Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Factories do not go dark when a tariff slaps the badge on a finished SUV; they flicker when the microchips, alloy blanks, and chemical reagents that feed every assembly line are taxed instead. The proper fulcrum of twenty-first-century trade power lies upstream, in the invisible lattice of intermediate goods that crosses the Atlantic half a dozen times before a consumer sees a price tag. Touch that lattice, and the shock reverberates through output, wages, and investment far beyond the border post. This piece argues that upstream tariffs are the economic equivalent of severing an artery. In contrast, downstream levies are little more than surface bruises; the European Union must resist the temptation of mirror-image retaliation and instead wield targeted measures that squeeze Washington politically without throttling Europe’s industrial bloodstream.

The Blind Spot in Tariff Debates

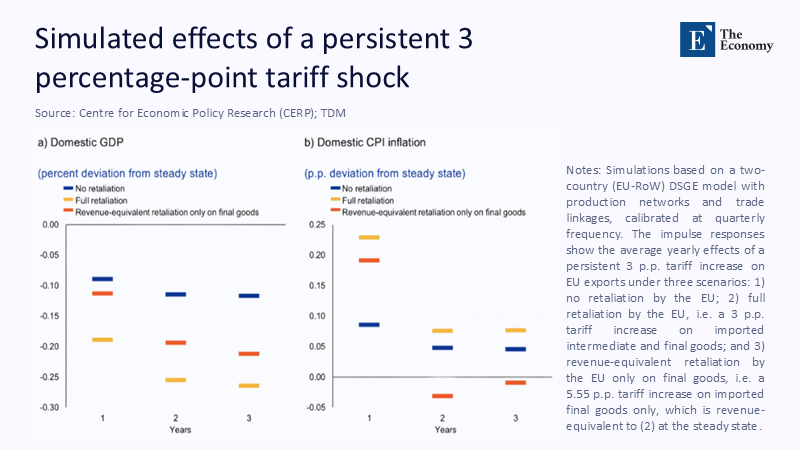

Protectionism almost always arrives dressed as a border tax on the shiny merchandise shoppers see in store windows. Yet, the real damage is inflicted higher up the production ladder, where invisible components flow back and forth across the Atlantic several times before a single good reaches a shelf. Recent CEPR modeling confirms what many trade economists have quietly suspected: duties on finished products barely dent aggregate output because firms re-route orders for chips, castings, and circuit boards the way water finds new channels in a river delta, whereas tariffs on those upstream inputs transmit cost shocks through every stage of value-added, wiping out multiples of the revenue they raise.

Final-Good Levies: Loud but Mostly Hollow

The United States' 2018 safeguard on imported washing machines is a cautionary tale. The average retail prices jumped significantly, and even dryers, a complementary good not directly affected by the tariff, saw a price rise. This pushed the consumer tab to a staggering €1.4 billion in the first year. However, the policy only netted €82 million in Treasury receipts and generated about 1,800 domestic jobs. This implies a more than €760,000 subsidy per position, an atrocious return on public pain. The episode illustrates how a border tax on finished goods can reshape commercial relationships more than it reshapes macroeconomic outcomes.

Input Tariffs: The True Shock Amplifiers

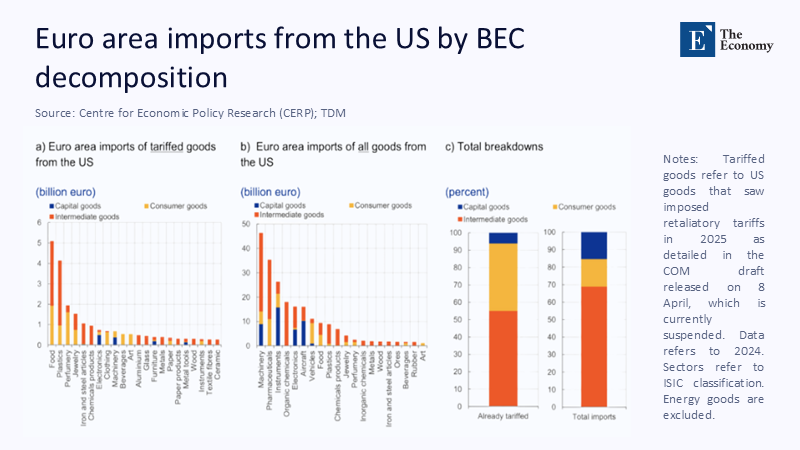

Now contrast that with levies targeting intermediate goods. An IMF input-output exercise finds that a ten-percentage-point hike on imported components slices nearly three times more value off national income than an equivalent duty on consumer products because every widget passing through the factory gate incorporates the taxed item repeatedly. The vulnerability is even starker in Europe, where intermediate inputs account for half of extra-EU exports and 59% of imports. Put differently, European firms make and buy an annual €1.5 trillion-plus worth of parts and sub-assemblies that might cross the Atlantic multiple times before appearing in a car, jet engine, or vaccine vial. Blocking that arterial flow with tariffs is the economic equivalent of inducing a cardiac arrest rather than a nosebleed.

Trump 2.0 and the New Protectionist Escalation Ladder

The stakes escalated in late May when President Donald Trump doubled tariffs on steel and aluminum from 25% to 50% and threatened a sweeping 50% levy on all European goods should negotiations stall. Equity markets immediately punished auto stocks—Toyota, Stellantis, Ford, and GM each fell around 3%—as analysts penciled in a five-percent surge in vehicle production costs. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick sought to downplay the legal turmoil surrounding several adverse court rulings, yet confirmed that Trump may pull the trigger on the broader tariff package as early as 9 July. If the White House moves from rhetoric to regulation, the EU faces the prospect of a tariff where it hurts most: the cross-border arteries of its industrial heart.

Quantifying Europe's Exposure

Eurostat records show that the Union exported €2.58 trillion in goods to non-EU destinations last year, of which roughly €503 billion went to the United States. Assuming the intermediate-goods share holds steady at 50%, €250 billion-plus of EU-made inputs could soon carry a 25–50% border tax. A back-of-the-envelope calculation illustrates the danger. If American buyers pass through even 80% of a 25% tariff to European suppliers—and TiVA studies put the pass-through closer to the full over two production rounds—the immediate hit to EU invoice values would approach €50 billion. Apply a conservative 1.8 input-output multiplier, and the loss climbs toward €90 billion, or 0.4% of Union GDP. By comparison, the aggregate welfare loss when only consumer goods were taxed in 2018 never crossed 0.15% of GDP. The message is not subtle: move the tariff upstream, and the economic damage triples.

Why Reflexive Retaliation Courts Self-Harm

In 2018, Brussels answered Washington's aluminum and steel duties with a mirror-image package covering €6.4 billion in U.S. motorcycles, bourbon, and blue jeans. The politics were cathartic, but the economics were negligible because those goods mattered little to European supply chains. Today, a tit-for-tat approach risks hitting European firms that rely on American software modules, aerospace alloys, or biotech reagents—the intermediates the Single Market cannot quickly replace. Therefore, the retaliation that mirrors the U.S. move would deepen the supply-chain injury the original tariff causes rather than offset it.

The Anti-Coercion Instrument: Europe's New Playbook

Fortunately, the Union need not swing the same blunt weapon. The Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI), in force since 27 December 2023, authorizes the Commission to deploy counter-measures ranging from procurement blocklists to visa restrictions and financial services suspensions, calibrated in real-time and scaled sector by sector. The regulation's architecture recognizes that twenty-first-century economic coercion travels through regulatory bottlenecks—capital-market access, data flows, technical standards—rather than customs posts alone. It hands Brussels a scalpel capable of drawing diplomatic blood without severing Europe's arteries.

A Strategy Tailored to Presidential Incentives

Writing in IP Quarterly, Markus Jaeger argues that any European response should aim directly at the U.S. president's political calculus rather than swing-state constituencies that can no longer restrain White House trade policy. He proposes three complementary tactics. First, threaten measures that rattle financial markets—temporary limits on euro clearing for U.S. banks or sovereign-bond custodian services—because recent episodes show Trump backs down when Wall Street shudders. Second, concentrate visible but low-spillover duties on emblematic consumer luxuries such as Tennessee whiskey or high-end SUVs, where European substitutes abound, maximizing political optics while minimizing supply-chain collateral damage. Third, keep digital services taxes and public procurement bans in reserve, signaling a credible ladder of escalation that compels negotiation without foreclosing an off-ramp. This emphasis on the potential impact of the proposed response is designed to make the audience feel the situation's urgency and the need for a strategic approach.

Scenario Analysis: Surgical Retaliation Versus Reciprocation

Suppose Brussels pairs a narrowly targeted 25% duty on €3 billion of high-margin U.S. spirits with an ACI-based suspension of euro-clearing for a handful of U.S. investment banks, contingent on market volatility thresholds. Historical price-elasticity data suggest the spirits levy would claw back roughly €600 million in U.S. export value—symbolic but headline-grabbing. The clearing suspension, by contrast, could raise overnight funding spreads for U.S. dealers by eight basis points, a pinprick reverberating through derivative markets where the president's donors and political barometers reside. Crucially, neither step impedes the flow of semiconductors, composite resins, or pharmaceutical precursors that European factories depend on. Compare that with a mechanical €10 billion tariff covering American aerospace and electronics parts: the latter might generate splashy headlines, but it would ricochet through Airbus fuselage assembly lines in Toulouse and SAP server farms in Walldorf within weeks. The surgical option, therefore, wields greater negotiating leverage at a fraction of the domestic cost.

Maintaining EU Unity

Retaliation must also pass the unanimity test among 27 member states with divergent exposure profiles. Germany fears auto tariffs; France worries about aircraft orders; Sweden's concern is data adequacy. The modular and reversible ACI measures allow Brussels to shield sensitive intermediate-goods sectors by carving them out of counter-packages, placating capitals that would otherwise veto a blunt customs tariff. The Commission's newly created Enforcement Task Force can model sector-specific spillovers in real time, publishing impact tables that help national parliaments visualize winners and losers before voting. That transparency was absent in 2018 and is indispensable today.

Beyond Tariffs: Regulatory Convergence as Counter-Leverage

Tariffs are only one axis in an era where standards and compliance regimes decide who sells what in the world's richest consumer market. The Union could, for example, fast-track conformity assessments for U.S. medical devices if metal tariffs are lifted—or slow-walk them if talks collapse. It could align cybersecurity certification for cloud services as a carrot or treat data-localization waivers as a stick. Because upstream industries care far more about predictable certification timelines than a percentage point on customs duty, these measures bite precisely where final-good tariffs do not.

Smarter Beats Harder in Twenty-First-Century Trade Defense

The data speak with one voice: taxes on final goods create headline noise but limited macroeconomic harm; taxes on intermediate inputs magnify pain along every production stage and can drag whole sectors into recession territory. The retaliation that mimics upstream tariffs, therefore, amounts to economic self-harm. Instead, Europe now possesses both the analytical evidence and the legal architecture to answer aggression precisely, pressuring the White House where its sensitivities lie in financial markets and political optics while insulating the supply chains on which European prosperity rests. That strategy demands discipline but offers a viable path back to negotiation and away from escalation. In an era when protectionist threats can materialize overnight, the Union must demonstrate that it can defend itself without endangering its industrial bloodstream. Tariff wars are won by those who know where to apply pressure, not those who swing the biggest club.

The original article was authored by Nicolò Gnocato, an Economist at European Central Bank, along with four co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Tariffs across the supply chain," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bruno, R., G. Caporale, and J. Hall (2024), "Global value chains and the transmission of trade shocks: Evidence from input-output linkages", Journal of International Economics, 138: 103660.

Cavallo, A., R. Gopinath, B. Neiman, and J. Tang (2019), "Tariff passthrough at the border and at the store: Evidence from US trade policy", American Economic Review: Insights, 1(2): 19–34.

European Commission (2023), Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of the Union and its Member States from economic coercion by third countries, COM(2021) 775 final, Brussels, 8 December.

Jaeger, M. (2024), "The EU should change its approach to countering Trump's tariffs", Internationale Politik Quarterly, 8 April.

IMF (2024), "Decoupling and Supply Chain Fragmentation: Implications for Global Trade and Growth", IMF World Economic Outlook, April.

Rauch, J. E. (1999), "Networks versus markets in international trade", Journal of International Economics, 48(1): 7–35.

TDM and ECB Staff (2024), "The distributional and macroeconomic effects of EU–US trade tensions", CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP18733, May.

TDM and Authors' Calculations (2024), "Figures and decompositions of EU imports and tariff impacts", Background Dataset for CEPR Column on Supply Chain Tariffs, April.

Wong, B., and P. Zipkin (2023), "Intermediate inputs and the fragility of global trade", Review of Economic Dynamics, 47: 100989.