Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

A battlefield that changed currencies

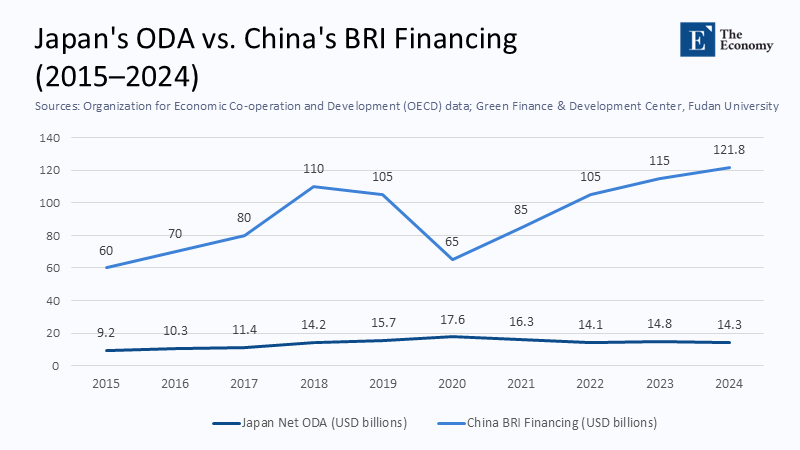

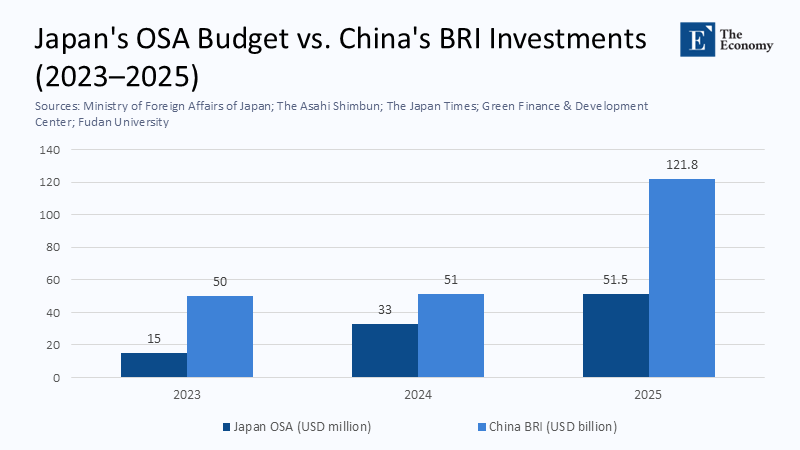

When the United States dismantled large sections of USAID during the 2023–25 federal downsizing, the Indo‑Pacific’s most reliable source of concessional finance vanished almost overnight. Washington’s drawdown removed roughly US$ $6 billion annually in bilateral economic assistance, pushing UN agencies into layoffs and programme closures from Bangladesh to the Solomon Islands. Europe, meanwhile, has been forced to redirect money it once reserved for global poverty reduction toward its re‑armament; defence budgets across the continent jumped 11.7% in real terms in 2024 alone, the sharpest annual surge since the end of the Cold War. The moment Washington and Brussels retreated, East Asian chequebooks stepped forward. China scaled its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a global development strategy involving infrastructure development and investments in nearly 70 countries, to a record US $121.8 billion worth of deals in 2024, including more than US $70 billion in construction contracts. Japan answered with a qualitatively different weapon: a fusion of classic Official Development Assistance (ODA) and the new, explicitly military‑tinted Official Security Assistance (OSA).

Tokyo’s dual‑track doctrine

Japan’s ODA may have plateaued in nominal terms—preliminary OECD data show net disbursements of about US $14 billion in 2024, still enough to keep Tokyo in the DAC top five—but the defence adjunct to that civilian aid is expanding at an extraordinary rate. The Ministry of Defence has asked the Diet for ¥8.1 billion in FY 2025 to fund OSA, a 60% leap over the current fiscal year and enough to double the roster of eligible recipients. This expansion, coupled with the strategic foresight of Tokyo, is a testament to Japan's commitment to the region's stability. OSA shipments include coastal surveillance radar to the Philippines, rigid‑hulled inflatable boats for maritime interdiction, and a long‑range air‑defence radar package for Mongolia’s air force. The critical design element is interoperability: Tokyo multiplies its strategic value by ensuring that donated systems can plug directly into US and Australian command networks without raising absolute spending to Chinese levels.

Scale versus precision: reading the ledger

The visual comparison above underscores a structural asymmetry that is unlikely to disappear. Even if Tokyo were to fulfil every item on its current development docket, Japan’s annual net aid outlay would remain barely one‑eighth of Beijing’s BRI investment and construction portfolio. However, the numbers conceal divergent business models. Japan continues to deliver loans with grant elements approaching 45% for lower‑middle‑income Asian borrowers, according to recent JICA data. In contrast, China Exim Bank’s average grant element now hovers around 26%. That difference translates directly into debt‑service obligations: Philippine Treasury models show that a US $500 million Japanese concessional loan amortises at roughly half the annual cost of an equivalently sized Chinese credit line once grace periods expire.

The debt‑sustainability dividend became stark in Sri Lanka’s 2025 restructuring talks. Colombo secured a US $2.5 billion reschedule from Japan on highly concessional terms—maturities stretching to 2042 and a near‑zero interest period—while negotiations with Chinese creditors dragged on without comparable relief. This cautionary tale underscores the weight of the decisions made by Southeast Asian finance ministries. Such contrasts reinforce the perception among these ministries that Japanese money, though less plentiful, is the safer bet when the public backlash against “debt‑trap” outcomes looms.

When concrete becomes an early‑warning system

Tokyo’s assistance purposely blurs civilian and military categories. The ostensibly commercial upgrade of Subic Bay’s container wharves includes quay reinforcement to accommodate amphibious‑ready groups. A Japanese‑financed air traffic management overhaul on Palawan Island provides dual‑use radar feeds, which are radar systems that can be used for both civilian air traffic control and military surveillance, that the Philippine Air Force can splice into its maritime‑domain awareness grid. These design nuances convert ordinary infrastructure into force multipliers—assets that can extend sensors to reach hundreds of kilometres into contested waters with no Japanese soldier in sight. Civilian ministries sign the loan papers; defence planners reap the deterrent value.

Beijing practises a similar blend, though on a larger canvas. The Laos–China Railway, which cut transit time from Kunming to Vientiane in half, is chiefly portrayed as a trade corridor yet offers a logistics artery that could carry PLA matériel toward the Gulf of Thailand in a crisis. The Ream naval expansion in Cambodia, financed under opaque grant–loan hybrids, affords China its first potential blue‑water pit‑stop on mainland Southeast Asia. This prospect alarms Vietnamese strategists far more than the shipyards’ published tonnage figures. Aid projects now embed latent military options as a matter of routine.

The narrative war: memory against the environment

China’s counter‑narrative leans heavily on wartime memory, depicting Japan’s OSA as the digital-age echo of Imperial occupation. That trope resonates among older Malaysians and Indonesians but competes with the lived experience of BRI environmental missteps. Indonesian civil society groups blame recurring blackouts in West Java on reliability failures at BRI coal plants, and fishing communities upriver of Chinese‑built dams in Laos continue to document ecological harm. The 2024 ISEAS survey captures the resulting ambivalence: trust in Chinese economic leadership among ASEAN elites slid from 54% in 2019 to 38 % in 2024, whereas confidence in Japan remained at 61 %. In other words, Tokyo’s greatest reputational asset is not money but predictability.

Europe’s enforced retreat

The redirection of European budgets toward armour and ammunition has added another layer to the contest. The EU’s flagship Global Gateway funds were slashed by almost one‑third in the 2025–27 multi‑annual financial framework, according to internal Commission spending tables seen by Brussels‑based think tanks; the savings are being channelled into a new European Defence Production Act that subsidises missile manufacture. Although European firms remain major subcontractors in Asian projects—French tunnelling companies bore out portions of the Jakarta metro, German engineering giants supply turbines for Vietnamese wind farms—the EU, as a concessional financier, is receding. Where Europe once balanced Asian alignment choices, its fiscal pivot now leaves ASEAN capitals with a binary option: Beijing’s scale or Tokyo’s standards.

Quantifying leverage: the security coefficients of aid

A simple ratio illuminates the leverage differential. Take the Philippines, which received about US $750 million in net Japanese disbursements between 2021 and 2024 and roughly US $2 billion in new Chinese finance over the same period. Yet Manila’s Department of National Defense values Japan’s coastal radar donation, valued at just US$ 22 million, at almost three times the strategic worth of China’s multimillion‑dollar Chico River Pump Irrigation Project. This stark contrast in strategic value underscores the impact of Tokyo's aid on the recipient's security posture. Measuring only cash misreads power; what matters is how effectively a dollar of aid alters the recipient’s security posture.

We can derive an indicative “security coefficient” by dividing the military utility (proxied by deterrence days per year a system contributes) by the loan principal. If the Palawan radar extension provides 365 days of early‑warning coverage and costs US $22 million, its coefficient is roughly 16.6. A Chinese‑funded expressway that modestly improves logistics during peacetime but could be cratered in the first hours of conflict may offer, at best, a coefficient of 0.5. Tokyo, in effect, purchases more usable influence per yen than Beijing per yuan.

Beijing’s strategic recalibration

Faced with this qualitative gap, Beijing moved in mid‑2024 to sweeten loan terms for digital infrastructure under US $150 million and authorised a 15% expansion of annual sovereign‑lending quotas. More importantly, the People’s Liberation Army began embedding training detachments in civilian projects—engineers at a Cambodian port expansion and cyber‑security technicians attached to Laos’s fibre‑optic backbone—effectively entwining defence cooperation with infrastructure delivery. The innovation trades cash for presence: every BRI digital node staffed by PLA‑linked contractors shifts local threat perceptions, regardless of loan amortisation schedules.

China is also learning from Japan’s victory in the environmental narrative. The National Development and Reform Commission unveiled new “Green BRI” guidelines in March 2025 that cap the emissions profile of overseas coal projects and raise due diligence hurdles for hydropower schemes in ecologically sensitive basins. Whether those guidelines produce material change remains uncertain, but the announcement shows that Beijing now concedes reputational ground to Tokyo on standards and sustainability.

The recipients’ calculus: autonomy through diversification

Smaller Indo‑Pacific economies recognise that the aid duel can underwrite or entrap autonomy. Cambodia leveraged Japanese interest in an alternative deep‑sea port to slash interest on a Chinese facility by 80 basis points. Conversely, Fiji almost lost a ¥12 billion Japanese climate‑resilience grant when it hesitated to pass labour‑law reforms; Beijing stepped in with untied finance, and Suva had to juggle parliamentary factions for fear of alienating either donor. Finance ministry spreadsheets in Jakarta and Bangkok now include an explicit “political conditionality” discount when comparing Japanese and Chinese offers: Japan’s conditions are predictable but policy‑heavy, China’s more opaque yet quick.

Forward trajectories: Can the contest stay healthy?

A managed competition that drives down borrowing costs while avoiding coercive dependence requires at least two stabilisers. First, Japan will need to mobilise private‑sector co‑investment to keep pace: blended‑finance vehicles that use ODA credit guarantees could stretch limited fiscal space without breaching Tokyo’s debt ceiling. Second, China must bring greater transparency to BRI term sheets; publishing uniform lending data would dispel the impression of debt‑trap diplomacy and reduce resistance generated by Ham‑bantota‑style leasebacks. The alternative is escalating secrecy, forcing ASEAN borrowers into zero‑sum choices.

At present, the signals are mixed. Japan’s Cabinet has already endorsed an 8.7‑trillion‑yen national defence budget for 2025, and discussions are underway about shifting production lines at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries toward dual‑use export capacity, hinting that OSA could grow even faster than today’s budget request suggests. China’s policy banks, for their part, are piloting a tranche of interest‑free digital‑connectivity loans—small by BRI standards but potentially brand‑polishing. If both initiatives mature, the aid race may evolve from a simple sum of money to a contest in governance templates.

Deterrence by chequebook

The Indo‑Pacific’s development‑finance arena has become a sophisticated form of power projection in which yen and yuan are substituted for frigates and fighter wings. With U.S. and European coffers turned inward, Tokyo now wields a disproportionate voice in setting the region’s strategic agenda because its money arrives encoded with interoperability, transparency, and environmental safeguards. Beijing counters with volume and a growing aptitude for narrative warfare, betting that sheer scale plus selective concessions can offset Japan’s qualitative edge. For recipient states, sovereignty in the next decade will depend less on which patron they choose than on how cleverly they pit one against the other, extracting infrastructure, training, and relief while avoiding the tightening strings of dependence.

The ledger has become the new order of battle, and every line item—be it a radar dome, a concessional loan, or a climate‑resilience grant—now carries geopolitical consequence.

The original article was authored by Sadia Rahman, a Lecturer at the Department of International and Strategic Studies at Universiti Malaya. The English version, titled "China’s economic pivot invites global recalibration," was published by East Asia Forum.