Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

A fiscal jolt, a sudden and significant increase in financial aid, that doubled as public‑health policy

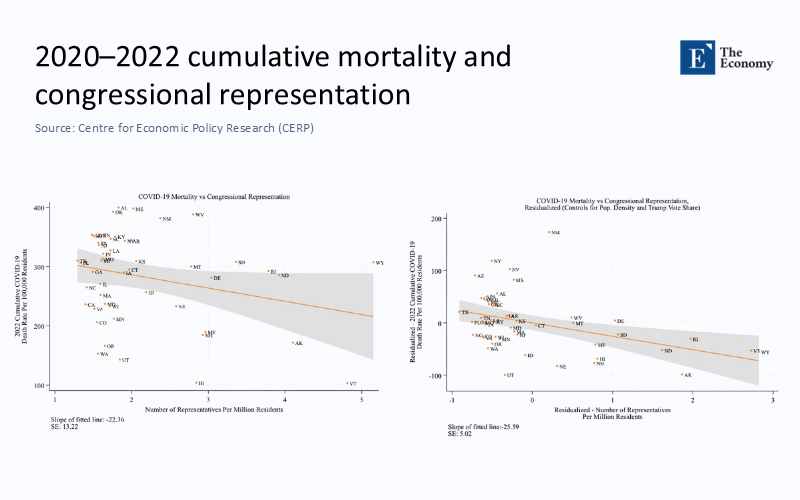

For all the ink spilled about trillion‑dollar rescue packages, one image captures their hidden dividend more crisply than any press release. Figure 1 in Clemens and Mahajan’s recent VoxEU column plots each US state’s congressional over‑representation on the horizontal axis and its cumulative COVID‑19 death rate, the total number of deaths over a period of time, on the vertical axis. The downward line is unmistakable: states that, for constitutional reasons, received about US$ $1,000 more per resident in federal transfers recorded twenty‑six fewer virus deaths per 100,000 people between 2020 and 2022.

The slope steepens after adjusting for density and partisan leanings, leaving little doubt that the money itself—and not an accident of demography—bought lives. Nothing about that transfer was designed as a health intervention, yet the chart exposes it as one.

Timing, not just totals, decided the payoff.

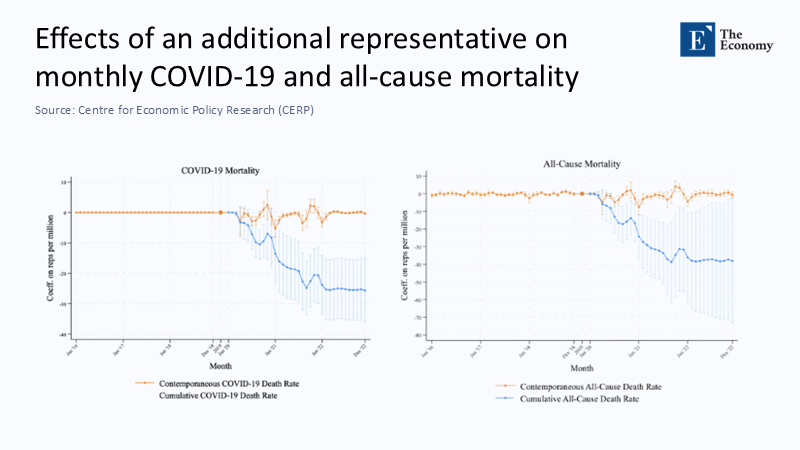

Flip to Figure 2 in the same study, and the mechanism comes into focus. The event‑study bars hover near zero through the first pandemic winter, then plunge just as mass vaccination begins in January 2021. By December 2022, the cumulative gap reached thirty‑eight avoided deaths per 100,000 once other causes are counted.

That time profile matters: Aid that arrived before clinics were ready to fill syringes bought hospitals enough breathing space to blunt the second winter wave. If the money had been delayed by a quarter, much of the mortality dividend would have vanished.

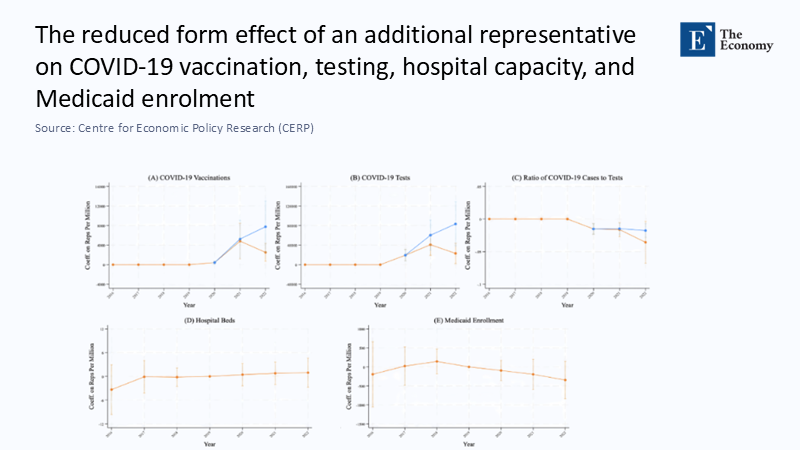

Figure 3 completes the forensic trio. Federal dollars explain a jump of eight to ten percentage points in testing intensity and roughly four points in complete vaccination, while measures of hospital‑bed capacity barely budge.

The real public good, it turns out, was information—tests that revealed where contagion lurked and vaccines that re‑priced personal risk. In other words, most health returns flowed through data and prevention, not bricks and mortar. This underscores the crucial role of data and information in shaping effective pandemic responses, empowering decision-makers to make informed choices.

The global ledger tells a different story—until you correct the numbers.

Yet juxtapose those U.S. charts with global cross‑country audits, and a paradox leaps off the page. By mid‑2020, rich countries housed only fifteen percent of humanity but reported almost four‑fifths of all confirmed COVID‑19 deaths. Developing nations, home to the remaining eighty‑five percent of people, accounted for barely one death in five. If fiscal power saved American lives, why did the largest treasuries preside over the most significant official body counts?

The answer begins with a statistical sleight of hand. Death, like any bureaucratic fact, must be certified. Where registries and testing falter, coffins slip through the spreadsheet. Official mortality counts, primarily driven by the strength of civil registration systems, skew toward countries that can accurately track deaths. In poorer nations, the infrastructure to certify and register deaths—especially in rural or conflict‑affected areas—is often weak or nonexistent.

The World Health Organization’s excess‑mortality model, released in May 2022, stripped away that disguise. It estimated 14.9 million pandemic deaths for 2020‑2021, nearly 2.8 times the official global tally. More tellingly, it located eighty‑one percent of the “missing” fatalities in middle‑income countries, not the wealthy bloc. These adjusted figures suggest the pandemic’s reach into poorer populations was far deeper than captured initially. While the more prosperous nations still bore a considerable share of the recorded fatalities, the apparent gap between high‑income and low‑income regions narrowed dramatically once the undercount was priced in.

Cash without capacity is a blunt instrument.

If under‑counting explains the paradox, institutional strength explains the residual. A Nature study published two weeks ago applied Bayesian Model Averaging to the WHO dataset and found that rule‑of‑law scores outranked GDP per capita as predictors of excess‑death variation. Fiscal scale mattered, but only where governance could channel money into traceable actions—exactly the condition satisfied in the Clemens‑Mahajan experiment. This highlights the critical role of effective governance in shaping health outcomes, underscoring the need for strong and transparent governance structures.

The International Monetary Fund’s Fiscal Monitor puts the fiscal split in raw relief: by April 2021, governments had deployed US$ $16 trillion in discretionary support, ninety per cent of it from advanced economies. That translated into about US$ $5,400 per resident in rich countries versus less than US$ $100 in low‑income nations, a vast and unsurprising chasm. The cost per excess death is more revealing once the WHO revision is applied. High‑income economies spent roughly US$ $5.7 million for every excess death on their soil, while lower‑middle‑income countries spent a fifteenth. The implication is not that the South was thrifty but that the North burned cash on margins where diminishing returns had already set in.

The quiet hero of every successful response: the ledger

Return to Figure 3 in the US study, and its understated lesson becomes universal. Tests and vaccinations worked because somebody logged them; mortality fell because somebody was counting. The same logic emerges from Our World in Data’s inventory of vital‑registration completeness: fewer than one in ten low‑income countries captures even eighty per cent of deaths in a timely, coded fashion. Without that backbone, stimulus checks have nowhere anatomically sound to land.

Toward a doctrine of “minimum viable preparedness”

The charts point to a straightforward, if uncomfortable, conclusion: finance information first. For less than one‑fifth of one per cent of G20 GDP, a multilateral fund could underwrite civil‑registration upgrades and genomic‑surveillance labs in every low‑ and lower‑middle‑income country. Vaccines and ventilators would still matter, but they would arrive in systems that track their success or failure in real time.

Second, tie health aid to verifiable milestones. The US state‑level results show that even politically distorted transfers reduce deaths when documentation is automatic. A global analogue would disperse money in tranches conditional on weekly excess‑mortality disclosure or real‑time vaccine stock‑flow reconciliation. This underscores the importance of transparency in health aid, highlighting the need for accountability in distributing and using funds. Conditionality, long a dirty word in development finance, becomes a life‑saving tool when its object is transparency rather than austerity.

Finally, rich‑country rescue bills should be redesigned for speed and specificity. Less than a dime of every federal dollar in the United States financed the test‑and‑vaccine axis that did the real work. The following emergency appropriation could earmark half its envelope for ring‑fenced accounts—mobile testing, cold‑chain logistics, data dashboards—payable within days of enactment. Figure 2’s time path shows that every month’s delay in early 2021 exacted thousands of avoidable deaths; no line item in any future budget will repurchase those months.

Why do we keep misreading the rich‑poor death gap?

Even with excess‑death corrections, lower‑income regions still appear to have weathered the virus marginally better than the wealthy. Demography offers part of the explanation; the median age in low‑income countries hovers around twenty‑seven, compared with forty‑one in high‑income countries, and infection‑fatality risk climbs exponentially. But age is not destiny. Mobility data from Google telemetry reveal that a ten‑point decline in workplace presence cut weekly case growth three times more in formal‑economy settings than in informal ones. Where lockdown compliance is economically impossible, the epidemiological payoff shrinks. Fiscal room to compensate informal earners was tiny in the South, further eroding the mortality benefits of mobility curbs. The circle closes: cash buys compliance only when institutions can deliver it quickly and credibly.

Counting as the first dose of every future vaccine

Strip away the national flags and the three headline charts from the US study draft, and you have a universal playbook. They declare that money matters most when it purchases information—tests that illuminate invisible outbreaks, registries that turn deaths into data, and dashboards that tell vaccinators where to go next. They also warn that the richest treasury will squander billions if it cannot see what the virus is doing—the global mortality map rewards not the deepest pockets but the clearest ledgers.

When historians write the balance sheet of COVID‑19, they will note that some nations bought time for science and spent it wisely, while others bought the same time and mislaid the receipt. The difference was not simply the checkbook size; it was whether the numbers at the bottom of those cheques reappeared, audited and traceable, in a public‑health ledger. Until every country can keep such a ledger, fiscal solidarity will write generous but partly invisible epitaphs.

The original article was authored by Jeffrey Clemens and Anwita Mahajan. The English version of the article, titled "The effects of fiscal aid on health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.