to obscure sensitive facilities — a notable shift from its earlier stance.

Still, unresolved concerns persist. Granting Google’s request would mean handing over the exact coordinates of every sensitive site — essentially, critical security information would be entrusted to a foreign corporation. A study published in the Journal of the Korean Cartographic Association warns that when high-resolution maps are layered with satellite images, it’s possible to uncover strategic military routes and supply lines, such as those within the Capital Defense Command. That’s why, to date, the South Korean government has never approved such exports — not even to industry titans like Apple or BMW, who also had their requests denied.

What’s more, Google’s current application doesn’t explicitly guarantee that sensitive sites will be blurred at the government’s request. If the data is transferred and Google changes its internal policy later, Seoul would be left with no legal mechanism to enforce its conditions. The company still has no plans to build a Korean data center either. Instead, it has proposed appointing a point-of-contact and establishing a hotline — a crisis-only phone line — to address any issues that may arise. For some officials, that may not be enough.

Google's Softer Approach and the Influence of Shifting Global Dynamics

Many analysts see Google’s persistent lobbying not as a matter of convenience, but as part of a larger ambition — building out its global "Google ecosystem." A key pillar in this vision is Android Automotive, the company’s in-car operating system that blends navigation, real-time data, and entertainment. In global markets, this system already ties into map-based advertising — pushing promotions to users as they pass by certain locations.

High-precision mapping, therefore, isn't just about routes — it's the foundation for future technologies: self-driving cars, drone delivery systems, and the sprawling Internet of Things (IoT). To train those systems and perfect those services, Google needs data — and lots of it.

Recent geopolitical developments have added new pressure. On March 31, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) issued its 2025 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers. In it, the USTR criticized South Korea’s map data restrictions as a “digital trade barrier” — a label that plays directly into Google’s argument. The company has long maintained, through formal channels like the USTR, that the export ban is a form of non-tariff trade obstruction.

These concerns are especially sensitive now, as the Trump administration recently imposed 25% tariffs on South Korean exports — despite the two countries' longstanding free trade agreement and military alliance. Some worry that Seoul’s continued resistance to Google’s request might become another justification for trade penalties down the road.

Decision Looms in the Months Ahead

The fate of Google’s request now lies in the hands of the Map Export Review Council, a multi-agency body that includes representatives from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Ministry of Science and ICT, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Unification, Ministry of National Defense, Ministry of the Interior and Safety, Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, and the National Intelligence Service.

By law, the council must make a decision within 60 days of receiving a request — though it is allowed one extension of equal length. In 2016, Google’s application filed in June was extended and ultimately rejected in November.

With the latest application submitted in February 2025, the final verdict on Google’s third attempt to export high-precision map data — its “third round” — is expected sometime between July and August.