Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

Japan’s checkbook diplomacy, a testament to strategic foresight, has emerged as the region’s most precise political instrument. This is particularly significant as Washington retreats from large‑scale poverty‑reduction programs and Europe diverts development funds to its defense. What may seem like a technocratic surge in yen loans on the surface is actually a deliberate strategy to counterbalance Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). A decade ago, Chinese infrastructure finance seemed unstoppable; by 2025, Japanese official development assistance (ODA) has become the most agile lever of influence south of the Tropic of Cancer. The contest is no longer about who spends the most but who can embed their preferred rules in every kilometer of rail, fiber-optic cable, and patrol boat hull.

The Geopolitics of Checkbook Statecraft

Japan’s strategic shift in aid focus, as reflected in the 2023 revision of the Development Cooperation Charter, is a significant geopolitical move. The declaration that development cooperation is 'essential for the realization of a Free and Open Indo‑Pacific' transforms what was once seen as philanthropy into a form of hard‑edged statecraft. The numbers further underscore this shift. With net Japanese ODA reaching approximately US $17 billion in 2024, Tokyo has directed nearly half of its new commitments to maritime Southeast Asia and the Pacific, compared to just over a quarter a decade earlier. Moreover, Tokyo's pledge to mobilize over US $75 billion in public‑private infrastructure finance by 2030 formalizes an Indo‑Pacific‑first doctrine, treating development budgets as strategic artillery.

Beijing’s counter‑move remains the BRI. Yet the Chinese initiative, once expansive, is increasingly weighed down by its success. Between 2008 and 2021, “rescue lending”—short‑term bail‑outs offered to refinance maturing debts—reached about US $240 billion, dwarfing green‑field commitments. The newer loans do little more than prevent existing projects from defaulting, leaving less capital for new ports, power lines, or rail corridors. In other words, China is now paying to defend the empire it built yesterday rather than creating a larger one for tomorrow.

Western Retrenchment Creates a Strategic Vacuum

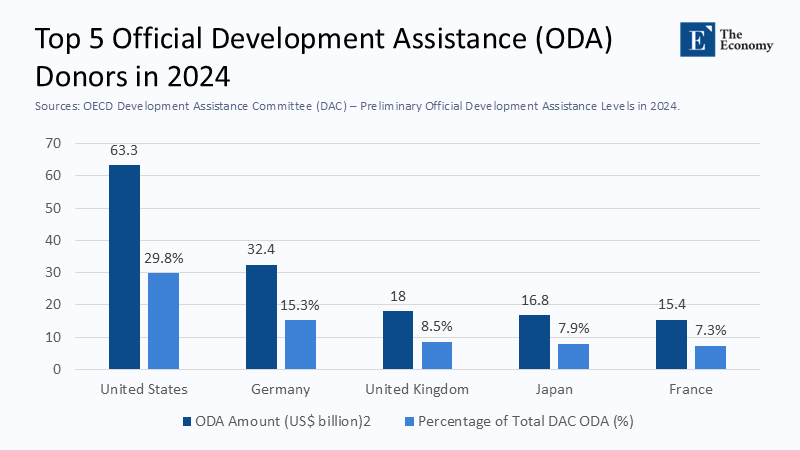

Japan has been able to step forward because traditional donors have been stepping back. In the United States, successive rescission proposals threaten to claw billions of dollars out of USAID’s unobligated balances over the next two fiscal years. Even when Washington re‑labels security or climate lines as development, the headline appropriation for classic poverty‑alleviation work is shrinking. Europe tells a similar story. Brussels has diverted a rising share of its external‑action budget to reinforce Ukraine, while defense spending across the continent now overshoots NATO’s 2 percent benchmark in a dozen member states. As a result, the EU’s programmable grants to Asia fell below US $3 billion in 2024, the lowest level since 2015.

The combined contraction of Western aid removes at least US $5 billion per year from Southeast Asia's aid marketplace. Japan has stepped in to fill roughly one-third of that gap, making its assistance the largest outside money on offer and the fastest growing. Japan's significant role in the region's aid landscape underscores its increasing influence and the strategic vacuum created by the retrenchment of traditional donors.

Speed, Conditionality and Multipliers: Japan’s Three Advantages

Japan’s rise in the aid landscape is underpinned by three strategic design choices that give its aid more traction. These choices, which include speed, conditionality, and the multiplier effect, have significantly enhanced the effectiveness of Japan's aid strategy, making its dollars more impactful and influential in the region.

The first advantage is speed. After streamlining safeguard procedures in 2023, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) now takes about fourteen months to convert a project from a concept note to a signed loan in Southeast Asia. A decade ago, the same process often consumed two full years. China, ironically, has slowed down. Policy‑bank risk manuals leaked in 2024 show new layers of due diligence added after high‑profile restructurings in Laos and Pakistan. When ministries in Jakarta or Manila complain about paperwork today, they describe JICA forms as “burdensome but predictable”; the Chinese forms, they say, have become “fast but opaque.” Predictability wins out when treasuries are wary of hidden penalties.

The second advantage is legally embedded conditionality. The 2023 Development Cooperation Charter links ODA to “the rule of law at sea.” This wording allows Japan to finance coastal radar chains, information‑fusion centers, and cybersecurity infrastructure while maintaining the civilian veneer essential to pacifist domestic politics. The same veneer will enable recipients to upgrade deterrence capabilities without triggering accusations of militarisation at home. China, by contrast, still presents dual‑use ports and pipelines as commercial endeavors, which provokes suspicion precisely because the line between commerce and coercion is never spelled out.

The third element is the multiplier effect. Japan almost always co-financed with the Asian Development Bank, the International Finance Corporation, or donor agencies from Australia and Europe. Therefore, a US $300 million yen loan can anchor a US $1 billion package. Chinese loans rarely syndicate; Beijing prefers one‑on‑one negotiations that maximize leverage but forgo the credibility that multilateral scrutiny confers.

Domestic Headwinds in Beijing and Tokyo

Even the most meticulously designed checkbook strategy depends on domestic fiscal headroom. Here, China finds itself constrained. Household spending finally nudged above 39 percent of GDP in 2023, but that figure still sits more than twenty percentage points below the global mean. Per‑capita consumption grew just over five percent in real terms last year, hardly enough to power the economy if exports falter. US tariffs averaging twenty‑five percent have stalled direct shipments to America, rerouting through Southeast Asia cushions but cannot replace a US $575 billion bilateral flow recorded in 2017. The slowdown shows up in consumer‑electronics demand: iPhone deliveries fell nine percent yearly in the first quarter of 2025, the seventh straight quarterly drop. Weak premium‑goods sales erode Beijing’s tax base and shrink the pot of subsidized credit once deployed abroad.

Japan’s challenges are different. Its population shrinks and ages, domestic growth barely touches one percent, and social security liabilities mount. Yet Japanese aid is self-financing mainly because more than four‑fifths of Southeast‑Asian allocations come as concessional loans with interest rates well below one percent. Repayments are recycled into new loans, creating a revolving fund that can survive even sluggish GDP growth at home.

Local Agency and the Politics of Memory

Southeast Asian leaders have learned to use rivalry to their advantage. The region’s collective memory oscillates between two metaphors—Japan’s wartime occupation and China’s centuries‑old tribute system—but present‑day elites actively use those memories as negotiating chips.

After cost overruns, Jakarta renegotiated Beijing’s interest‑rate spread on the Jakarta–Bandung high‑speed railway and promptly invited JICA to audit the proposed extension to Surabaya. The move turned a previously exclusive Sino‑Indonesian project into a triangular arrangement that forces each financier to offer better terms to stay in the game. Manila has accepted Japanese funding for a radar chain in Palawan even while it takes Chinese loans for a flood‑control dam in Mindanao; public opinion polls show broad support for diversified partnerships that keep any single creditor from dominating. Hanoi’s socioeconomic plan for 2024‑28 lists Japanese patrol vessels under the heading “infrastructure for the maritime economy,” thereby framing security hardware as a development deliverable.

Measuring the Battlefield of Dollars

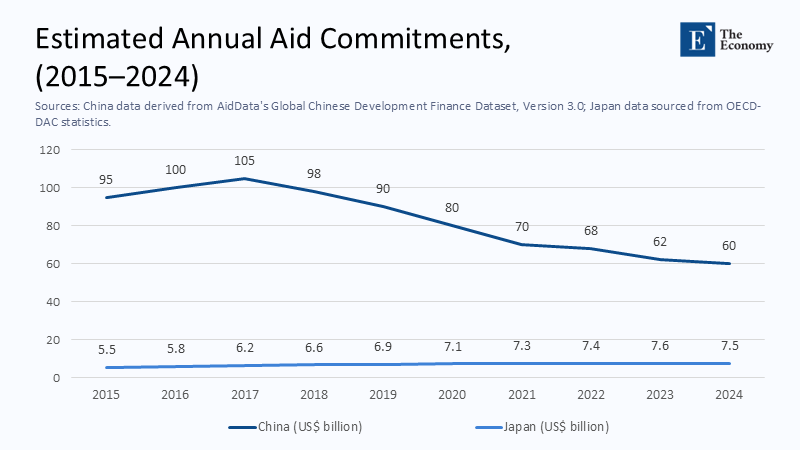

A snapshot of financial flows captures the shifting balance. Chinese commitments to the Indo‑Pacific have fallen from an estimated US $105 billion in 2017 to roughly US $60 billion last year. Japanese obligations, by contrast, have inched upward toward the US $7.5 billion mark and show no sign of retreat. On paper, China still outspends Japan eight to one. Yet the raw ratio hides two crucial facts. Almost half of Beijing’s current expenditures are used to refinance old debts, and a significant portion is priced above international lending benchmarks. Tokyo’s money, mostly concessional and often blended with multilateral equity, lands with greater developmental impact per dollar and fewer surprises in the fine print.

Even more telling is the gap’s trajectory. A decade ago, China’s Indo‑Pacific commitments exceeded Japan’s by a factor of twenty; the ratio now hovers around eight. Analysts projecting current trends see it shrinking to six by 2027 if Chinese rescue lending continues to cannibalize fresh credits and Japan maintains its steady pipeline.

Rules First: How Recipients Can Shape the Outcome

The emerging two‑track order, where Japanese speed meets Chinese scale, could benefit the Indo‑Pacific if recipient governments embed transparent rules that bind both donors. A harmonized ASEAN debt‑sustainability framework would be a start, obliging Tokyo and Beijing to present projects with comparable risk metrics. Competitive tendering requirements for major contracts, irrespective of financier, would erode the advantage tied to aid confers and reinforce value for money. Middle‑power donors—Australia, Korea, and India—could extend the multiplier principle by syndicating with Japan, reducing dependency on any single donor while leveraging Japanese concessional cash. Finally, reviving the stalled G20 discussion on multilateral workouts for BRI debt would pre‑empt the domino effect of ad‑hoc bilateral restructurings that sap growth and entangle politics.

The Indo‑Pacific is now a marketplace where governments can solicit offers, play suitors against one another, and select the financing terms best aligned with national development plans. A hundred years after colonial extraction and fifty years after Cold War patronage, Southeast Asia finds itself in a historically rare position: neither a chessboard on which great powers maneuver nor a distant frontier of someone else’s security perimeter, but an arena where local agency decides whether foreign money builds infrastructure or mortgages the future.

The original article was authored by Hiroaki Shiga, a Professor at the Graduate School of International Social Sciences. The English version, titled "Japan’s soft power gains a hard edge," was published by East Asia Forum.