Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

The arrival of the first two‑tonne pallet of South Korean rice at Tokyo’s Odaiba wharf on 22 April may have seemed physically trivial. However, it carried the weight of a cultural earthquake, serving as undeniable evidence that Japan, a nation with a deep-rooted pride in its rice, could no longer sustain itself without external assistance.

Pride Meets Paradox

Japanese farm policy was designed to make that scene impossible for half a century. Import tariffs above 700 percent shielded growers, and glossy advertising elevated Koshihikari to an emblem of national identity. By spring 2025, retail prices still pierced that protective wall, soaring past ¥4,200 for a five‑kilogram bag—double the year‑earlier level—and supermarkets in Akita and Saitama erected ration signs that had not been seen since the 1993 Heisei shortage. The crack in the edifice was not a single bad harvest; it was the sum of misread numbers—on climate, acreage, labour, logistics, and, above all, tourism—that Tokyo’s planners treated as rounding errors until they converged into a million‑tonne gap.

The Shrinking Paddies

Could you start with the land itself? In 2022, the planted area for table rice fell to 1.251 million hectares, the smallest since records began, after decades of the acreage‑reduction scheme known as gentan kept production artificially tight. Although the scheme was officially scrapped in 2018, prefectural quotas and the political heft of the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives (JA) kept de facto controls in place. If acreage had merely held at its 2000 footprint of about 1.6 million hectares, Japan would harvest roughly 1.8 million additional tonnes today—enough to wipe out the current deficit several times over. The demographic overlay is brutal: the average rice farmer is sixty‑nine, and retirements now outpace new entrants five‑to‑one. Fields left fallow are often switched to feed rice or corn, crops that are insulated from consumer anger but irrelevant to the national diet.

Heat, Typhoons, and Yield Volatility

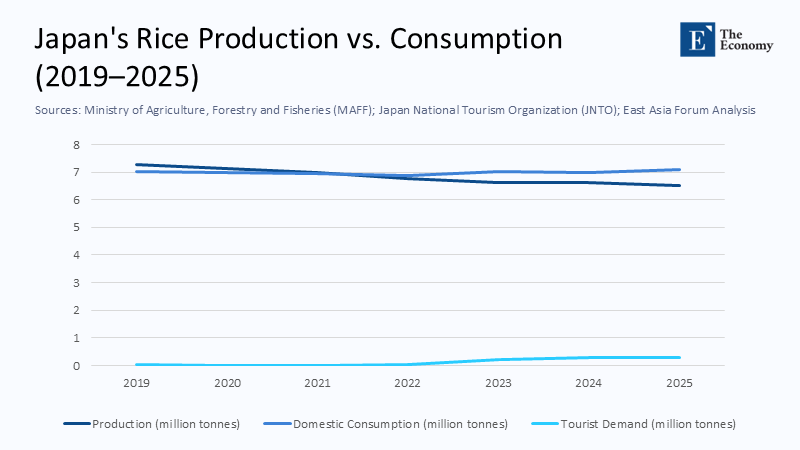

Weather amplified structural shrinkage. Two successive summers ranked among the ten hottest on record, degrading grain quality and increasing breakage during milling. Then Typhoon Shanshan, a Category‑4 equivalent system that landed in Kyushu in late August 2024 with gusts over 250 km/h, flattened paddies across Kagoshima and soaked Hokuriku just days before harvest. Preliminary MAFF tallies put nationwide table rice output for the 2024 crop year at 6.61 million tonnes—nine percent below 2019 and the lowest since the Food Control Act era.

Tourists: The Uncounted Mouths

Yet supply contraction explains only half the story. Demand jumped at precisely the moment planners predicted it would fall. Japan welcomed 36.9 million foreign visitors in 2024, eclipsing the 2019 peak by five million. A Japan National Tourism Organization survey shows the average stay is nine nights, and “eating Japanese food” is the top activity. Convert those data to calories: ninety bowls of rice per visitor—about 0.72 kilograms uncooked—yields an unplanned draw of roughly 266,000 tonnes, equal to four percent of the 2024 harvest and more than one‑quarter of the emergency reserve that MAFF would later release.

The official Food Self‑Sufficiency Report still projects a gentle decline in rice demand on the logic of an aging, carb‑averse population. Tourism is relegated to an appendix. The result is a policy mirage: a statistical surplus on paper masking a physical deficit in convenience‑store storerooms.

Reserves That Wouldn’t Flow

Tokyo’s first remedy was to tap the emergency stockpile. On 14 February, MAFF authorised the release of 210,000 tonnes—about one‑fifth of the one‑million‑tonne reserve and 37 percent of monthly national consumption—in an unprecedented bid aimed not at disaster relief but at market normalisation. The move fizzled. Six weeks after the auction, barely three thousand tonnes had reached supermarket shelves, throttled by milling capacity and the lack of pre‑arranged haulage contracts. Opportunistic wholesalers, facing negative real interest rates, treated unmilled rice as a superior hedge to government bonds and bid 20 percent above futures prices, warehousing inventory in suburban depots. The state possessed volume but not velocity: grain locked in distant silos offered no relief to city shoppers.

The Yen, Inflation, and the Central Bank’s Dilemma

Currency weakness compounded the squeeze. A sub‑¥160 dollar made imported grain cheaper globally, yet domestic prices continued to climb because merchants priced to scarcity, not parity. The Bank of Japan flagged rice as a core contributor to food inflation in its April Outlook, warning that volatility in staple foods complicates the path to interest‑rate normalisation. Every ¥100 rise in retail rice prices adds roughly 0.05 percentage points to headline CPI; that arithmetic forced Governor Ueda to delay a second rate hike, illustrating how a mismanaged agricultural market can bend macro policy.

Historical Echoes and New Differences

The Heisei shortage of 1993 was meteorological: a volcanic winter that halved yields forced Japan to import Thai and Californian rice, triggering a temporary consumer backlash. Today’s crisis is manufactured. Production‑control quotas, aged labour, unpriced tourist demand, and logistic bottlenecks intersected with heat stress. Paradoxically, Japan now exports premium rice—37 ,000 tonnes in 2023 for high‑end sushi chefs abroad—even as it rations at home, because export promotion sits in a different policy silo.

A Korean Counterpoint

South Korea faced similar heat damage but paused acreage cuts in 2020, accelerating the rollout of heat‑tolerant cultivars such as Saenuri. The government still forecasted a two‑percent yield drop in 2024, yet structural oversupply allowed Seoul to ship the symbolic two‑tonne consignment to Japan and to line up a further twenty tonnes. The lesson is stark: policy momentum, not agronomic destiny, determines whether a climate shock ends in imports or exports.

Climate Risk on the Horizon

According to peer-reviewed modelling published in the Journal of Agricultural Meteorology, if Tokyo does not accelerate the breeding and diffusion of heat-resistant rice varieties, rice yields in Kyushu and Tohoku could decline by up to twenty percent by 2050, rising to thirty‑five percent by century’s end under a high‑emissions path. This projection underscores the urgent need for action to mitigate the impact of climate change on rice production.

The Politics of Food Security Funding

While Tokyo has shown awareness of the issue with a supplemental budget in December 2022 earmarking ¥164 billion for food‑security measures, including fertiliser self‑sufficiency and forage crops, it is clear that more comprehensive policy reform is needed. The current allocation reveals an outdated mental map in which food security is equated with domestic production volumes, rather than the complex choreography of demand spikes and supply chains.

Re‑pricing Land and Labour

Restoring balance requires a new incentive structure. A hectare of rice currently nets a farmer about ¥ 300,000—one‑fifth of what high‑value fruits can earn. Unless table rice acreage earns a strategic premium, young farmers will keep shifting to alternative crops or exit altogether. Linking subsidies to productivity benchmarks and carbon‑smart practices, rather than to output suppression, would convert paddies from quota‑managed relics into investable assets.

Baking Tourism into the Demand Model

Tourism is an export consumed at home; every extra bowl sold in Osaka reduces national stocks. MAFF should integrate real‑time visitor data from immigration counters into its supply‑demand projections. Had such an algorithmic trigger existed, the 266,000-tonne tourist vector would have been visible by October 2024, well before rice queues formed, allowing regional governments to lift planting guidance or pre‑position reserve releases.

Reserves Built for Speed, Not Mass

Finally, the stockpile must behave like the petroleum Strategic Reserve: contracts with private logistics firms, milling slots booked in advance, and dynamic release thresholds that match retail inventory surveys. The current model—grain stored for up to five years in rural warehouses—delivers volume but not immediacy. The February auction’s glacial flow showed that velocity is half of security in an age of social‑media panic. Conclusion: Sovereignty Measured One Grain at a Time

Japan’s rice crisis is not a freak caprice of weather or a transient spike in tourist appetite; it is the compound interest of decades of policy aimed at managing surpluses in a world that has quietly pivoted to scarcity. The emergency imports from South Korea mark more than a logistical patch; they signal that the social contract among state, farmer, and consumer is being rewritten under duress. Pride may rebound with the next harvest, but the credibility of ministries, reserves, and the self‑sufficiency mantra will depend on whether Tokyo can recast rice as strategic infrastructure in a hotter, hungrier, and more visited archipelago. Until then, every selfie of a tourist’s sushi platter doubles as a running tally of Japan’s most consequential arithmetic error.

The original article was authored by Seohee Park, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Tohoku University. The English version, titled "Japan faces the bitter harvest of agricultural neglect," was published by East Asia Forum.