Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

A century of evidence from two maritime nations reveals an unexpected constant: forced return migration can accelerate national growth, but only when the state swiftly converts refugees’ losses into asset liquidity. Greece’s Asia-Minor arrivals 1923 and Japan’s Hikiagesha in 1945 represented cataclysmic demographic shocks. Yet the Greek influx evolved into a growth engine, while many Japanese repatriates remained on the margins for decades. Culture and skills do not explain the gulf; both cohorts reached their homelands with broadly comparable educational profiles. The decisive difference lay in the availability of credit, land, and legal certainty during the first 24 months after arrival.

Cataclysmic Departures, Two Oceans Apart

Between August 1922 and the signing of the Lausanne Convention in January 1923, roughly 1.2 million Greek-Orthodox civilians were uprooted from Asia Minor and the Black-Sea littoral and deposited in a homeland of just six million souls. The Lausanne Convention was a significant international agreement that defined the borders of modern Turkey and outlined the rights of the Greek minority in Turkey, which had a direct impact on the forced migration of Greek-Orthodox civilians.

In formal terms, the Japanese shock was more minor—6.6 million soldiers, civil servants, and settlers returned from Korea, Manchuria, Taiwan, and Micronesia between 1945 and 1948, a 9% rise on the archipelago’s war-ravaged population of seventy-two million. In practice, however, Japan’s repatriation absorbed a far larger share of scarce calories, housing stock, and foreign-exchange reserves because the Home Islands were already crippled by bombing, rationing, and hyper-inflation.

The divergent macroeconomic results underscore the urgency and importance of early policy in converting uprooted human capital into bankable collateral. The success of forced-return programs depends less on the number of returnees than on how early policy transforms displaced workers’ skills into productive assets.

Cartography of Collapse and Resettlement

Greece created an International Refugee Settlement Commission (RSC) backed by a League-of-Nations sterling bond that channelled the equivalent of 9% of GDP into land reclamation, seed stock, and low-interest credit. The Commission’s cadastral maps reveal how planners saturated Macedonia and Thrace with 3.6 million stremmata of subdivided farmland and 123 purpose-built villages.

Land titles, not temporary leases, converted peasants into collateral-holding taxpayers. Those certificates soon underpinned small-business loans and school fees. Within a decade, more than one-quarter of national tobacco exports came from refugee farms, demonstrating the long-term benefits of early investment in refugees.

Japan’s institutional reaction was the mirror opposite. The Diet, immobilised by war indemnities and soaring rice prices, dispensed lump-sum allowances that covered barely a tenth of lost colonial assets. Only six of forty-six prefectures experimented with land-grant schemes, and commercial banks, strangled by non-performing loans, extended credit on confiscatory terms. Under these conditions, many Hikiagesha slid into under-employment or the black-market economy. A 1956 prefectural survey found that 40% of repatriate households remained jobless or under-employed more than a decade after their return.

Human-Capital Pivot: Evidence across Generations

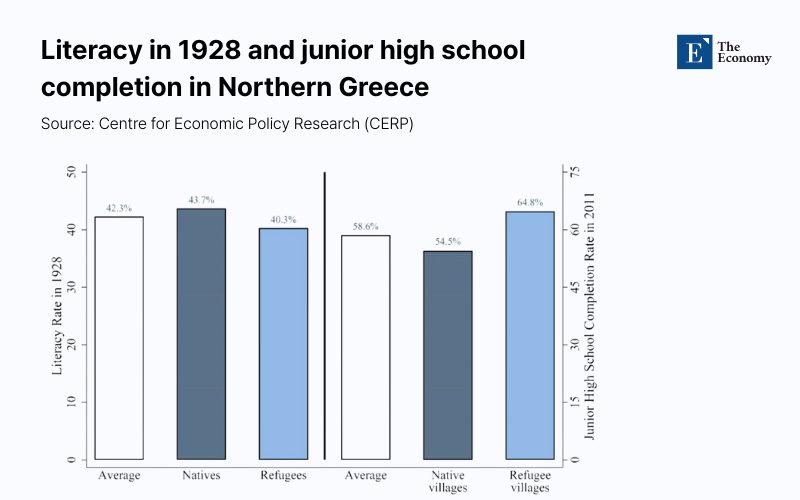

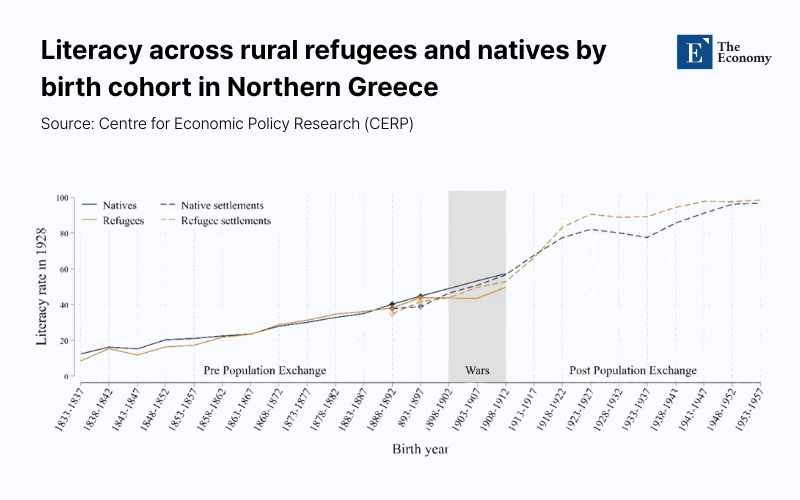

Figure 2 tracks literacy for successive birth cohorts in rural Northern Greece. Until the 1890s, the lines for refugees and natives ran almost tandem. Cohorts born after resettlement show a pronounced divergence: literacy accelerates faster inside refugee settlements despite wartime disruption. The pattern implies a household-level decision to accumulate portable skills once land and credit shield day-to-day subsistence.

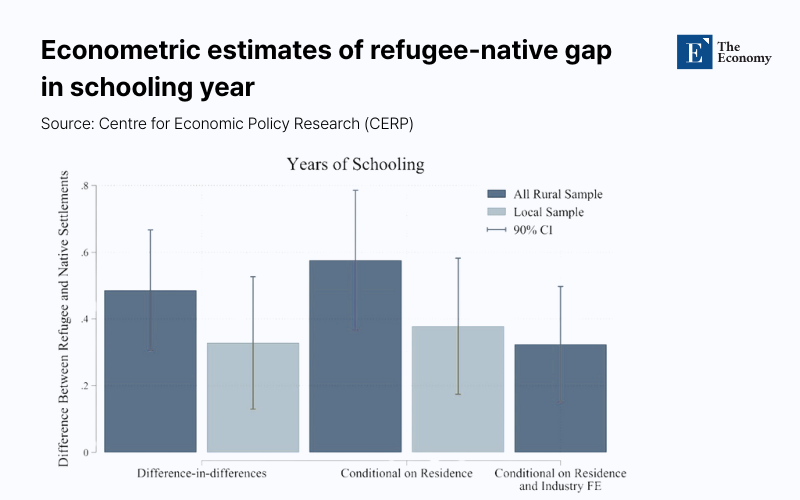

Econometric estimates from Figure 5 quantify that divergence. Even when residence and industry fixed effects are absorbed, thus purging local labour-market composition, the refugee advantage persists at roughly 0.5 schooling years. In other words, the “uprootedness channel” is robust to the usual identification attacks: brains prove a safer store of value when property is fragile.

Japan's archival data tell a starker story. Only 4.2% of Hikiagesha held university degrees in 1965—half the national figure. Their majors were skewed toward clerical public administration and small-scale retail, fields cushioned by lifetime employment guarantees but poor in external portability. The Ministry of Health survey cited earlier logs an eight-to-nine-percentage-point university gap two decades after return. Such inertia cannot be blamed on motivation; it grew from collateralized credit's absence and persistent uncertainty over property restitution.

Asset Liquidity, or Why Greece Jumped the Development Queue

Greek land titling was visible, but cheaper credit was the hidden multiplier. RSC co-operative loans undercut commercial rates by roughly three percentage points; default risk is pooled across entire villages, so individual households could gamble on fertiliser imports, better wheat varietals, or sons’ secondary schooling while still servicing debt. By 1938, the mean farm output in refugee villages outpaced comparable native settlements by 17%.

By contrast, Japan’s Ministry of Finance capped agricultural lending at a nominal ¥3 billion in 1946—less than one percent of wartime public debt and far below pent-up demand. What state credit could not cover, black-market lenders supplied at rates that often exceeded 50% per annum, forcing distress sales. Growth-accounting reconstructions peg the opportunity cost at roughly 0.4 percentage points of total-factor productivity per year between 1946 and 1955.

Skill Portability and the Machinery of Social Mobility

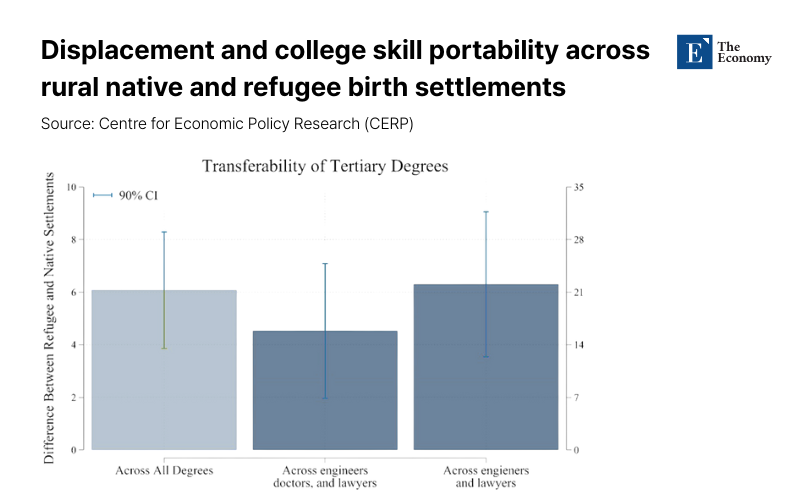

Figure 4 shows that Asia-Minor descendants are more likely to pursue higher education and select majors with international mobility—engineering, medicine—rather than degrees tethered to local legal codes. The wedge is most pronounced in rural settlements, suggesting that the credit-cum-title bundle allowed parents to finance longer academic paths even when immediate farm output could have absorbed their children’s labour.

By contrast, Japanese repatriates clustered into clerical posts and service-sector niches that rewarded experience but rarely traveled well across prefectural borders. Without collateral, long-cycle professional degrees were prohibitively risky, locking families into sectors with limited wage growth.

Network Externalities and Urban Spill-overs

Greece’s urban hubs reaped secondary gains. Pontic bakers introduced steam ovens that halved baking time in Piraeus, and Smyrniote silk merchants rekindled Thessaloniki’s moribund textile guilds. Census micro-data show that by 1940, refugee neighborhoods displayed an occupational Herfindahl index 14% lower than comparable native districts—a proxy for diversification that economists tie to wage resilience, inspiring the potential of such communities.

Japanese port cities did not see equivalent spill-overs. Osaka’s already-saturated home-industry districts absorbed repatriates, nudging the urban wage Gini upward by three points between 1947 and 1953. Entrepreneurship among Hikiagesha lagged that of non-repatriate peers for two decades, muting potential contributions to the incipient electronics boom.

Narrative Economies: How Stories Price Risk

Greek politics quickly framed the Pontioi and mikrasítes as cultural guardians of Byzantine heritage. Refugee candidates captured 15% of parliamentary seats by 1935, giving them leverage over municipal budgets and credit allocation. Japan’s national press, wrestling with defeat, caricatured Hikiagesha as burdensome dependents—in one six-month window of 1946, newspaper references to “kasō-min” (“marginal people”) tripled. Wage regressions controlling for education and prefecture find a repatriate penalty of seven to 12%—a stigma tax still echoed in the 1970s.

Comparative Scale and Policy Load

Earlier, Greece absorbed a demographic shock that was more than twice as large (relative to the host population) as Japan’s, yet it vaulted ahead along human-capital metrics. The episode proves that volume is not destiny; policy is. If collateral and credit appear inside the first planning cycle, displacement becomes a catalyst. A smaller inflow can metastasise into a multi-generational scar when they do not.

Ledger for the Twenty-First-Century Exodus

Ukraine’s urban evacuees, Sudan’s drought migrants, and the low-lying Pacific micro-states now staring at sea-level models all face the same window Greece faced in 1923 and Japan in 1945. Land is scarce today, but digital collateral is not. Portable credit histories, stable-coin escrow wallets, or equity-matched micro-grants can replicate the RSC’s titling effect without a square metre of soil. Conversely, humanitarian stipends minus asset scaffolding risk replaying Japan’s post-war stagnation: wage scarring, social assistance, and grievance will surface just as surely, only later—and with compound interest.

Choosing the Cost Curve

Forced return migration is usually framed as an unavoidable humanitarian loss. History frames it as an investment whose yield is determined by the host state. Greece treated its 20% population surge as a balance-sheet expansion and structured policy accordingly; Japan viewed its smaller 9% inflow as a relief expense and paid the price in foregone growth. Whether today’s displaced become a compounding dividend or a chronic liability depends on whether states transform uprootedness into liquid assets before the first post-exile winter.

By recognising forced return as a capital shock rather than a welfare claim, we shift the narrative from burden to bet. Greece shows the odds are astonishingly in favour of those who stake capital early. The Japanese example reminds us that the cost of waiting is far greater, and the bill, like the refugees, always comes home.

The original article was authored by Stelios Michalopoulos, an Eastman Professor of Political Economy at Brown University, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "How refugees continue to positively shape the Greek economy over a century after they arrived,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.