Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The system that turned the Nordics into a byword for egalitarian prosperity is approaching a breaking point. This system, the Nordic welfare state, is not just a model but a cornerstone of our society. Wage compression—once a surgical tool to tame inflation and disarm class conflict—now dulls the price signals required to shift labour toward the green transition, the digital economy, and an ageing population that must be served rather than merely funded. Equality has become so inexpensive to preserve that it is, paradoxically, impeding the growth required to pay for the next chapter of the welfare state. Our work is not just about analyzing challenges, but about preserving and strengthening a fundamental system to our society.

Compression Becomes Congestion

However, the potential benefits of labor market reforms are significant and can lead to a more dynamic and competitive economy. Every multi-year wage round still opens with a cautious settlement in export manufacturing, a “mark” that all other unions and employers dutifully shadow. The architecture keeps Gini coefficients for gross earnings roughly one-third below the OECD median—textbook proof that solidarity and competitiveness coexist. Yet those same settlements also crush the relative wage differentials that ordinarily coax workers into new firms, occupations, or regions. Eurostat’s experimental statistics show that quarterly job-to-job transition probabilities are stuck at nearly 5% in Sweden and Denmark, versus more than 7% in the United States. Reallocations that used to happen silently through market wages now require noisy, often contentious policy interventions.

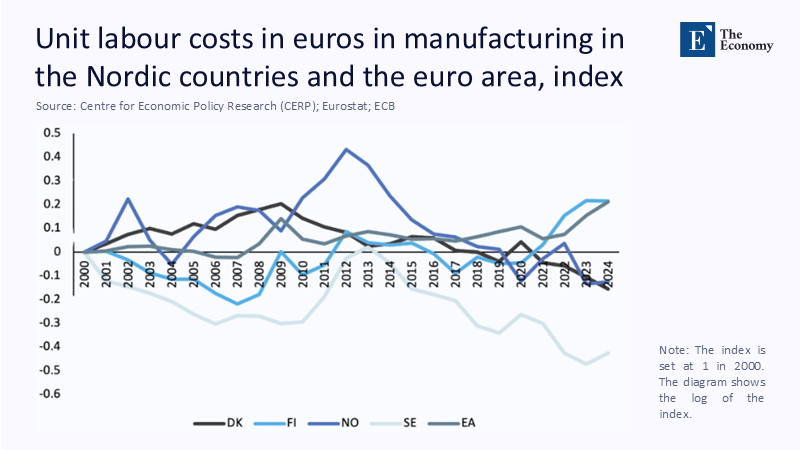

The costs of that rigidity appear first in the traded sector itself. Figure 1 tracks unit labour costs in Nordic manufacturing since 2000 against the euro-area average. Denmark (red) and Finland (blue) have diverged in opposite directions: the former holding its line, the latter letting costs surge in the 2010s before a sharp correction. Norway’s krona-denominated wages (green) oscillate with oil prices, while Sweden’s costs (yellow) have drifted steadily downwards. The takeaway is sobering: the one mechanism designed to keep relative labour costs predictable is already fraying under divergent productivity paths—and it is doing so before the demographic crunch truly bites.

Union Membership Versus Coverage: Democracy on the Cheap

Behind the macro numbers lies a subtle political drift. Union membership has fallen from roughly 80% two decades ago to about 64% in Sweden and the low-60s in Denmark and Finland, even as collective-bargaining coverage still hovers near 85%. In practice, an ever-smaller share of workers vote on wages that effectively bind almost everyone else. The median union voter is older, deeply embedded in the existing pay hierarchy, and therefore instinctively wary of wage dispersion that might reward newcomers or migrants. A governance model celebrated for its inclusiveness is incubating its representational deficit.

The Tax-Wedge Dilemma

Policy-makers often reply that progressive labour taxation can mop up any inequality central bargaining misses. Yet the same wedge that compresses disposable incomes also compresses the rewards to mobility. A single, childless worker on the average wage in Sweden faces a combined wedge of roughly 43%, nine points above the OECD mean. Administrative micro-data reveal that every extra percentage point in the wedge cuts inter-county migration by about 2.4% after controlling for housing prices, age, and schooling. Equality is preserved at the cost of regional rebalancing, which an ageing society desperately needs.

Productivity Shadows: Floors That Hide the Peaks

Compression’s second blind spot emerges at the firm level. In Norwegian manufacturing, the most productive decile of plants generates almost three times more value added per worker than the bottom decile, yet negotiated wage floors rise by barely 25% across that chasm. Wage drift—bonuses and local top-ups—partially smooths the mismatch, but drift is heavily skewed toward incumbents. For younger or newly hired staff, the official floor is effectively the ceiling, muting any financial incentive to jump ship in search of more dynamic employers—mobility stalls, and with it, the diffusion of innovation.

Ageing Shock Meets Care Gap

The Nordic welfare state is bracing for an upheaval on a scale not seen since the 1990s banking crisis. Eurostat projects Sweden’s old-age dependency ratio will climb from 34% today to 48% by 2040, with Denmark, Finland, and Norway not far behind. This demographic shift is not a distant concern but a pressing issue that demands immediate attention. Maintaining current staffing ratios in elder-care alone will require roughly 900,000 additional workers across the four economies—nearly the entire Danish labour force. Norway’s health-and-care vacancies already jumped 46% between 2018 and 2023. Yet pattern bargaining tethers public-sector wage growth to the export norm, suppressing the relative price signal that might lure nurses, geriatric technicians, and care aides into the sector. Unless bargaining rules bend, the Nordics face an unpalatable three-way choice: import labour on a scale that tests social cohesion, ration care quality, or both.

Cross-Border and Internal Mobility: The Empirical Record

Employment-to-population ratios remain the envy of continental Europe—above 77% in Norway, Denmark, and Sweden—but high stocks conceal sluggish flows. Only 19% of Nordic employees switched employers in 2023, down from 43% during the immediate post-pandemic rebound. Cross-border commuting across the Øresund corridor involves fewer than 15,000 daily travellers, despite a potential catchment in the hundreds of thousands. The deeper problem is psychological: OECD surveys report that Nordic workers perceive the payoff to changing jobs as the lowest among twenty peer economies. Nominal compression has become behavioural glue.

Active Labour-Market Policies: Insurance or Inertia?

Generous active labour-market policies (ALMPs) are often touted as the antidote to wage rigidity. Yet, OECD evaluations of pandemic-era job-retention schemes expose a trade-off: subsidies that preserve existing matches can also freeze reallocation precisely when technological shocks accelerate. Public employment services across the region are scrambling to digitise vacancy matching and personalise coaching. Early pilots in Finland shorten unemployment spells by 15% when AI nudges are bundled with training vouchers—proof that institutional plumbing matters. Still, even the most innovative matching algorithm struggles when relative wages refuse to nudge workers toward chronically understaffed occupations.

Scale-Up Leakage and the “Grow-and-Go” Syndrome

High-growth “scale-up” firms created nearly 200,000 net jobs in the Nordics between 2017 and 2020, yet an OECD follow-up finds many relocate once they exhaust the domestic talent pool. Founders cite two culprits: narrow wage bands that hinder recruiting experienced engineers away from incumbents and immigration regimes optimised for blue-collar manufacturing rather than digital niches. Wage coordination, in effect, exports the Nordics’ most dynamic employers.

The Green Transition: New Demand Shock, Same Old Constraints

The European Green Deal is forecast to add 2.5 million jobs EU-wide by 2030, tens of thousands of which should land in wind—and hydrogen-rich Nordic regions. Yet recruitment already lags: One in three Nordic citizens fears displacement by the green shift, while employers bemoan shortages of electricians, welders, and data analytics specialists. Wage compression again plays spoiler; when sectoral pay cannot rise above the manufacturing norm, the private incentive to retrain collapses, and the fiscal state ends up footing the bill.

Portfolio Unionism: A Doctrine for a Grey-Green Transition

Unions can remain guardians of equality only if they pivot from wage sentries to portfolio managers of life-cycle earnings. The Calmfors proposal for an independent Norm Council—revived in the Nordic Economic Policy Review 2025—would allow temporary departures from the export norm when vacancy-to-applicant ratios breach pre-set triggers. But councils alone cannot overcome insider vetoes. A sturdier fix is to embed contingent corridors within collective agreements themselves: keep wage floors, but let ceilings widen automatically in sectors where shortages persist for six consecutive quarters, snapping shut once the market cools.

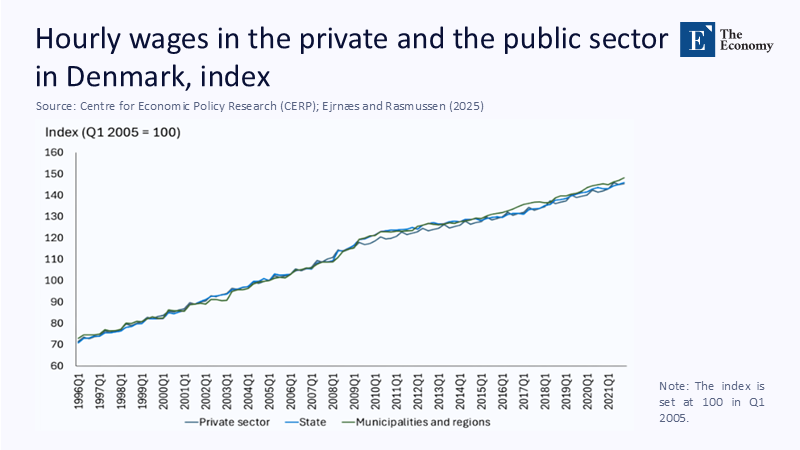

Danish evidence shows that relative public-sector wages already inch up during protracted shortages, though never enough to outpace manufacturing. Figure 2 visualises incrementalism: Danish hourly wages have marched near-lockstep regardless of employer type since the mid-2000s. If vacancies are to be filled without wholesale immigration, the corridors must widen faster than this gentle slope suggests.

A Targeted Fiscal Blueprint

Blanket payroll-tax cuts waste scarce fiscal space. Instead, finance ministries should trial three-year, three-percentage-point rebates on employer social-security contributions in long-term care, triggered when vacancy ratios breach agreed thresholds. Swedish register micro-simulations indicate such a rebate would raise care-sector wages by about 2% and pull in roughly 9,000 workers at a cost below 0.1% of GDP. Couple that with an expanded in-work tax credit worth 2% of taxable income for employees who switch ISCO codes within two years, and job-to-job mobility could jump 15%, closing half the gap with the OECD average.

Compression With Circulation—or Compression in Retreat

Collective bargaining once served as a macro-prudential stabiliser, shielding small open economies from the wage-price spirals that plagued their larger neighbours. A stabiliser, however, becomes a straightjacket when the shocks mutate—from inflation in the 1970s to ageing, decarbonisation, and digitalisation today. Figure 1 shows how unit labour costs diverge across economies supposedly coordinated by a standard benchmark; Figure 2 reveals how even protracted skill shortages barely disturb the wage trajectory. Conditional flexibility—anchored in negotiated corridors, vacancy-triggered fiscal rebates, and mobility insurance—offers the most doctrinally consistent way out. Equality without mobility once made the Nordics exceptional; equality through mobility will decide whether that exceptionalism survives the century.

The original article was authored by Lars Calmfors, a Professor Emeritus of International Economics at the Institute for International Economic Studies, Stockholm University. The English version of the article, titled "The Nordic model of wage coordination at a crossroads," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.