Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

If regulatory certainty were a currency, Brussels would be a mint; yet in the marketplace that matters—capital, compute, and talent—the euro is depreciating against the silicon-backed dollar. This divergence is not a mere coincidence; it is the compound interest on five years of hyper-prescriptive AI law-making, and it demands our immediate attention and action.

The First-Wave Balance-Sheet: Regulation, Risk and the Missing Billions

In 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) announced a new European doctrine: citizens must never be the collateral damage of data-hungry business models. The AI Act, the Digital Services Act, and the Digital Markets Act extended that credo from privacy to algorithms and platforms. These texts elevated consumer rights to constitutional status at a measurable industrial price. Atomico's latest State of European Tech puts complex numbers on the bill: venture investment across all tech sectors plateaued at $ 45 billion in 2024, yet only $ 11 billion flowed into AI start-ups—a figure the Bay Area matches in five spring weeks. Meanwhile, the United States poured $ 47 billion into AI alone, widening a funding gap once deemed cyclical but now structural.

Compliance costs amplify the capital drought. A CEPS impact study shows that building the quality-management system required for one "high-risk" AI product runs a small company between €193,000 and €330,000 up front, with €71,400 a year in maintenance. That line item often exceeds payroll for a ten-person spinout in Leuven or Turin, effectively a negative subsidy on innovation. Seen through a balance-sheet lens, the EU has imposed a latent tax of roughly eight to twelve percent of operating budgets on early-stage AI firms, money that would otherwise buy GPUs, data annotation, or patent counsel.

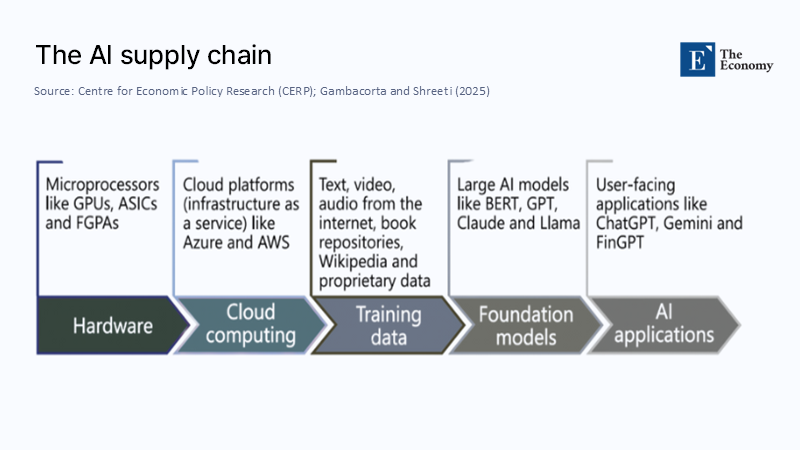

An Inside Look at the Supply Chain Europe Is Regulating

The AI value chain unfolds in five capital-intensive steps: hardware, cloud, data, foundation models, and end-user applications. Europe excels in only one of them—applied robotics and some vertical software—and regulates all five. That asymmetry is visible in the cluster geography of high-performance computing.

Of the world's supercomputers capable of training frontier-scale models, only LUMI in Finland and Alps in Switzerland break into the global top ten, and even they trail the U.S. exascale trio of Frontier, Aurora, and El Capitan by an order of magnitude.

Big Tech's infrastructure narrative is still more lopsided. SemiAnalysis documents at least a dozen GPU clusters exceeding 100,000 Nvidia H100s under construction—each a $ 4 billion bet that compute, not code, is the ultimate moat. All but one are in North America or East Asia. European researchers must rent cycles from Azure or AWS without comparable facilities, exporting both euros and data gravity with every training run.

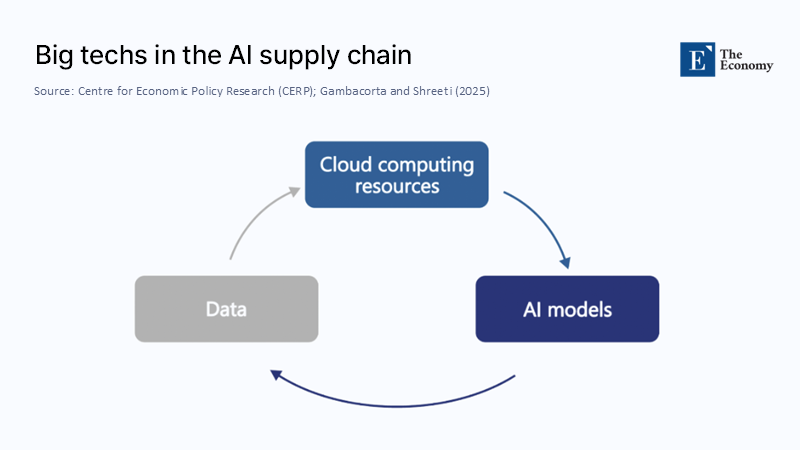

Figure 2 illustrates the feedback loop that now defines the industry. Data feed cloud; cloud trains models; models generate new data that further enrich cloud platforms. The flywheel is powered by scale economics Europe does not currently possess, and by permissive regulatory sandboxes the continent has not yet created.

Capital Flight, Talent Drift and the Silence of the Clusters

Money follows certainty, but not the kind supplied by 140-page conformity checklists. By the fourth quarter of 2024, European institutional investors devoted just 9% of their venture allocation to AI, compared with 28% in the U.S., according to Dealroom. Recruiters tell a complementary story: LinkedIn's 2024 AI in the EU study finds that AI specialists make up a scant 0.41% of the EU workforce, barely half the density in Silicon Valley. Even more troubling is flow rather than stock: senior machine-learning engineers who cut their teeth at German auto OEMs or French fintechs are decamping to Austin, Dubai, and Singapore, chasing unfettered access to cutting-edge chips.

That exodus has macro consequences. Each departing principal scientist drags an average of $ 3 million in follow-on venture capital, accelerating the relocation of adjacent roles—product, compliance, design—to satellite offices outside the Single Market. Talent, in other words, arbitrages regulation just as capital does.

Big Tech's Tactical Retreat: Europe as a Launch-Later Zone

Meta's decision to withhold its multimodal Llama release from EU users last July was dismissed by some Brussels insiders as brinkmanship. Nine months on, it looks like phase one of a broader strategy: de-prioritise Europe until the jurisprudence around the AI Act and DMA settles. Reuters captured the mood when Mark Zuckerberg and Spotify's Daniel Ek publicly warned that fragmented rules "risk forcing Europeans to rely on non-European AI technologies." The statement was less a threat than a descriptive statistic: consumer features can be geo-fenced, but training clusters and model weights are inherently global. They will anchor where the friction is lowest.

The fallout is acute for European SMEs. When OpenAI, Anthropic, or Google delay deployment, start-ups that build value-added layers—vertical fine-tunes, domain adapters, safety wrappers—find themselves waiting for a train that never arrives. Opportunity cost replaces fines as the hidden tax of first-wave regulation.

What Have Regulators Learned? Early Signals of the Second Wave

Contrary to caricature, Brussels is not deaf to market signals. Internal Commission memos acknowledge that a one-size-fits-all quality-management regime may "disproportionately burden micro-enterprises without commensurate risk reduction." Several amendments already on the table would tier documentation and testing obligations by turnover and compute intensity, narrowing the scope of ex-ante authorisation. Meanwhile, Washington's Commerce Department is drafting compute-threshold reporting rules that mirror the export-control logic applied to semiconductors—security first, commercial risk later.

The likelihood of convergence, therefore, hinges on timing. If the EU trims red tape faster than the U.S. moves toward pre-clearance, a hybrid model could emerge: the EU adopts outcome-based standards and sandboxing, the U.S. layers targeted disclosure on top of tort law. If both sides double down on their instincts—Europe on ex-ante permissioning, America on laissez-faire liability—the divergence will calcify, and capital will arbitrage accordingly.

Two Plausible Futures, 2026-2030

Managed Alignment

Europe builds three publicly subsidised, 100-exaflop sovereign clouds open to accredited researchers and start-ups and indexed to green-energy capacity. Compliance is scaled: founders with fewer than fifty employees file a six-page risk plan instead of a complete technical dossier. Venture funding recovers to $ 20 billion annually in AI, closing the gap with the U.S. to single digits by 2030.

Fragmented Tug-of-War

Member states tack national add-ons onto the AI Act, resurrecting the patchwork that GDPR was meant to end. Simultaneously, the U.S. fractures into fifty privacy codes, and China doubles down on data localisation. Foundation models balkanise, consumer prices rise, and productivity gains diffuse at half the rate predicted by OECD baseline scenarios. The analogy is the interwar tariff spiral—only this time, the tariff is compliance latency.

A Policy Playbook for Compute Sovereignty

If Europe wishes to escape the second scenario, three interventions are non-negotiable. First, computing should be treated as critical infrastructure; co-investing €12 billion in continental exaflop clusters would cost less than 2% of the NextGenerationEU fund and unlock domestic model training. Second, shift from prescriptive to outcomes-based regulation: certify transparency dashboards and red-team results, not static model cards. Third, tiered compliance should be adopted so that a garage founder in Porto does not fill the same annexes as a trillion-dollar incumbent.

Compute subsidies may offend purists, but they are strategically cheaper than watching every European unicorn pay a perpetual cloud rent to Seattle or Santa Clara. Tiered compliance aligns with subsidiarity: regulate risk where it resides, and focus enforcement on systemically important deployers, not experimental code on a laptop.

From Defensive Exceptionalism to Strategic Competence

Europe's first wave of AI legislation enshrined values the world admires; its second wave must prove those values are economically sustainable. The lesson of the past five years is blunt: a region can export standards only if it still exports products. Re-anchoring investment, talent, and compute inside the Single Market will demand a pivot from defensive exceptionalism to strategic competence—less pamphlet, more prototype. Therefore, the choice now confronting policy-makers is not protection versus innovation; it is whether protection can be engineered to enable innovation rather than ration it.

Europe has written many rulebooks; the time has come to build the press that prints them, or risk reading others' editions instead.

The original article was authored by Leonardo Gambacorta and Vatsala Shreeti. The English version of the article, titled "Big techs’ AI empire,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.