Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

When the Kremlin closed the Nord Stream valves in 2022, Europe’s dilemma stopped being informational and became strictly physical. Kilowatt‑hours had vanished, not knowledge. No matter how many real‑time dashboards policymakers might have installed, they still would have faced the same brutal accounting identity: you cannot burn a spreadsheet for heat.

The seduction of perfect information – and its blind spot

Fetzer, Shaw & Edenhofer argue in VoxEU that the state’s “informational boundaries” channeled policy: Germany, armed with granular gas‑meter data, rationed and subsidized selectively; Britain, lacking that granularity, slapped on a universal price cap. Better data flows, they claim, could have produced a cheaper, more thoughtful response.

That view misdiagnoses the constraint. In 2022–23, the binding variable was not who paid for energy or how muchthey paid but whether the molecules existed at all. Europe had lost roughly 55 billion cubic meters of Russian pipeline gas—about one‑third of its pre‑war supply. Substituting that volume required physical infrastructure (LNG terminals, storage caverns, spare tankers) that did not exist. No amount of clever targeting would have magicked it into being.

Germany and Britain: opposite levers, convergent pain

Consider the two largest gas‑burning economies in Europe:

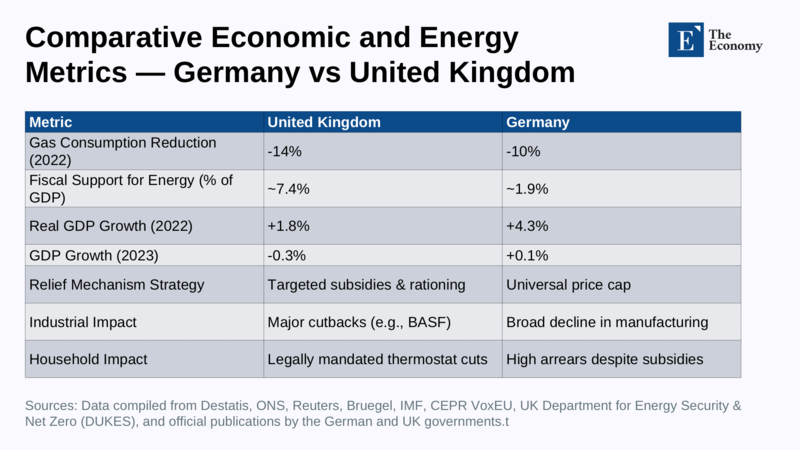

- Germany cut total gas demand by 14 % in 2022 through industrial curtailments and household thermostat limits.

- Britain trimmed demand by roughly 10–12 % while financing a blanket Energy Price Guarantee whose projected net cost was about 1.9 % of GDP.

Berlin spent roughly €264 billion (~7.4 % of GDP)—on its “economic defense shield” than London did on its universal cap. Yet outcomes converged:

- Real German GDP grew 1.8 % in 2022 but shrank 0.3 % in 2023.

- UK GDP grew 4.3 % in 2022 and managed only 0.1 % in 2023.

Two wildly different toolkits—fiscal transfers versus hard rationing—produced the same macro picture: near‑zero growth and surging public frustration. The reason is straightforward: both societies were dividing up a smaller pie. Whether you slice it thinly (demand cuts) or borrow against it (price caps), the pie does not enlarge.

The contrast between Germany and the UK, two of Europe’s largest gas consumers, is often framed as a choice between rationing and spending. But the results tell a different story. Despite divergent approaches, both economies endured the same energy scarcity and economic malaise. The table below summarises their key macroeconomic and policy responses between 2022 and 2023 — and illustrates that neither information nor ideology could escape the constraints of physics.

In short, different instruments—thermostats or Treasury cheques—did not change the outcome: both governments faced the same energy hole, and both economies stalled in response.

What more data could (and could not) have done

Could richer information have improved policy at the margin? Absolutely:

- Fairer targeting. With household‑level usage histories, Westminster could have aimed its support at low‑income, high‑intensity consumers instead of capping everyone’s bill.

- Peak‑shaving incentives. Real‑time tariffs tied to smart meters might have flattened evening spikes, stretching storage by a few extra days.

- Fiscal efficiency. A granular voucher scheme would have cost tens—not hundreds—of billions.

However, none of those tweaks would have restored the 14 % German demand or the 11 % UK supply that vanished. When the constraint is volumetric, allocation tactics are second‑order.

The deeper failure: strategy outran resilience

Europe’s political choice to back Kyiv was morally coherent yet materially reckless. In 2021 Russian gas still supplied roughly 40 % of continental imports; Germany’s industrial base depended on it for feedstock and heat. Brussels and Berlin guaranteed an output hit by moving to sever that link before alternative capacity was built.

Critics counter that Germany could have diversified earlier, or Britain could have insulated homes faster. True—but irrecoverable in the eight‑month window between invasion (February 2022) and winter. An LNG terminal needs two to three years, even on a crash schedule; deep retro‑fits take skilled labor Britain has not yet trained. The die was cast long before the data gap mattered.

Policy lessons that still stand when the pipes run dry

- Infrastructure first, dashboards second. A data-rich policy becomes powerful only once spare molecules exist to allocate.

- Mandate high storage floors. Had EU law required a 90 % fill by 1 October, the bloc could have coasted through early 2023 without panic buying.

- Treat LNG berth slots as insurance, not arbitrage. Idle capacity costs millions; emergency cargoes cost billions.

- Embed resilience thresholds in foreign policy. Do not threaten your supplier until you can survive the cut‑off.

- Price shock risk ex‑ante. Capacity payments for firm low‑carbon power (nuclear, hydrogen‑ready turbines, advanced geothermal) are cheaper than bailing out industry after the shock.

A final reckoning: energy is sovereignty

The information‑optimist narrative is alluring because it promises mastery without sacrifice: if only the dashboards had been bigger and the models sharper, Europe might have sailed through. The lived reality shows otherwise. Germany amassed Europe’s deepest industrial science—but when the gas stopped, BASF still idled its ammonia lines. Britain owns some of the world’s best economists—yet households still queued at food banks under a price cap.

Data steer choices within a feasible set; energy abundance defines that set. Lose the kilowatt‑hours, and every choice contracts to a menu of unpleasant options: consume less, pay more, or print debt. 2022–23, Europe sampled all three and discovered a hard limit to informational governance.

Until the continent builds physical redundancy—pipes, caverns, terminals, dispatchable clean power—the next geopolitical tremor will repeat the pattern. Policymakers may swap cardboard files for cloud dashboards, but the outcome will rhyme: slow growth, fiscal strain, and political anger.

Because, in the end, you still can’t burn code.

The original article was authored by Thiemo Fetzer , a Professor of Economics at University Of Bonn, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled " Informational boundaries of the state and the energy crisis,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.