Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

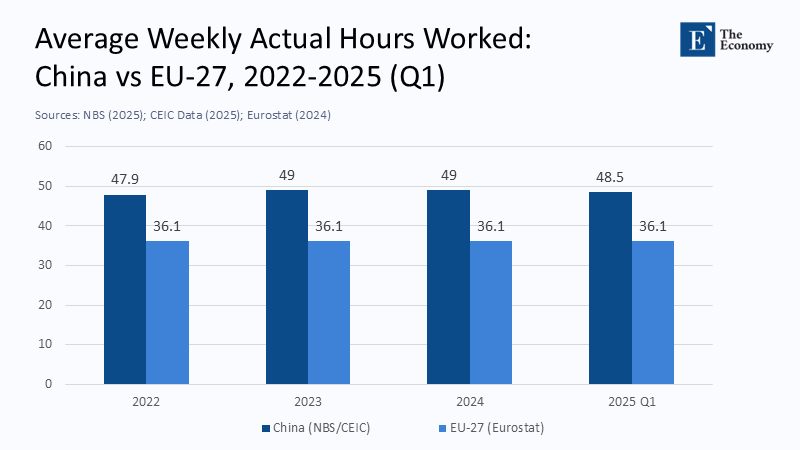

Beijing’s data for the first quarter of 2025 tells a story more revealing than any conference pledge: employees of Chinese enterprises clocked 48.5 hours per week on average —almost twelve and a half hours more than the EU norm of 36.1 hours. That gap has hardly budged since the pandemic, and it widens each time Europe relaxes the schedule of its supply-chain directives. The divergence is not a statistical quirk; it is the product of mutually reinforcing incentives in both jurisdictions that favour the rhetoric of convergence over its costly mechanics.

A Statistical Chasm, Not a Narrowing Strait

Eurostat’s 2023 labour-force release pegs the average working week in the EU-27 at 36.1 hours, which has drifted less than four-tenths of an hour in five years. By contrast, China’s National Bureau of Statistics recorded 48.5 hours in March 2025 after a brief pandemic dip and a rebound that lifted the national series back to pre-COVID peaks. Arithmetic converts that headline gap into a strategic lever: each Chinese production employee supplies roughly one-third more weekly labor time than her European counterpart. In labour-intensive export niches, those surplus hours suppress unit labour costs without the headline risk of visible wage cuts.

The European Ceiling That Became a Marketing Tool

Exporters in Guangdong and Zhejiang now circulate glossy brochures asserting “48-hour compliance” with EU norms. The number is technically accurate only because the EU Working Time Directive sets 48 hours as its legal maximum, not its empirical average. In practice, the Directive’s generous cap is a residual from legislative bargaining in the late 1990s; most European employees work far below it. Chinese suppliers exploit the confusion by demonstrating mathematical conformity to a ceiling Brussels never intended as a performance target. Their paperwork satisfies buyers’ audit checklists while leaving production rhythms unchanged on the shop floor.

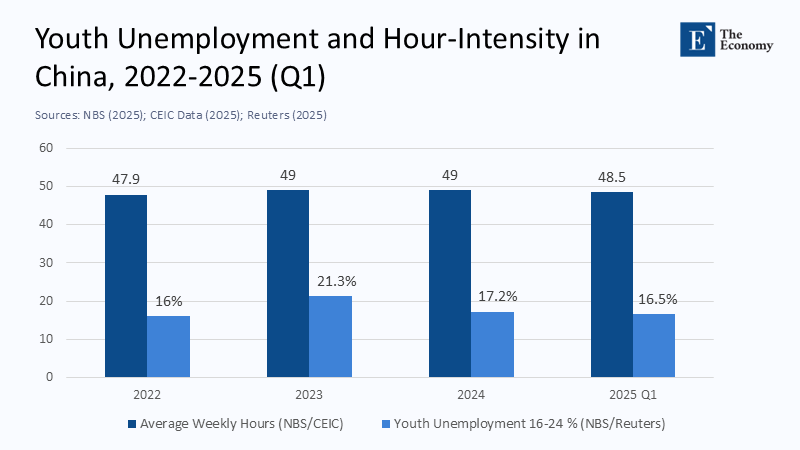

Youth Unemployment: A Slack Engine Driving Overtime

The supply of long hours is rooted in labour slack. After surging to 21.3% in June 2023, the youth-jobless series was withdrawn from public release, sparking criticism from academics and investors alike. Even after Beijing resumed publication with a narrower methodology, the youth unemployment rate stood at 16.5% in March 2025. Under such conditions, a new graduate’s reservation wage falls, and the willingness to accept unpaid overtime rises. Excess supply of educated labor converts directly into hour-intensive schedules, maintaining a feedback loop in which every uptick in youth slack makes Beijing’s twenty-year-old eight-hour day look increasingly aspirational.

Welfare Optics Meet Fiscal Arithmetic

Supporters of a softer turn in Chinese work culture often point to upgraded canteens, meditation rooms, and the sudden vogue for Friday-afternoon “well-work” breaks. These perks photograph well, but they do not challenge the wage-over-hours equilibrium. The Ministry of Finance’s latest budget report shows social-insurance outlays of 9.93 trillion yuan in 2023, barely 2.7% of GDP and well below the OECD median of eight. With public finances stretched by property-sector bail-outs and local-government refinancing, Beijing has little space to co-fund a European-style expansion of paid leave or sick pay. Private firms must foot the bill —and when margins in electronics assembly hover near 4%, management is more likely to install coffee machines than cut rosters.

Automation’s Counter-Intuitive Effect on Hours

China is simultaneously the world’s largest automation buyer. The International Federation of Robotics reports 276,288 industrial robots installed in 2023, amounting to 51% of global demand, and a robot density of 470 units per 10,000 manufacturing workers, third worldwide behind South Korea and Singapore. Yet that automation surge has not dented overtime. Early-stage deployment increases skilled overtime because new lines must be calibrated and supervised, while accelerated depreciation schedules make three-shift utilisation the quickest route to recoup capital costs. In other words, during the transition phase, robots and long rosters have been complements, not substitutes.

Courtroom Victories Without Shop-Floor Muscle

China’s Supreme People’s Court has ruled the “996” schedule illegal, and lower-court verdicts have awarded back pay in emblematic disputes. However, the litigation strategy depends on workers filing and funding claims, a rare event when long hours are the tacit price of entry into urban employment. Nationwide, the labour-safety inspectorate numbers fewer than 4,000 officers, about one per 350,000 employees, a ratio that makes systemic enforcement impossible. The result is a dual regime: high-profile judicial repudiation of extreme overtime and routine hour intensity in everyday operations.

Europe’s Enforcement Vacuum After “Stop-the-Clock”

Across the Eurasian supply chain, incentives hardened on 14 April 2025 when the European Council approved the “Stop-the-Clock” Directive. The law suspends core reporting deadlines under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the new Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) by up to three years. Small and medium-sized EU importers, already struggling with climate-disclosure rules, immediately pushed hour-compliance audits to the bottom of their priority queue. Audit firms say site-inspection bookings for Chinese factories in 2025 are running almost 20% below last year’s pace, confirming that regulatory delay translates directly into on-the-ground complacency.

Data Darkness and Its Invisible Surcharge

At the same time, transparency costs are rising. A Wall Street Journal investigation catalogued more than 400 official data series that have vanished from Chinese portals in the past five years, including subsets of labour statistics. The opacity forces European buyers to price in informational risk through higher trade-credit spreads or to migrate orders to jurisdictions with clearer data trails. Larger importers can absorb the premium; smaller firms often waive in-depth social audits, weakening the external pressure that once nudged Chinese suppliers toward shorter rosters.

When Will Convergence Become Rational?

Analysts frequently claim that rising wages or expanding automation will eventually compress hours, but each dynamic has qualifiers. Based on the National Bureau of Statistics' wage elasticities, a hypothetical return of youth unemployment to its 2017 level of about 12% would lift the average pay for the 20-29 cohort by roughly 11% in real terms. Holding hours constant would slice operating margins in labour-intensive exports by more than half, making productivity-driven hour reductions the logical survival strategy. Conversely, if Brussels reinstates the original 2026 compliance timetable and mandates tamper-proof digital time-keeping, Rhodium Group modelling suggests a 6% hike in landed cost for apparel imports from China, again tipping the calculation toward genuine hour compression. Until one of those catalysts arrives, however, the status quo remains self-reinforcing.

Political Economy of a Long-Hour Equilibrium

Europe gains easy passage for its sustainability rule-book by offering phase-ins and exemptions; China gains competitive traction by staffing long but inexpensive shifts with surplus graduates who would otherwise add to social-stability risk. Both political systems, therefore, collect short-term dividends from a regulatory mirage in which paper standards converge while stopwatch measurements diverge. Workers subsidizing global disinflation with their time are the losers, and policymakers who misread brochure compliance as structural change are the losers.

A Five-Year Outlook Shaped by Two Variables

Barring a surprise tightening in EU audit calendars or a dramatic absorption of China’s graduate surplus, the weekly-hour gap plotted in Figure 1 will likely widen through 2029. Automation will climb, but the coexistence of robots and overtime will persist until debt-laden manufacturers can finance capital deepening without three-shift utilisation. Welfare perks will proliferate because they are cheap signalling devices, not because they redistribute bargaining power. Data opacity will raise financing spreads, prompting some near-shoring, but not enough to overturn China’s scale advantage.

Conclusion: Measuring the Mirage

China is not “bending” its labour model toward Brussels; it is bending the presentation of that model. The numbers are stark: 48.5 hours versus 36.1 even after pandemic shocks, youth-employment crises, courthouse victories against 996, and the most significant automation boom in industrial history. Long hours endure because they solve simultaneous challenges —under-employment, weak domestic demand, and tight private budgets —more cheaply than any alternative. Europe’s delayed enforcement and China’s data darkness conspire to align the incentives. Unless one side changes the arithmetic, the stopwatch will continue to expose a widening, not narrowing, divide at the heart of the Sino-European supply chain.

The original article was authored by Hao Nan, a Research Fellow with the Charhar Institute. The English version, titled "China’s beleaguered work culture bends towards Brussels," was published by East Asia Forum.