Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

It's crucial to understand that when the cost of living is determined by factors such as the price of oil, rather than the price of money, the effectiveness of tighter money in extinguishing demand is limited. In the 2021‑24 period, the inflationary blaze was fueled by external factors, not by the reserves of central banks.

Elasticity and the Mirage of Control

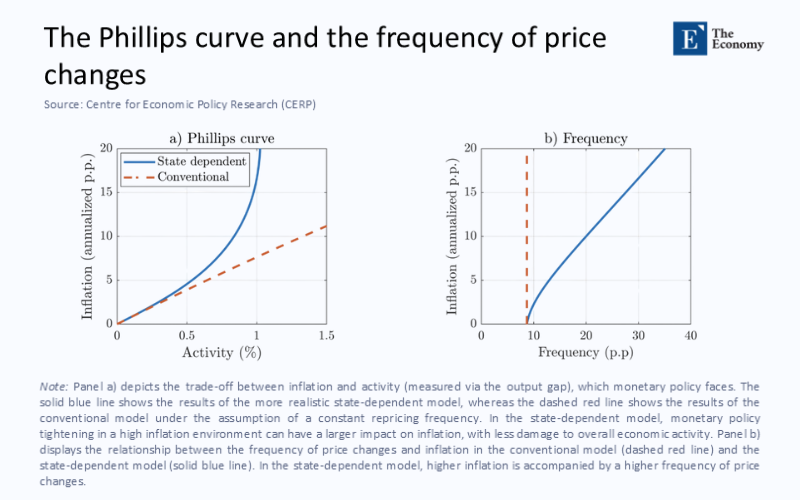

A striking conclusion in the most‑cited micro‑pricing papers of the past two years is that firms on both sides of the Atlantic shortened the time they kept a given sticker on the shelf. Super‑market scans in the euro area show the median duration between price changes collapsing from roughly eight months in 2015‑19 to about three and a half in 2022. U.S. convenience‑store data point to a similar halving of repricing intervals. Measured in menu‑cost models, that jump in frequency converts into a steeper Phillips curve and seems to vindicate the case for tighter policy. If prices adjust faster, the intuition goes, an interest‑rate jolt bites sooner, and the growth cost of disinflation shrinks.

Yet the convenience of the argument conceals a category error. Elasticity shows that prices can move; it says nothing about why they move. In the post‑COVID cycle, they moved largely because of cost‑push shocks, not because a burst of consumer or fiscal excess left demand overheating. When price flexibility merely accelerates the pass‑through of imported costs, the central bank gains speed on a road that still leads in the wrong direction. Raising the policy rate under those conditions turns into a game of Whac‑a‑Mole in which the mole is drilled into a foreign pipeline thousands of kilometres away.

Energy Shock Architecture and Monetary Limitations

The elasticity of price adjustments, particularly in sectors heavily dependent on global supply chains, determines how inflationary shocks spread. As shown in the Figure below, the Phillips Curve steepens dramatically when the frequency of price changes accelerates. This phenomenon was evident during the 2021–2024 inflation surge, as firms across the euro area and the United States shortened their repricing cycles from months to weeks. The acceleration reflects a more sensitive pass-through from cost-push shocks, reinforcing the argument that monetary policy alone is ill-suited to contain supply-driven inflation.

Monetary levers can influence spending and credit creation, but their impact on the geology, logistics, and geopolitics that determine the supply of hydrocarbons is indirect. In 2022, despite soaring prices, global crude demand was still below 2019 levels, highlighting the supply‑dominant nature of the spike. This underscores that central banks' tools have a far narrower impact on inflation than headline numbers might suggest.

An Empirical Scorecard Without the Crutch of Demand

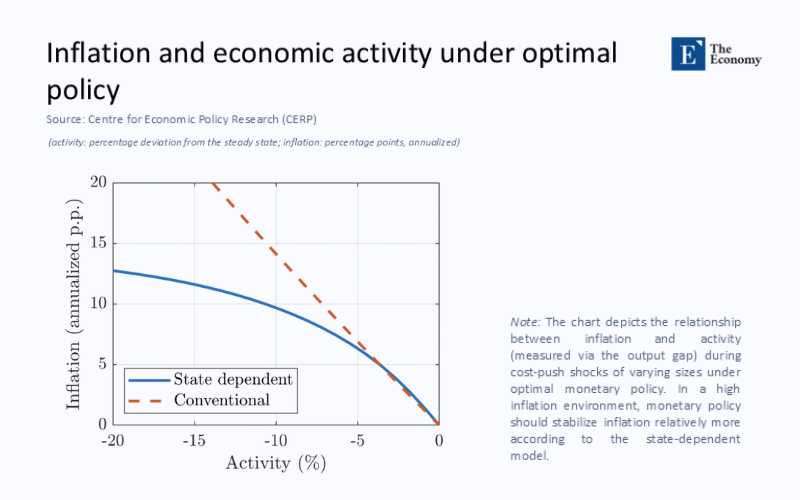

The relationship between inflation and economic output under optimal policy constraints is more nuanced than traditional models suggest. The Figure below shows that the optimal policy under state-dependent conditions allows for a much softer trade-off between inflation control and output reduction. The conventional model (dashed red line) predicts harsh output losses for modest inflation gains, whereas the state-dependent approach (solid blue line) shows a more efficient balance. This visual representation underscores the idea that when overly aggressive, monetary policy inflicts unnecessary economic damage without proportional disinflation.

The difference in these curves visually emphasizes the cost of monetary overreach. A state-dependent policy approach would have shielded more output without sacrificing inflation control, a principle that underpins modern adaptive policy frameworks.

How Tight Money Undermined Long‑Run Capacity

The opportunity cost of over‑tightening rarely features in quarterly press conferences, yet it significantly shapes the productivity frontier of the next decade. Three channels illustrate the long-term damage of such policies.

First, renewable energy investment stumbled precisely when Europe sought to escape fossil‑fuel dependency. Industry trackers estimate that onshore wind auctions in Germany and solar installation pipelines in Spain suffered combined cancellations and delays worth roughly sixty billion U.S. dollars between 2022 and 2024, much of it blamed on discount‑rate shocks as financing costs leapt with policy rates. Each gigawatt deferred prolongs reliance on imported natural gas and locks in the vulnerability that made inflation so severe.

Second, semiconductor capacity—the choke point behind the 2021 global goods spike—remained below the pre‑pandemic trend despite the U.S. CHIPS Act carrots. Rising hurdle rates pushed private co‑investment below original projections, eroding the strategic diversification the Act was meant to secure. Estimates published by the Dallas Fed suggest that every billion dollars of delayed fab spending subtracts non‑trivial fractions from potential output four to five years out.

Third, the housing channel became an ironic self‑inflicted wound. As thirty‑year mortgage rates punched through seven percent in the United States, residential starts collapsed to a six‑year low. The shelter component of CPI, heavily weighted and slow to reverse, overtook energy as the most significant contributor to core inflation in 2023, courtesy of the very monetary stance designed to curb inflation. Europe experienced a parallel squeeze, with German completions down double digits and French permits at a two‑decade trough.

Each strand of energy, chips, and housing illustrates a broader truth: monetary stringency can undermine the supply‑side capacity that central banks ultimately rely on to anchor prices. Policy sows the seeds of future rigidity by shrinking investment when the inflation shock is external.

Methodological Pitfalls of Elasticity‑Centric Models

The allure of the elasticity narrative rests on elegant models that treat the source of the shock as irrelevant. In a canonical sticky‑price framework, the frequency of price adjustment alone dictates how output and inflation respond to a policy impulse. But once an exogenous supply shock dominates, the model’s core assumption—that the central bank controls the primary driver of price levels—falters.

Researchers who embed an explicit energy‑input block into a New Keynesian environment find a starkly different optimum. Simulations in an October 2024 IMF paper show that a one‑standard‑deviation oil shock calls for a real‑rate increase of only 70 to 90 basis points to stabilize expectations, roughly one‑third of the hikes delivered in 2022‑23. A multi‑sector vector‑autoregression covering twenty advanced economies reaches a similar conclusion: supply shocks explained up to 60% of headline inflation variance during the episode, whereas monetary‑policy shocks accounted for less than 15%.

The lesson is not that central banks were powerless. Rather, their instruments were miscalibrated to the actual propagation mechanism. Precision, not aggression, should have been the guiding principle.

A Blueprint for Hybrid Policy

An alternative playbook would have combined calibrated monetary restraint with forceful supply‑side action. Moderately higher rates—sufficient to prevent a wage‑price spiral—would still have been necessary, but they could have been paired with strategic energy buffering and targeted fiscal insulation.

Coordinated releases from strategic petroleum reserves in spring 2022, totalling about 240 million barrels, did shave several dollars off crude futures, yet the initiative ended before supply was fully restored. Extending that effort while accelerating approvals for renewable projects and electrified freight corridors would have dampened the second‑round effects of energy without inflicting the broad demand contraction seen in 2023. Near‑shoring subsidies for critical inputs—lithium refinement, semiconductor packaging, medical‑grade glass—could have reduced logistics bottlenecks that elevated goods prices even as container rates fell.

Fiscal transfer design mattered as well. Countries such as France and Spain, which tied energy rebates to meter readings rather than offering blanket cash, shielded real incomes while keeping aggregate demand in check. Their consumption paths proved notably smoother than those of peers that relied solely on the interest‑rate channel, and their disinflation occurred with smaller output costs, as documented in recent Eurostat revisions.

None of these measures depends on the elasticity parameter. They address the root of price pressures rather than their velocity, turning the central question from “How fast do prices move?” to “What moves them in the first place?”

Toward Humility and Precision in Central Banking

The 2021‑24 inflation wave revealed a blind spot in the profession’s reflexes. A generation of policymakers trained to view inflation as a demand phenomenon reached instinctively for the interest‑rate lever. They found comfort in new price elasticity studies, reading faster repricing as evidence that their tool would strike with newfound speed. The experience that followed was more sobering. Disinflation arrived, but it arrived sluggishly and at a real cost. Headline relief stemmed at least as much from the gradual ebb of energy prices and the reopening of supply chains as from the effect of higher borrowing costs.

Going forward, a three‑step discipline is essential. First, diagnose the shock vector before prescribing a rate path. Second, coordinate monetary moves with nimble, targeted fiscal and industrial measures that can tame supply constraints directly. Third, real‑time sacrifice ratios are tracked, and the reverse course is taken when marginal output losses exceed marginal disinflation gains. In short, elasticity is a descriptive statistic, not a policy mandate.

The next inflation test may arise from climate disruptions, renewed geopolitical strife, or pandemics we cannot yet foresee. If central banks internalize the lessons of 2021‑24, they will treat interest rates as one tool among many rather than the solitary hammer in the kit. If they do not, we may again pay dearly to discover that beating demand does little when the spark lies in supply.

The original article was authored by Peter Karadi, a Senior Lead Economist at the European Central Bank, along with four co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Why monetary policy should crack down harder during high inflation,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.