Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Europe’s inter‑generational statistics celebrate the pay cheque yet ignore the podium. By the second generation, immigrant men may earn almost what natives do, but the microphone in politics, media, or the haute fonction publique is still out of reach. Until the continent replaces lineage-based status tests with merit-based inclusion, convergence will remain superficial.

The comfort story everyone repeats

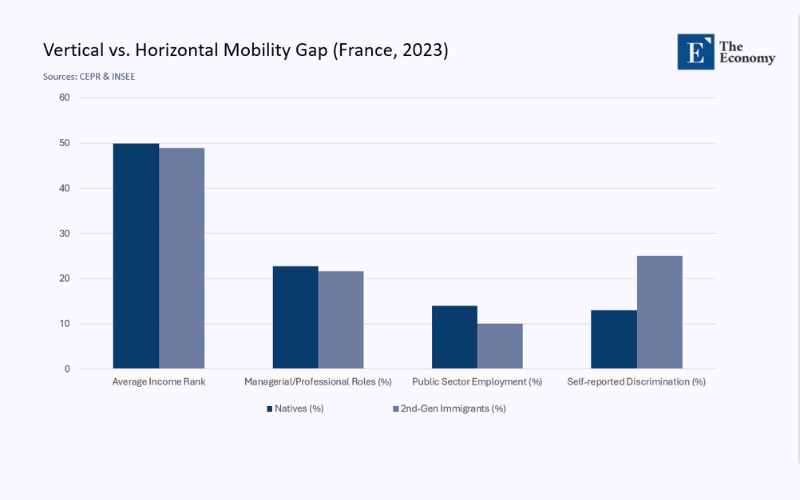

The new CEPR/VoxEU study combines matched parent–child files for 15 rich democracies and presents an uplifting headline. Across the sample, the median income rank gap narrows from 5 points in the first generation to barely 1 point in the second; sons trail by three points, while daughters are statistically equal to their native peers.On paper, the children of immigrants are almost “caught up”.

However, the paper’s dependent variable is a private number on a tax return, not the capacity to hold public power, or even to speak on behalf of the organisation in which one works. This discrepancy highlights the persistence of systemic barriers that prevent immigrant descendants from achieving true social mobility. The CV may convey a sense of integration, but the business card still signals a back-office feel, reinforcing the need for policy changes to ensure true inclusion.

Zoom in on France: mobility without momentum

Pascal Achard’s 2024 Journal of Public Economics article dismantles the comfort story when one examines lineage instead of cohort averages. Using the Trajectoires et Origines survey, he follows three generations of families that straddled the Mediterranean. Two facts matter:

- Occupational U‑shape – arrival downgrading erases pre‑migration status, but that hidden hierarchy resurfaces in the grandchildren. The heterogeneity that seemed to vanish in the first generation is merely buried, not broken.

- Grandparent grip – characteristics of immigrant grandparents are more predictive of their grandchildren’s education than the same traits among natives, a sign that lineage matters more for outsiders.

Achard’s elasticities are small but stubborn: for immigrant families, the shadow of origin‑country class outweighs destination‑country schooling. Translate this into the CEPR framework, and the rank gap looks less like a ladder climbed than a treadmill walked; an invisible headwind of status inheritance offsets every generational step forward.

The male penalty and the public‑facing void

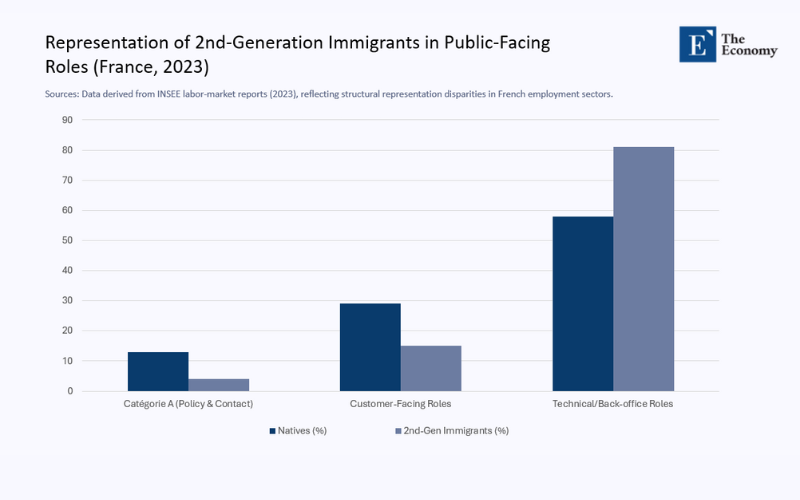

Aggregate French labour data confirm that the earnings catch‑up does not entail equal visibility. Among people in the workforce aged 15–64 in 2023, only 21.6% of immigrant descendants hold a managerial or professional post, compared to 22.7% of workers without a migration background. The numerical gap appears small until one considers that children of immigrants are, on average, better educated than natives from the same income decile. Put differently, equal professional status requires super‑normal credentials when your surname sounds foreign. This disparity is further exacerbated by what is often referred to as the 'male penalty'. Despite their higher education levels, second-generation men, in particular, face significant barriers to accessing public-facing roles, which are often reserved for native-born colleagues.

In the civil service, where job security and symbolic authority converge, the distance widens. Just 10% of descendants of immigrants are public-sector employees, compared with 14% of natives. first-generation immigrants languish at 6%. These shares include myriad back‑office roles. In the coveted catégorie A posts that involve policy design or direct citizen contact, second‑generation men remain outliers.

Why does the ladder break halfway

The table below summarizes the structural barriers that explain why second-generation immigrant men often stall in mid-level roles despite qualifications that match or exceed those of their native-born peers.

| Structural brake | Mechanism in practice |

| Credential devaluation | Foreign degrees – and sometimes French degrees held by “non‑native‑sounding” graduates – are viewed as lower‑signal quality, forcing the first generation into mismatched jobs and leaving sons without robust networks. |

| Segregated networks | Recruiters in politics, media, and high administration continue to fish in the pools of Grandes Écoles alums, who remain demographically narrow. |

| Statistical discrimination | Accent, address, and surname trigger heuristics about “fit” with client-facing roles, so hiring managers minimize perceived risk by keeping immigrant men in technical backrooms. |

| Citizenship lag | Naturalisation rules have loosened, but timing matters: late‑adolescence naturalisations miss the formative internship window when elite paths crystallise. |

| Geographic penalty | Immigrant families are concentrated in outer suburbs with weak transport ties to the internship‑rich centre, compounding opportunity costs. |

These frictions do not disappear when income rises; they mutate. The son of a plumber can become a public‑facing sales manager if his accent matches the market’s stereotype of professionalism. The son of a Tunisian engineer-turned-taxi driver may graduate from a business school and still be funnelled into a quiet analytics cubicle. Both earn similar euros; one commands symbolic capital.

Reading the numbers correctly: vertical ≠ and horizontal mobility

The CEPR team measures vertical movement – how high up the income ladder children climb relative to their parents. Achard and INSEE highlight the lack of horizontal mobility – the ability to secure positions of social recognition at the same level of income.

Vertical gaps are nearly closed; however, horizontal access and subjective belonging remain. For policy, celebrating the first metric while ignoring the second is akin to judging a marathon by split times but ignoring the finish line.

Policy: from tax records to tribunes

- Policy changes, such as publishing representation scorecards, can bring hope for a more inclusive future. Annual public reports should list the share of immigrant-origin staff in public-facing roles, such as court spokespersons, public broadcasters, and préfets. This transparency can nudge institutions to fix skewed leadership pipelines, paving the way for a more equitable society.

- Recognizing foreign‑earned and minority‑earned credentials through policy changes can bring optimism for the future. Fast-tracking equivalence for foreign degrees and auditing hiring panels for implicit discounting of suburban or overseas campuses can level the playing field. These changes can ensure that merit, not background, determines one's professional trajectory.

- Mentor‑and‑sponsor schemes inside ministries – Pair second‑generation professionals with senior civil servants who open network doors that merit alone cannot.

- Bias‑diagnostic recruitment – Blind CV screening, AI‑assisted accent anonymisation in first‑round interviews, and ex‑post audits linking applicant origins to outcomes.

- Grandparent SES tracking in surveys – As Achard shows, the starting point matters. Incorporating grandparent data into national panels helps target scholarships and apprenticeships precisely where the status headwind is strongest.

Arithmetic is not assimilation

When Brussels or Paris points to income convergence as proof of integration, it praises the symptom, not the cure. Western Europe still operates under an unspoken cultural clearance system, in which surnames, speech patterns, and inherited networks determine who represents the firm, the ministry, or the Republic. Income mobility reveals that immigrant families work – and overwork – the system; status rigidity demonstrates that the system still works against them. Unless policymakers learn to measure and reward horizontal integration – the ability to be visible, authoritative, and ordinary simultaneously – Europe will continue to produce graduates who write reports but never read them aloud. The glass ceiling may be higher than before, but it remains composed of the same unforgiving material.

The original article was authored by Leah Boustan, a Professor of Economics at Princeton, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Intergenerational mobility of immigrants in 15 destination countries," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.