Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

The epicenter of African development financing is drifting eastward, just as Washington slams its doors shut. That single fact, understated in diplomatic dispatches but unmistakable in the balance-sheet figures, frames a policy moment in which China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is no longer merely competing with Western aid models; it is quietly inheriting the space those models are vacating. Beijing's evolving "global vision," captured by East Asia Forum's recent commentary on the continent, finds practical traction in Africa precisely because US policy has turned inward, hollowing out USAID's operational reach. The question is not whether Chinese capital can replace American grants dollar for dollar, but whether Beijing's state-directed soft-power apparatus can replicate the credibility, governance safeguards, and normative appeal once embedded in US programs.

A ledger written in renminbi: complex numbers behind soft power

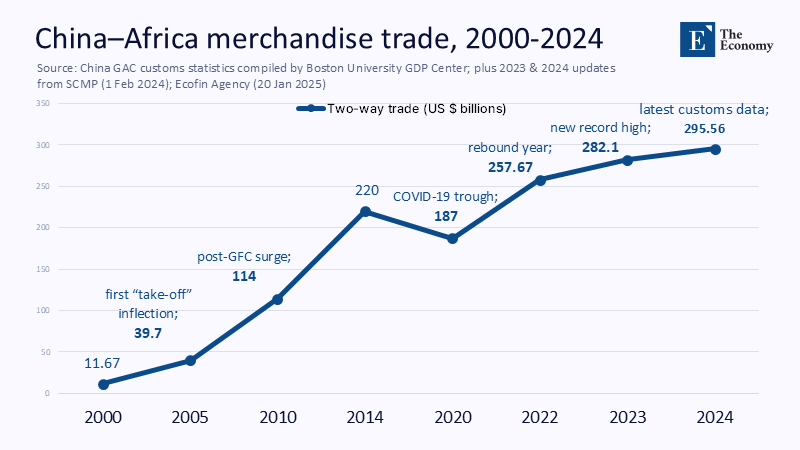

Over two decades, Sino-African trade ballooned from US $ 11.67 billion to US $ 257.67 billion, vaulting China past every Western partner as the continent's largest trading counterpart and fixing Beijing as gatekeeper to roughly 24% of Africa's external commerce by 2024. Figure 1, below, traces that rise in long perspective, underscoring the inflection points in 2005, 2010, and again in the post-pandemic rebound.

Total goods trade jumped from US $ 11.7 bn to almost US $ 296 bn in 24 years, with clear step-changes in 2005 (resource super-cycle), 2010 (post-GFC boom) and the post-COVID rebound after 2020.

In parallel, Chinese companies announced more than US $112 billion in green-field investment between 2000 and 2022. They closed US $24.6 billion in mergers and acquisitions, tilting Africa's industrial growth trajectory toward Chinese supply chains. The BRI, long criticized in Washington as debt-trap diplomacy, has evolved into a finance matrix that delivered US $ 21.7 billion in fresh African deals in 2023 and surged again to roughly US $ 29 billion in construction contracts last year—a 34% annual jump even as concessional lending elsewhere cooled. When Brand Finance ranked global soft-power footprints in 2024, China posted the most significant year-on-year gain, reaching third place behind the United States and the United Kingdom. The numbers speak a policy language: capital plus political narrative equal’s leverage.

The American vacuum: when aid turns discretionary, influence turns optional

Contrast those figures with the steep contraction in US development outlays. The Trump administration's executive freeze on 20 January suspended roughly 90% of USAID's planned 2025 budget, shuttered the agency's public website, and scattered thousands of field contracts. By March, analysts at Munich's MPRA estimated that 83% of Africa-bound grants had vanished. Food valued at nearly US $ 100 million now sits in Djibouti and Durban warehouses, destined for spoilage while 3.5 million people await rations. In Nigeria's conflict-scarred northeast, nutrition programs funded by USAID folded overnight; child mortality from acute malnutrition has already spiked. On the health front, PEPFAR's viral-load testing in South Africa collapsed by up to 21% after a US $ 439 million allocation stalled, threatening a reversal of two decades' gains against HIV.

The void is more than fiscal; it erodes decades of trust in American partnership and leaves African ministries scrambling for substitute finance, often with Beijing as lender of last resort. This erosion of trust is a significant consequence of the US freeze, with far-reaching implications for African development and international relations.

Beijing's bid to occupy abandoned ground

Chinese strategists have demonstrated remarkable foresight in seizing the opportunity. AFRICOM Commander Gen. Michael Langley's testimony to Congress in April highlighted Beijing's efforts to replicate cancelled USAID programs, including PEPFAR's community-health architecture. While he questions China's ability to match the technical depth, the replication is underway. BRI 2.0 packages combine concessional loans with vaccine donations, digital-skills academies, and Mandarin-language broadcasting hubs. President Xi's 2024 summit unveiled US $ 50 billion in new funds and a range of media-training fellowships designed to cultivate a China-literate elite. Educational exchange is the soft-power conveyor: African enrolment in Chinese universities jumped from 49,000 in 2015 to more than 81,000 by 2018, making Africa the second-largest regional cohort and seeding thousands of future decision-makers fluent in Chinese commercial norms. On the airwaves, Beijing's CGTN Africa bureau in Nairobi broadcasts to 40 countries, framing infrastructure stories as win-win cooperation while downplaying debt or environmental risk.

Culture is not cement: limits of cash-driven persuasion.

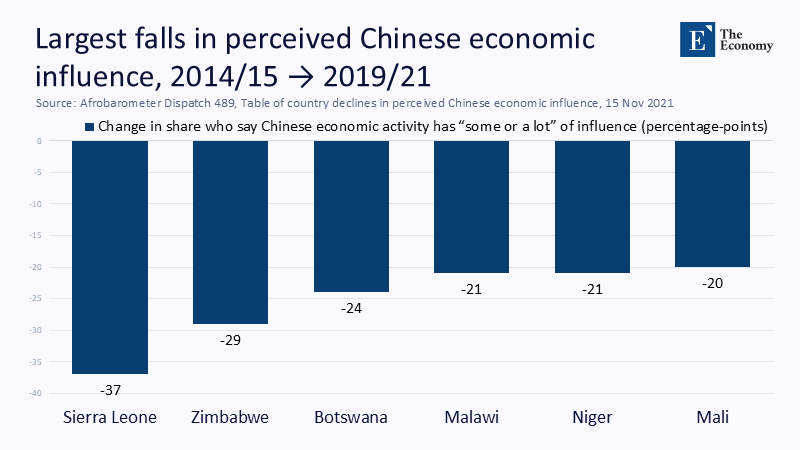

Yet the strategy's fault lines are widening. Afrobarometer's 2023 survey shows that 63% of Africans still view China's influence positively, down from the high-water mark registered five years earlier. Figure 2 illustrates the more dramatic slide in the share of citizens who say Chinese economic activity wields "some or a lot" of influence in their domestic economies, falling from 71% in 2014/15 to 59 % in 2019/21.

Chinese influence is slipping fastest in half-a-dozen African states. Sierra Leone leads with a 37-point plunge in citizens who think Chinese economic activity wields “some or a lot” of influence, followed by Zimbabwe (-29 pts) and Botswana (-24 pts) between the 2014/15 and 2019/21 Afrobarometer rounds.

The human costs of poorly regulated projects are no longer abstract. In February, a tailings dam at a Chinese-owned copper mine spilled 50 million litres of acidic waste into Zambia's Kafue River, forcing Kitwe's 700,000 residents off municipal water and killing fisheries along a 100-kilometre stretch. Such incidents undercut Beijing's green-development narrative and give weight to Langley's blunt assertion that he "couldn't name a single African country better off after partnering with China.

Debt sustainability, too, is entering a politically sensitive zone. From 2006 to 2021, Chinese loan pledges through the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation reached US $ 191 billion. Beijing's 2021 FOCAC commitment slashed credit lines by half, signalling caution amid growing African arrears. That retrenchment means some flagship BRI railways and power plants remain underused or stalled, complicating the narrative of seamless Chinese rescue. Meanwhile, sovereign lending for infrastructure is now at its lowest in twenty years, and the pivot toward mining concessions reinforces a perception that China is extracting strategic minerals more than building diversified African economies.

Quantifying the dependency trajectory

To assess the potential for African reliance on Chinese finance to surpass Anglo-Saxon aid within five years, consider a simple ratio of net official inflows. Using publicly reported commitments, Chinese infrastructure, mining, and energy contracts in Africa averaged about US $ 25 billion annually from 2022-24, while USAID's Sub-Saharan budget request for FY 2024 stood at US $ 8 billion, 73 % of which remains health-focused and now largely unfunded. If the current US freeze persists through 2026, cumulative USAID disbursements could shrink below US $ 4 billion per year—a level already overtaken almost six-to-one by Chinese lending. Using the BU Global Development Policy Center's historical series, an econometric projection of BRI engagements yields a compound annual growth rate of 8.4% since 2013; extrapolated, Chinese deals could top US $ 35 billion by 2027. Even if Beijing maintains its recent shift toward smaller, greener projects, the quantitative gap over shrinking US flows would still widen, raising significant concerns about African over-reliance on Chinese finance and the potential risks this poses for the continent's economic future.

Governance and the soft-power delta

Dollars alone, however, do not convert to soft power unless they align with recipient priorities and normative expectations. USAID programmes historically paired grants with civil-society capacity-building, anti-corruption benchmarks, and competitive procurement rules—features absent mainly from state-to-state Chinese deals. Ghanaian civil-society leader Bright Simons noted after the Kafue spill that "the cheque that built the dam came fast, but oversight arrived too late." The governance delta explains why African elites increasingly hedge: Kenya's National Treasury simultaneously courts Chinese and World Bank funding. At the same time, Zambia negotiates an IMF restructuring even as it approves new Chinese copper licenses.

Policy choices for African governments: strategic diversification

For African policymakers, therefore, the prudent course is diversification, not substitution. Leveraging the BRI's infrastructure finance need not preclude re-engaging a reformed US aid architecture—should Washington revive it—or inviting EU Global Gateway grants that explicitly target governance and climate-adaptation criteria. Structuring tenders that bundle local-content quotas, environmental bonding, and independent arbitration could harness Chinese engineering efficiency without mortgaging future fiscal space. Rwanda's 2024 green bond, underwritten partly by Beijing's Silk Road Fund yet certified by the London Stock Exchange, exemplifies the hybrid model.

A Western rethink: from moral hazard to credible partnership

For Washington and its allies, the lesson is stark. The credibility accrued through decades-long programs such as PEPFAR and Feed the Future dissipates far faster than it was built. Restoring influence will require more than budget line items; it demands predictable funding cycles insulated from partisan swings and aligned with African-led development plans. Public-private climate financing, university research consortia, and visa liberalization for African students could rebuild aspects of the value proposition that China still struggles to emulate.

Beyond zero-sum

The strategic narrative that pits Chinese largesse against Western retreat risks obscuring African actors' agency and the nuances of soft power. Beijing's ascent is real, numerically compelling, and, in many respects, filling a vacuum the United States created for itself. Yet the durability of that ascent depends on governance outcomes, environmental safeguards, and the cultural resonance of China's political model—areas where Beijing's record remains mixed. The United States, for its part, cannot win a race it refuses to run; reinstating functional development institutions is the precondition for any credible "values-based" counter-offer.

Thus, Africa's next decade will be shaped less by ideological allegiances than by pragmatic calculations of who can deliver infrastructure, jobs, and technology without drowning the continent in debt or toxins. The ledger may be written in renminbi for now, but the final balance of influence will be settled in the currency of trust.

The original article was authored by Samir Bhattacharya, an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. The English version, titled "Beijing's global vision takes shape in Africa," was published by East Asia Forum.