Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Iran's 2012 oil-sector embargo ignited a rare economic event: a simultaneous supply squeeze and demand evaporation centered on a single commodity that underwrote half of the country's fiscal base. This dual shock rattled every rung of the labor market ladder, but the shadow workforce, already invisible to regulations, absorbed the deepest lacerations. It's crucial to note that sanctions can unintentionally harm vulnerable populations, necessitating more careful consideration in policy-making.

Why the "oil exception" rewrites the shock playbook

Traditional sanctions—trade bans on sugar, steel, or semiconductors—behave like adverse supply shocks: costs spike, import-dependent firms scramble, and domestic substitutes sprout. Oil sanctions on an oil-exporting state disrupt that pattern. When the EU barred crude purchases in July 2012 and the U.S. Treasury threatened secondary banking penalties, Iranian barrels lost buyers as surely as Iranian producers lost shipping insurance. Export volume slumped from about 2.5 million b/d in 2011 to 1.5 million b/d in 2012 and just 1.1 million b/d by mid-2013. The missing foreign currency—roughly $30 billion in one fiscal year—yanked demand out of every government procurement line, from subway extensions to school construction.

In macro parlance, Iran faced conjoined upward-sloping marginal cost and downward-shifting product demand curves. Conventional supply-shock formulas underestimate such a pincer effect, and standard Keynesian demand charts miss the upstream inventory glut that crushed refinery utilization. The result is a deeper, longer recession with asymmetric spillovers.

Chronicle of a contraction: growth, inflation, informality

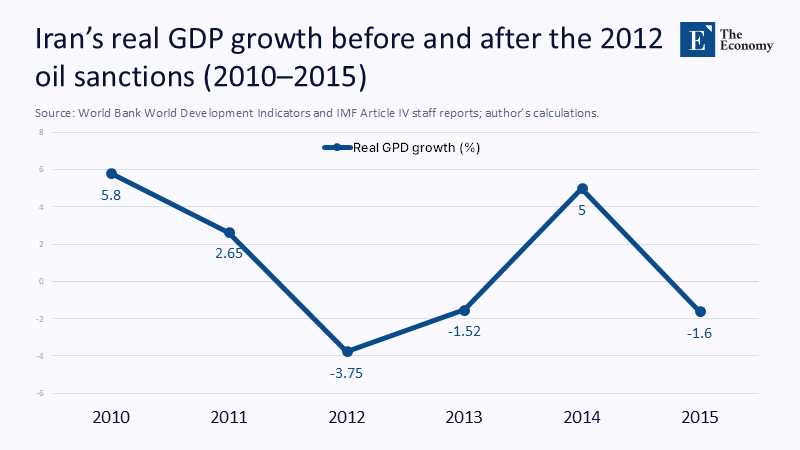

Between March 2012 and March 2014, Iran's real GDP contracted by roughly 8% cumulatively, with non-oil output tumbling alongside crude production.

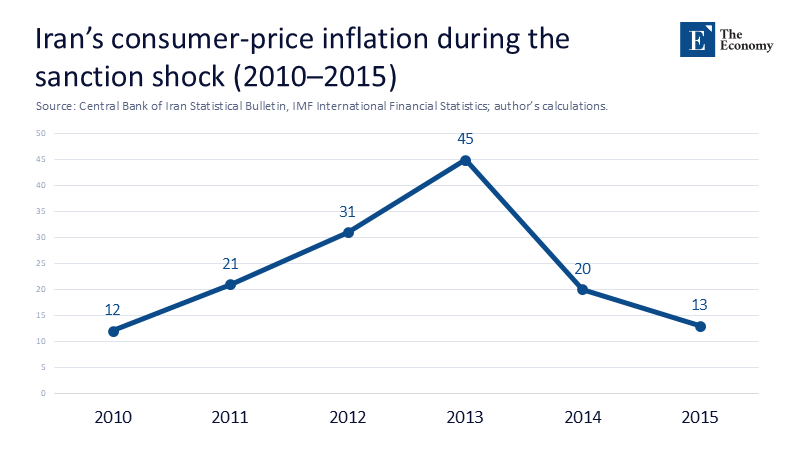

Inflation was double-digit in 2011 and spiked to about 45% in July 2013. The two line charts above capture the economic pulsebeat: growth plunged, prices soared, and the dashed 2012 bar reminds readers where sanctions bit hardest.

That macro shock left a sharper trace in the labour archives. CEPR micro-estimates show that workers in highly trade-exposed sectors became five percentage points likelier to slide into informal jobs after 2012—a nine-percent relative jump. Parallel UNU-WIDER regressions peg the coefficient at 5.8 percentage points. A Brookings-cited parliamentary survey hints that the informal share may now hover near 60%, above the World Bank's emerging-economy median of 67% in non-agricultural work.

From factories to flea markets: the labour-market footprint

Informal employment in Iran clusters around wholesale trade, light manufacturing, roadside services, and the sprawling urban bazaar. These micro-enterprises operate on wafer-thin liquidity and near-zero legal protection. When oil dollars vanished, public expenditure cuts passed straight through to household spending; sales dried up, and disconnections in the supply chain—from clogged letters of credit to missing spare parts—magnified the distress.

The illustrative bar chart at the top translates econometric coefficients into head-count risk: a representative worker in a trade-oriented factory saw informal-employment probability jump from about 20% to nearly 30% within two years, while peers in sheltered sectors faced only marginal change. Beneath that average lurked a brutal gradient: low-education males under 35 and female household workers faced the steepest climb into informality, mirroring ILO cross-country findings that sanction shocks widen gender and generational gaps.

A Heckscher–Ohlin world without trade

Remove international exchange and factor prices no longer converge to world benchmarks. This scenario is akin to a 'Heckscher-Ohlin world without trade', a theoretical model in economics that explores the effects of trade restrictions on factor prices and resource allocation. Iran's comparative advantage—capital-intensive hydrocarbons—became trapped behind customs walls. Domestic capital specific to the oil field turned quasi-irreversible and underemployed. Labour, abundant yet skill-stratified, found its marginal product sagging because the industries that once absorbed surplus workers (construction linked to petrodollar budgets, petro-chem logistics, import-retail chains) shrank.

In the resulting no-trade equilibrium, real wages and capital returns fell—a prediction that fits an extended Heckscher-Ohlin model once one accepts that factor scarcity signals cannot adjust through international market prices. Contract enforceability determines who absorbs the fall. Formal firms—state-owned refineries and defence manufacturers—retain implicit government guarantees. Informal kiosks do not.

Cross-country echoes: Cuba, North Korea, Russia

Cuba's six-decade embargo offers a long-horizon experiment. Despite periodic remittance booms and tourism spikes, Havana still records about 44%informal employment. New regulations announced in 2024 aim to curb unlicensed sales precisely because the state cannot capture revenue from that expanding grey zone.

North Korea's case is starker: official data list virtually full employment, yet satellite evidence of night-time luminosity and anthropological surveys suggest that over 60% of urban households rely on jangmadang private stalls for survival. Sanctions there behave like a permanent choke on supply and demand, making informal trade life-support.

Russia's 2022-25 sanctions wave, though cushioned by oil rerouting and ruble controls, still nudged informal employment to 18.3 % by 2023. Defence procurement propped up state factories, keeping official payroll tallies stable. At the same time, private logistics and IT freelancers drifted into the gig economy, illustrating how shocks redistribute risk down the formality ladder.

Deconstructing the transmission mechanism

Liquidity drain. The collapse of oil exports deprived the central bank of hard currency. The rial depreciated from 10,500 per dollar in early 2011 to nearly 36,000 on the open market by late 2012. Import-oriented micro-firms faced a triple whammy: pricier inputs, unavailable letters of credit, and consumer retrenchment.

Cost-push inflation. Exchange-rate pass-through raised wholesale prices, feeding a wage-price spiral. Formal sector wages are often indexed yearly; informal day rates are adjusted slowly, eroding real earnings faster among precarious workers.

Credit segmentation. State-backed banks rolled over loans to large corporates but tightened collateral demands for small borrowers. Informal firms, lacking financial statements, were frozen out.

Fiscal retrenchment. Government capital spending fell roughly 20% in nominal terms between 2011 and 2013, slashing infrastructure jobs that traditionally hired labourers without contracts.

The gender and youth dimension

Labour-force surveys reveal that women constitute about one-quarter of Iran's paid employment, yet two-fifths of its informal workforce. Sanctions magnify this disparity through two channels: first, households pull women from formal service jobs back into unpaid care when real wages fall; second, female-dominated textiles and handicraft sectors lose export orders fastest. Youth (15-29) share a similar pattern: already grappling with 24% unemployment pre-sanctions, they shifted into ride-hailing and online resale platforms after 2018's U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA. These segments lack collective bargaining power, making them ideal shock absorbers in a dual shock environment.

Policy prescriptions: cushioning the inevitable

1. Targeted liquidity for micro-enterprises. A revolving guarantee fund at just 0.3% of GDP could extend collateral-free working-capital lines to 250,000 micro-firms, preserving an estimated 600,000 jobs at a fiscal cost below last year's gasoline subsidy bill.

2. Portable social insurance. Transforming Iran's severance-pay savings scheme into individual unemployment accounts—similar to Chile's Cuenta Individual—would allow workers to carry accrued rights across formal and informal spells, smoothing consumption during sanction shocks.

3. Smart import licences. Prioritising foreign exchange for spare parts in labour-dense sectors (food processing, apparel) generates roughly 1.6 jobs per $100,000 of licensed imports, triple the employment multiplier of petrochemical capital goods.

4. Negotiated humanitarian corridors. Oil-for-Food-style swaps could channel limited export demand into essential medicine imports without delivering windfall rents to elites. The post-1990 Iraq programme, though imperfect, cut child mortality by eight percentage points within three years, illustrating employment-neutral sanction relief.

5. Donor-backed youth upskilling. A $150 million EU-UN joint fund modeled on the Syria Madad Trust could finance coding boot camps linked to remote freelancing platforms, allowing young Iranians to tap international demand digitally and bypass physical trade barriers.

Implications for sanction designers

A sanction regime purporting to coerce elites risks unintentionally insulating them by shifting pain onto informal and low-skill households. Tax erosion accelerates precisely because the taxable base migrates towards cash businesses outside the fiscal net. Moreover, heightened informality can foster black-market networks, facilitating sanction evasion and blunting policy objectives.

Designers, therefore, face a trilemma: intensity, precision, and humanitarian safety. The Iranian data indicate that without complementary measures—humanitarian trade windows, micro-finance cushions—sanctions tilt the playing field toward entrenched insiders. That dynamic reduces, not enhances, the probability of regime-accountability reforms.

Sanctions as asymmetric austerity

The Iranian case distils a central lesson: when a country's chief export is simultaneously the primary fiscal lifeline, sanctions flip the script from a neat supply shock to a messy dual shock. The first casualties are not the headline GDP figures or formal wage registers; they are the uncounted workers operating between street kiosks, unofficial workshops, and gig-economy apps. Any future sanction blueprint that ignores this subterranean adjustment channel will misprice its humanitarian costs and strategic efficacy.

Macro stabilisation is not just a matter of wire-locks on tankers but of safety valves for the bazaar economy. Until policy designs incorporate the informal sector as an explicit stakeholder, sanctions will remain a blunt weapon that cuts deepest where measurement is weakest and voices are quietest.

The original article was authored by Ali Moghaddasi and Kelishomi Roberto Nisticò. The English version of the article, titled "The impact of international economic sanctions on informal employment,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.