Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

That complex reality frames the central claim of this essay: the world can avoid sliding back into the disorderly pre-1994 trade landscape, but only if it engineers a form of multilateralism that is no longer hostage to a single United States veto.

The Marrakesh Miracle and Its Limits

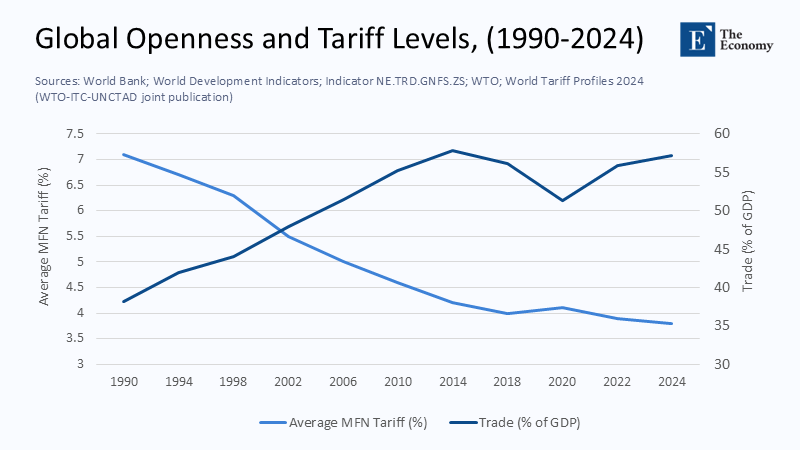

The birth of the World Trade Organization in 1995 codified the most ambitious exchange of tariff concessions in modern economic history. Average applied most-favoured-nation duties stood near seven per cent on the eve of the WTO’s launch; by 2014, they had fallen to roughly 3.8 per cent. Over that same span, the ratio of global trade in goods and services to world GDP climbed from thirty-eight to almost fifty-eight per cent. Each incremental cut in border taxes enlarged adequate market size, lengthened supply chains, and—most visibly in East Asia—pulled well over a billion people above the extreme-poverty threshold.

The bargain, however, carried social costs. Towns in the American Midwest absorbed sharp manufacturing job losses, while southern Europe’s garment districts saw entire production lines migrate to lower-cost Asia. That disruption was not an indictment of globalisation per se but a verdict on domestic policy: the United States halved spending on Trade Adjustment Assistance between 2010 and 2020 even as tariff ceilings kept drifting downward. When the local pain finally found a political voice—most forcefully in the 2016 U.S. election—the stage was set for a deliberate reversal of three decades of incremental liberalisation.

The Protectionist Pivot (2018 – 2025)

Between mid-2018 and the close of Donald Trump’s first term, the median effective U.S. tariff climbed from 2.6 per cent to 4.2 per cent. International Monetary Fund modelling now suggests that the 2018-23 tariff waves will slice six-tenths of a percentage point off world output by 2027 and as much as a whole percentage point over the longer horizon. Trade economist Daniel Gros argues that the risk lies less in the immediate drag on volumes than in the contagious policy signal: if other major economies mirror Washington’s duties, a self-reinforcing spiral will corrode the architecture designed to manage conflict.

The early warning lights are already flashing. UNCTAD’s latest outlook projects global growth decelerating to barely 2.3 percent in 2025, a slowdown linked directly to rising tariff uncertainty. Inside the United States, tariff-induced input costs added at least three-tenths of a percentage point to 2023 core consumer-price inflation, while downstream manufacturers—especially the smallest, least diversified firms—absorbed a cumulative forty-eight billion dollars in extra costs over 2019-20. The jobs tally delivered in return was meagre: manufacturing payrolls grew by roughly three hundred thousand across that period, barely two-tenths of one per cent of the national workforce.

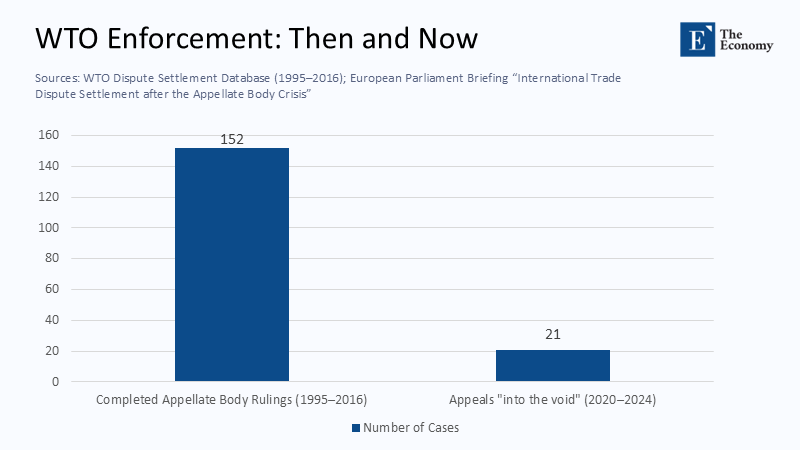

The WTO’s Spine Bends

The WTO’s Appellate Body ensured that panel rulings carried real bite for two decades. It delivered 152 final decisions between 1995 and 2016. Since December 2019, no single appeal has reached judgment because the United States refuses to approve new judges. Without the threat of a binding legal decision, the deterrent power of litigation has evaporated. East Asia Forum captures the gravity neatly, warning that the global economy now stands “on the precipice of a world trade war,” its legal backstop hollowed out just when restraint is most needed.

In the vacuum that follows, tariff ceilings become polite suggestions rather than enforceable limits. The system runs on social trust, and that trust is evaporating fast. It is crucial for each of us, as policymakers, economists, and trade experts, to uphold this trust and work towards a more stable global trade system.

Winners, Losers, and the Data Beneath the Rhetoric

Pro-tariff politicians often argue that protection rescues communities scarred by offshoring. The statistical record paints a very different picture. A 2023 synthesis of forty empirical studies by the Brookings Institution finds that lower import prices still generate consumer-welfare gains of roughly one dollar and fifty cents for every dollar of trade-related wage loss. Those aggregate savings do not flow neatly back to the factory towns that lost their anchor employers—the essence of the distribution problem—but the national balance sheet remains positive.

Equally striking is the mismatch between the scale of tariffs and the modest labour response. During the first tariff wave from mid-2018 to the pandemic’s onset, the United States added only three hundred thousand manufacturing jobs. Meanwhile, tariff-related cost increases rippled through complex global value chains. OECD trade-in-value-added tables show that foreign content already made up more than thirty per cent of the average country’s exports by 2020, up from eighteen per cent in 1995. A duty applied to one link ricochets through every upstream stage, magnifying the original impost far beyond the bilateral trade flow politicians like to cite.

Beyond Nostalgia: Building a Plurilateral Spine for the Twenty-First Century

Inviting Washington to revive its 1994 enthusiasm is politically improbable, at least in the near term. Three structural changes separate 2025 from the Marrakesh moment. First, import demand is multipolar: China, ASEAN, India, and the European Union generate over sixty per cent of incremental global imports. Second, wholly new trade content—cross-border data flows and carbon-pricing at the border—never appeared in the 1994 rulebook. Third, the line between security and commerce has blurred, with export controls on semiconductors and critical minerals outside the WTO disciplines.

The pragmatic answer is to construct a plurilateral backbone inside the WTO, using Article X to let coalitions of the willing bind themselves while keeping the door open to late adherents—including, eventually, the United States. The first plank of that backbone would be a super-majority procedure for appointing Appellate Body judges: vacancies could be filled when two-thirds of members representing three-quarters of world trade vote yes. Simulation work by the Peterson Institute indicates that such a reform would claw back roughly one-third of the welfare the world economy has lost to tariffs since 2018, offering a beacon of hope in these challenging times.

A second plank of the proposed solution would be a digital trade compact. This compact would include chapters on data-localisation bans and source-code non-discrimination, which align with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement. A de facto global standard for digital trade would be created by lodging these schedules at the WTO, potentially reducing trade barriers and promoting digital innovation.

Climate policy forms the third plank of the proposed solution. A plurilateral zero-tariff club for low-emission steel, aluminium, and fertiliser would be established. This club would aim to turn Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism from a potential trade irritant into a liberalising force. The club would incentivize its production and trade by offering zero tariffs on these low-emission products, contributing to global climate goals. The final plank of the proposal addresses supply-chain fragility: members should pledge, with complete transparency, not to impose export bans on critical medical goods or minerals except under tightly defined emergency conditions.

Investment-Side Leverage—Bringing Capital to the Equation

Tariffs directly dampen trade volumes, but investment is the more potent shock channel. OECD inter-country input-output tables suggest that tariff-driven uncertainty shaved two percent off global fixed-asset formation in 2024 alone. Faced with rising border costs, firms relocate capacity to tariff-sheltered markets or shelve expansion plans altogether, undermining long-term productivity growth.

A global Investment Facilitation Agreement, long stalled in Geneva, could be revived by the exact super-majority mechanism proposed for judge appointments. UNCTAD’s econometric models imply that a binding package of transparency rules and dispute-avoidance procedures would lift green-field investment between four and six percent—easily enough to offset the drag now visible in the capital-expenditure data.

Domestic Optics—Compete and Compensate

No amount of legal engineering in Geneva will sustain open markets if voters perceive only risks and no rewards. Two instruments can alter that perception. First, income-contingent lifetime-learning credits financed from a fraction of customs revenue would convert tariff dollars into tangible up-skilling pathways, should Washington persist. Australia’s Higher Education Contribution Scheme provides the template: repayment is triggered only when a beneficiary’s income exceeds a threshold, eliminating the liquidity barrier that traps mid-career workers in declining sectors.

Second, export-linked place-based incentives create geographic bridges into global value chains. Britain’s Freeport programme, which ties tax relief to actual export throughput, lifted local manufacturing investment by four percentage points within three years. Translating that principle to the American Midwest or Britain’s northern counties would link distressed regions to the opportunities global supply chains still offer.

Timelines and Legal Plumbing for CBAM

Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism enters its transitional reporting phase in October 2025 and moves to complete collection in January 2027. By that date, WTO members will either have anchored environmental border pricing in a plurilateral annex or face legal challenges. Explicit reference to the general-exceptions clauses—Articles XX(b) and (g)—combined with a single-window emissions-verification portal for exporters can reconcile CBAM with the core non-discrimination principle of the multilateral system.

Where Next? A Realistic Roadmap

Progress will be measured in incremental but irreversible steps. The first opportunity arrives in June 2025 at the Buenos Aires ministerial mini-conference, where a coalition of Latin American economies can table the super-majority judge-appointment protocol alongside a digital-trade annex. By September 2025, the G20 summit in Delhi offers a stage to announce reciprocal tariff reductions among signatories of the judge-override pact; even a ten-basis-point cut would signal that liberalisation remains alive. January 2026 is the target date for the green-goods zero-tariff club to take effect, eliminating duties on certified low-carbon steel, aluminium, and fertiliser. Two months later, with the Investment Facilitation Agreement in force, mid-sized economies can market “WTO-compliant friend-shoring” zones to multinationals eager for stable, rules-based destinations.

Refusing the False Choice Between Sovereignty and Openness

Protectionists insist that defending national sovereignty requires tariff autonomy. Free-trade purists sometimes respond with a naïve universalism that glosses over adjustment pain. Both camps misframe the debate. The real contest is over whose rules govern the cross-border space that every advanced and emerging economy now depends on. When the United States abdicates, that space does not disappear; it is filled either by unilateral leverage or smarter, more inclusive multilateral architecture.

The data are unambiguous. Tariffs imposed since 2018 have already carved at least six-tenths of a percentage point from projected world output, and global institutions from the IMF to UNCTAD warn of deeper scars if escalation continues. A reinstated dispute mechanism, a modernised rulebook, and a credible programme of domestic compensation could recover roughly half of the lost welfare within three years, even without immediate U.S. participation.

The agenda set out here—super-majority governance, digital and green plurilateral, investment facilitation, and tangible support for workers—neither waits for Washington nor excludes it. Instead, it constructs a pathway back into the system at a time of the United States’ choosing. History suggests that when the economic rewards become undeniable, America eventually returns to the table. Until then, the rest of the world cannot afford nostalgia. The tariff wall is a trap; escaping it requires deliberate, collective engineering.

The original article was authored by Shiro Armstrong and Yose Rizal Damuri. The English version, titled "Avoiding a world trade war," was published by East Asia Forum.