Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The most subversive development in African politics over the past decade is not an upstart party, a constitutional rewrite, or a charismatic reformer, but the collapsing marginal cost of a megabyte. As prepaid data prices drift downward, the economics of attention reshuffle: women who once rationed every text now spend enough bandwidth to campaign, deliberate, and ultimately contest for office. The story of widening female representation in sub-Saharan parliaments is best read as a price narrative, not merely a rights narrative. Scarcity of discretionary income, rather than scarcity of ambition, long muted half the electorate; once the cost hurdle fell, the median voter stopped being implicitly male.

Cost, Not Chromosomes—Re-centring a Stale Debate

International agencies regularly frame the digital gender gap as a clash of norms, stereotypes, or patriarchal gatekeeping. Those barriers loom large, yet the arithmetic of affordability is at least as decisive. The International Telecommunication Union estimates that only about 30 % of African women were online in 2023 compared with roughly 40 % of men. The ten-point spread shadows the ten-to-fifteen-point gap in disposable income that household surveys report across the region. Overlay that with the Alliance for Affordable Internet's finding that a single gigabyte still devours 5.7 % of the average monthly income—almost triple the "1-for-2" affordability benchmark—and the causal chain clarifies: when the utility cost of a political tweet rivals the price of a school meal, families triage. Because women shoulder more unpaid care work and thus have less cash flexibility, they reduce their online presence first. Remove or subsidise that cost, and the gender gap contracts without a single consciousness-raising workshop.

A Continental Natural Experiment—Free Basics as an Unplanned Randomised Trial

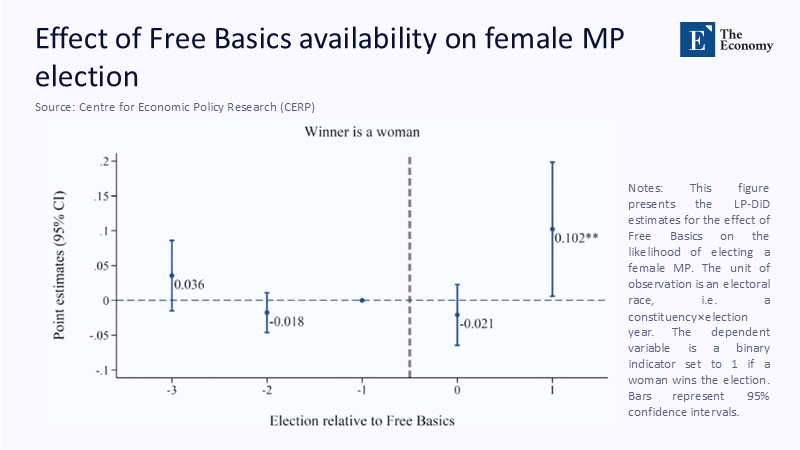

Serendipity supplied the leading test of the price thesis. Between 2014 and 2022, Meta's zero-rating programme, Free Basics, rolled out in staggered waves across seventeen African countries. Economists Sophie Hatte, Jordan Loper, and Thomas Taylor exploited that sequence as a quasi-natural experiment, comparing constituencies before and after free access arrived. Their difference-in-differences estimates reveal that districts enjoying two full years of free Facebook became 10.2 percentage points more likely to elect a female member of parliament in the second post-treatment ballot—an effect significant enough to erase roughly one-third of the baseline gender deficit.

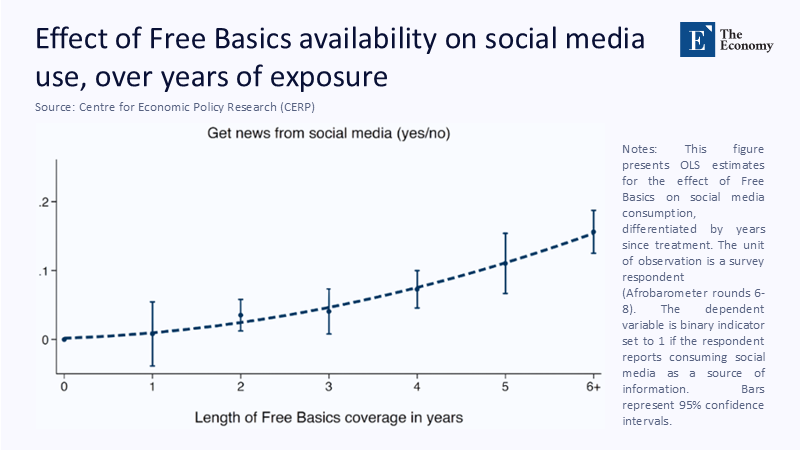

Figure 1 illuminates the behavioural conduit behind the electoral shock. In the first year of free access, news consumption from social media scarcely budged—digital habits take time to form—but by year six, nearly one in four additional respondents cited Facebook or WhatsApp as a primary news source. That silent accumulation of information access matters because Afrobarometer's panel shows that women who receive news online are three to four percentage points more likely to discuss politics with peers and to attend a campaign rally than their offline counterparts.

Figure 2 translates that behavioural churn into ballots. The first election after exposure (year 0) shows no statistically meaningful change—mobilisation needs gestation—but the subsequent race delivers a double-digit leap in the probability that a woman wins. Parties internalise the new economics: once digital word-of-mouth can be fanned at negligible cost, female novices evolve from token list fillers to plausible vote magnets.

Elasticities of Voice—Putting Numbers on Empowerment

To convert those visuals into policy-friendly metrics, consider a back-of-the-envelope elasticity. Afrobarometer's 39-country media survey indicates that a ten-point rise in "social media at least weekly" use among women predicts a three-point uptick in self-reported political discussion and a two-point gain in campaign attendance. Combine that behavioural gradient with Free Basics' observed 15.6-point jump in regular social-media news sourcing after six years, and you foresee a 4.7-point increase in active civic engagement—remarkably close to the five-point fall in male incumbents' margins documented by the CEPR paper. In other words, the ratio of representation appears roughly proportional to the ratio of affordable bytes.

Commercial industry data reinforce the point. The GSMA's Mobile Gender Gap Report 2024 records that when African operators trimmed effective data tariffs by even 15 % in 2023, the regional gap in mobile internet adoption narrowed four percentage points—the sharpest improvement since 2019. Notably, the absolute number of newly connected women worldwide, 120 million, exceeded that of men for the first time, a milestone that happened without any global treaty or splashy empowerment campaign.

From Connectivity Shock to Policy Blueprint—Subsidise the Pipe, Not the Poster

Recasting digital inequality as an affordability puzzle reorders the policy menu. First, it favours capital over counselling: regulators can auction spectrum with strict coverage and tariff conditions, accelerate cross-border fibre consortia to slash wholesale rates, and waive value-added taxes on low-end smartphones. Second, the reframing sharpens the cost-benefit calculus. A Guardian-reported survey of 3,000 female entrepreneurs across 96 developing nations found that 45 % ration online hours because data is dear, a bottleneck the Cherie Blair Foundation estimates could shave $1.3 trillion off developing-world GDP by 2030 if left unsolved. If regulators knock the consumer price of a gigabyte down to two % of monthly income—the "1-for-2" benchmark—they unlock not just votes but venture receipts. Third, the lens clarifies accountability: when data-to-income ratios stagnate, citizens know which authority or operator failed, rather than blaming amorphous patriarchy.

Beyond Price: Network Geometry, Safety, and Electricity Still Matter

Affordability is a necessary but insufficient condition for empowerment. The topology of online networks—who follows whom—determines whether exposure converts into influence. Afrobarometer finds that women who use social media are 8.7 % more likely to support equal political opportunities and 20.5 % less likely to endorse male job preference. Yet, those attitudes evaporate in echo-chamber provinces where over three-quarters of Facebook ties are local. Diversity of connection, not mere gigabyte volume, predicts norm diffusion. The OECD echoes that caution, warning that algorithms can entrench offline segregation unless regulators insist on transparent recommender audits and empower users to curate feeds.

Safety constitutes the second constraint. Zero-rating can inadvertently flood timelines with disinformation or amplify harassment, and studies show that online abuse drives women offline faster than men. The same Guardian survey reports that 57 % of female entrepreneurs experienced digital harassment, double the global male average. Cheap data with toxic content still silences. Thus, affordability initiatives should be paired with legal recourse mechanisms and platform-level tooling to mute abuse.

Finally, the best per-megabyte tariff is useless if users cannot keep a handset lit. In rural Zambia, where grid reliability averages six hours per day, fieldwork from the World Bank finds that the all-in cost of connectivity (tariff + charging + travel to a charging point) exceeds 10 % of monthly income even when raw data rates fall below the 2 % benchmark. Any universal-service plan must therefore braid spectrum subsidies with mini-grid roll-outs or solar-satchel financing to avoid false affordability.

Fiscal Arithmetic—Why a Gigabyte Subsidy Beats a Quota

Sceptics may ask why governments should bankroll bandwidth instead of simply legislating quotas. The fiscal arithmetic is revealing. Rwanda's 2003 constitutional quota fixed female parliamentary representation at 30 %, yet the treasury still underwrites yearly voter-education campaigns, MP training, and enforcement audits. By contrast, Kenya's Lipa Mdogo Mdogo pay-as-you-go smartphone initiative cost $56 million in foregone import duties. Within its first year, it connected 1.5 million low-income users—750,000 women. The incremental cost of each newly connected woman ($75) compares favourably with the estimated marginal cost of recruiting quota-compliant candidates ($1,100) when training, compliance, and monitoring are included. No wonder fiscally pressured ministries find bandwidth subsidies politically palatable: they purchase competitiveness and representation in a single line item.

The Macroeconomic Dividend of Elected Women—Closing the Causal Loop

Representation is not merely cosmetic. An expanding empirical literature shows that female legislators alter fiscal priorities toward health, childcare, and local infrastructure—all of which enhance long-run productivity. A 2024 cross-country panel by the African Development Bank links every five-point uptick in female parliamentary share to a 0.3-percentage-point rise in annual GDP growth, mediated through higher female labour-force participation and lower infant mortality. That macro dividend magnifies the return on bandwidth subsidies: the initial fiscal outlay seeds political change, catalyses growth, and raises taxable income. In net-present-value terms, a gigabyte subsidy can pay for itself within a single electoral cycle.

Building a Low-Tariff Civic Highway—A Sequenced Agenda

A coherent, cost-first playbook might unfold in three phases. Phase I: Wholesale Discipline. Regulators compel network-sharing on rural backhaul, cap termination fees, and auction mid-band spectrum with "use-it-or-lose-it" clauses tied to parity in male-female data usage. Phase II: Retail Pass-Through. Universal-service funds reimburse operators quarterly but only after independent audits confirm that introductory tariffs undercut the 2 % income benchmark. Phase III: Device and Power Integration. Micro-finance institutions bundle pay-as-you-go smartphones with solar chargers, while ministries exempt such bundles from import VAT. The entire sequence is gender-neutral in statute, yet gender-transformative in outcome because women constitute the modal marginal subscriber once prices fall.

Cheap Bytes, Priceless Voices

The experiments documented in Figures 1 and 2 offer an unambiguous lesson: women's political silence was never innate—it was priced. When a gigabyte costs less than a bus fare, Facebook morphs into a soapbox, WhatsApp groups become campaign schools, and female candidacies move from novelty to normal. The CEPR natural experiment verifies the causal link; ITU, GSMA, and Afrobarometer datasets chart its replication; OECD research warns of second-order risks. The policy implication is clear: if a democracy wants more women in parliament, it should start by making their data bundles cheaper than their silence. Anything less concedes the public square to those who can already afford it.

The original article was authored by Sophie Hatte, an Associate Professor of Economics at École Normale Supérieure De Lyon, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Digital access and gender representation: The case of a major connectivity shock in sub-Saharan Africa," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.