Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

A significant shift is underway: while the dollar still serves as the global alarm bell, the hand that answers the call is no longer confined to Washington.

The Silent Arithmetic of Declining Dominance

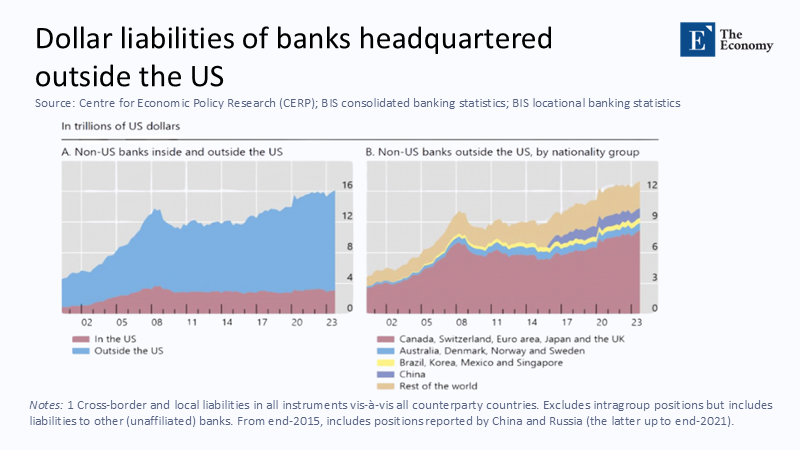

At first glance, nothing has changed. 90% of cross‑border trade invoices and almost every commodity contract are still denominated in dollars. Yet, the underlying stock of safe dollar assets is increasingly offshored. The figure below illustrates this shift: non-US banks headquartered outside the United States have steadily increased their dollar liabilities, growing even faster outside American borders. This redistribution of dollar risk highlights the underlying fragility the proposed coalition seeks to address, providing a broader buffer against liquidity crises.

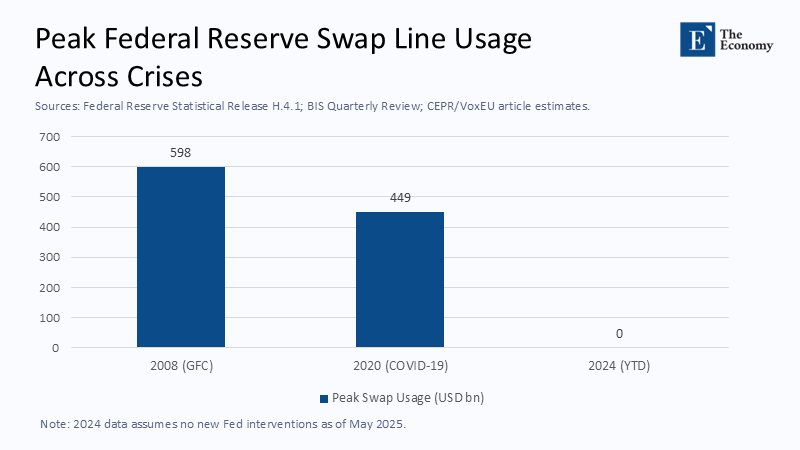

Numbers matter because they reveal capacity. Fourteen advanced and upper‑middle‑income central banks already control roughly $1.9 trillion in Treasuries and bills—more than triple the peak draw on Federal Reserve swaps during the 2008 panic and quadruple the Covid‑19 surge. That pool alone could refinance the entire stock of cross‑border commercial paper funding by non‑US banks for two quarters without touching Federal Reserve wires.

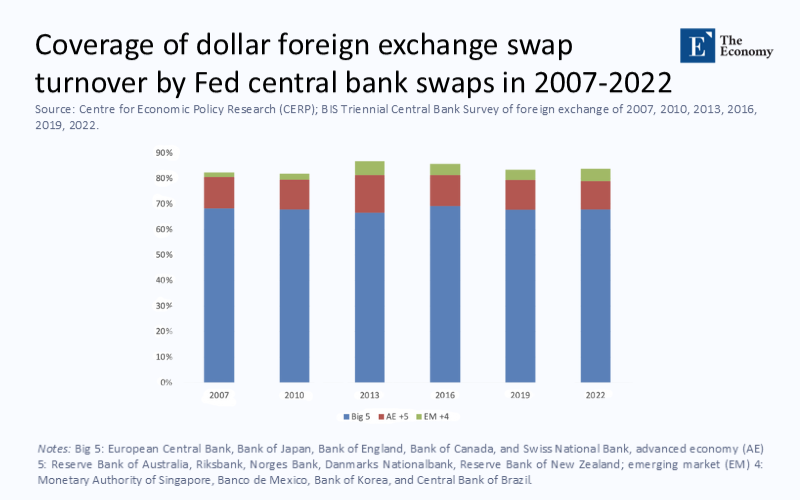

As shown in the Figure below, dollar foreign exchange swaps are heavily concentrated in just five central banks, covering over 80% of global swap turnover during crises. This concentrated exposure underscores the fragility of dollar liquidity under stress, which the proposed coalition seeks to diversify.

The distribution of swap lines reinforces the strategic vulnerability in dollar liquidity, concentrated in a handful of central banks, any disruption reverberates across the global financial system. The coalition’s design is aimed at decentralizing this risk and broadening liquidity access beyond the traditional Big 5.

Why Kindleberger’s Ghost Haunts 2025

Charles Kindleberger argued five decades ago that financial systems collapse when the incumbent hegemon refuses to act as a lender of last resort. The fear today is not that the United States cannot supply dollars, but that domestic politics may choose delay or denial. The 2023 debt‑ceiling standoff, which pushed one‑year credit‑default‑swap spreads on U.S. Treasuries above those on Belgium and Finland, was a foretaste. Markets digested the spectacle and priced it in; policymakers abroad took notes on how to insure against it.

Political uncertainty translates directly into funding costs. During the eight‑week debt‑ceiling impasse, the cross‑currency basis for three‑month dollar-yen swaps widened by 37 basis points, echoing patterns last observed in March 2020. The point is not that Congress will necessarily force a default; the fact is that the dollar’s liquidity premium now embeds a risk of coercion. Global banks and reserve managers are building a firewall because the probability is small, but the tail risk is fatal.

Unveiling a Coalition Backstop

The emerging proposal—first sketched by Choi, Eichengreen, and Simpson‑Bell—envisions a rules‑based pool of dollar securities parked with the Bank for International Settlements. Participants would pledge a slice of their reserve Treasuries as collateral; the BIS would tokenize those claims and stand ready to swap them for dollars with any member facing a shortage. The scheme is less revolutionary than it sounds: the BIS was founded in 1930 for precisely such cross‑border stabilization, and the institution already intermediates gold swaps for several G20 central banks.

What is new is scale and technology. In November 2024, the BIS Innovation Hub declared its Cambridge multi‑CBDC prototype an MVP, demonstrating two‑second cross‑border settlements among seven central banks on a permissioned ledger. Embedding a tokenised treasury repo inside mBridge would allow instant conversion of a Thai or Brazilian claim on a U.S. bill into settlement‑final dollars—no Fedwire, no FIMA window, no New York legal entity.

Governance would rest on pre‑agreed triggers. For instance, an automatic draw could activate if the three‑month FRA‑OIS spread breached 50 basis points for 48 hours or cross‑currency basis swaps widened beyond two standard deviations. Both signals captured funding stress during the Covid‑19 dash‑for‑cash and the Russia–Ukraine sanctions shock of March 2022.

Capacity Tested Against Real‑World Stress

Swap‑line history offers a yardstick. The bar chart above shows how outstanding balances peaked at $598 billion in December 2008, faded to near zero, and then surged to $449 billion in April 2020. Global offshore dollar liabilities doubled between those dates, from $8.7 trillion to $17.9 trillion. A $1.9 trillion reserve pool, even with a 30 % haircut for liquidity buffers, could thus cover four times the maximum historical draw. In practical terms, that is enough to refinance every non‑US bank maturing dollar repo for three months under stress.

A frequent counter is that only the Federal Reserve can create base money ex nihilo, whereas a pool depletes with use. True, but incomplete. In each historical episode, actual usage never approached the theoretical limit: the Fed’s 2008 swap authorization was $620 billion, of which $50 billion remained untapped at peak; in 2020, the ceiling was technically unlimited, yet drawdowns shrank to $12 billion within eight months. Liquidity crises are quenched by credible capacity more than actual disbursement—a visible trillion under joint control supplies that credibility, especially when the alternative is political suspense.

Geoeconomic Spillovers and Systemic Incentives

A multilateral backstop has distributional consequences. European banks account for 34 % of offshore dollar books but absorbed over 70 % of Fed swap draws in 2020. Japan, with the world’s most prominent net foreign assets position, accounted for another 11%. Concentration breeds moral hazard: why should Seoul or Ottawa socialise the dollar risk created by Frankfurt? The proposed remedy contributes to each member’s net offshore‑dollar liabilities, ensuring Spain or Sweden pays a proportion of its private sector’s exposure.

The scheme also shifts bargaining power inside the dollar system. A country that loses swap access faces a binary verdict from Washington. Under a pool model, that same country must convince a diverse committee, diluting U.S. leverage. Yet the dollar itself is not displaced. On day one, the coalition remains fully collateralised by treasuries, and the unit of account is unchanged. What changes is who can weaponise liquidity. In effect, multilateralism inoculates the currency against unilateral political veto.

The Fed’s Rational Self‑Interest

It seems paradoxical, but the Federal Reserve would win from credible substitutes. Every time global funding breaks, the Fed must flood domestic markets with reserves to stabilize foreign sentiment, often long after the shock has passed. That complicates its inflation and employment mandates. Offloading the role of global fire marshal would allow the FOMC to focus on U.S. dual goals, reducing the conflict between domestic and international stabilization.

Moreover, closing the FIMA repo window or refusing swaps would backfire. Foreign central banks would sell Treasuries to raise cash, driving repo rates higher and draining U.S. money‑market funds. A pre‑market mechanism that turns those Treasuries into dollar liquidity without sale protects the Fed’s transmission. Thus, the coalition scheme arguably completes the international dollar market rather than cannibalising it.

Beyond Liquidity—A Platform for Policy Convergence, Ensuring a Unified Approach to Global Financial Stability

A dollar‑security pool is also a laboratory for bigger innovations. Tokenised collateral opens the door to programmable policy—for example, linking draw amounts to sustainability metrics or digital KYC protocols. Over time, members could pool non‑dollar assets—bundled SDRs, renminbi bills, green bonds—creating a multilayered reserve asset that diversifies without fragmenting markets. That is not the plan’s first objective, but history shows that liquidity cooperation naturally leads to broader integration: the 1950 European Payments Union preceded the European Monetary System by three decades.

The Dollar After Hegemony

Power transitions are usually narrated in terms of currencies dethroning currencies: sterling to dollar, dollar to yuan. Reality is subtler. In 2025, the greenback will not be replaced; the jurisdiction that controls its emergency pump will be pluralised. Think of it as constitutional reform rather than regime change. The dollar keeps its network externalities—deep Treasury markets, rule‑of‑law courts, and unmatched derivatives liquidity. What shifts is the monopoly on discretion?

If Washington embraces the logic, it secures the dollar’s primacy at minimal cost. If it resists, the coalition will build redundancy anyway because the mathematics of reserves and the politics of trust already dictate it. Either way, the world is constructing a dollar fire department that can answer the phone without reciting U.S. talking points first.

The implicit bargain of Bretton Woods was that dollar liquidity would flow on demand in return for the rest of the world holding U.S. debt. When that bargain appears conditional, rational actors insure against the contingency. The insurance premium is now visible in balance sheets, in BIS prototypes and, perhaps most tellingly, in the quiet diplomatic energy behind a coalition willing to act.

The central insight is not that the United States is abdicating leadership but that leadership in a multipolar world requires shared wiring, not solitary power. The dollar’s future will depend less on who prints it and more on who can guarantee its circulation when it matters. On that metric, the firehouse at Constitution Avenue no longer operates alone, and the world may be safer for it.

The original article was authored by Robert N. McCauley, a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Global Development Policy Center at Boston University. The English version of the article, titled "Avoiding Kindleberger’s trap: A dollar coalition of the willing,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.