Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The quickest way to spot the firms that shrugged off the U.S.–China tariff wars is not to look at their purchasing departments but at their loan covenants. Companies that relied on lenders with deep roots across Asia rewired their inputs months faster, spent less on emergency inventory, and—most paradoxically—paid lower spreads for the privilege. In a decade now defined by geopolitical whiplash, a multinational bank’s information advantage has quietly become a substitute for physical capacity expansion. The thesis of this column is blunt: global branch networks are no longer a legacy cost centre; they are the critical plumbing through which real-time supplier intelligence travels, and capital markets still value them as if they were fading relics of 1990s globalisation.

The Geography of Decoupling—Seen from the Loading Dock

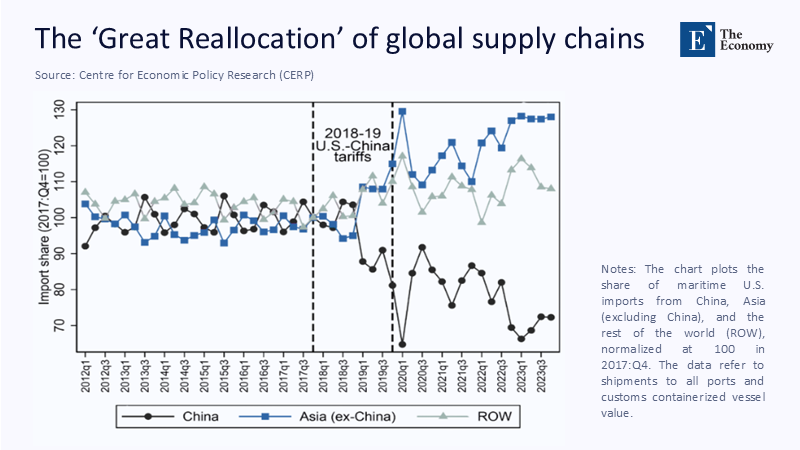

The figure above captures the rerouting of U.S. maritime imports better than any spreadsheet. China’s share, normalised to 2017-Q4, plunges after the 2018-19 tariff rounds and never claws back pre-trade-war levels, while “Asia (ex-China)”—mainly Vietnam, Thailand, and India—surges above the 120-index line. The rest of the world (ROW) holds roughly steady, indicating that the real contest for lost Chinese volume is being fought inside Asia.

The macro numbers corroborate the visual. China’s slice of total U.S. goods imports fell from a pre-war 21.6% in 2017 to just 13.9% in 2023, the lowest reading in two decades. Mexico and Canada are now the United States’ top goods suppliers. Still, the most dramatic relative gains belong to Vietnam, whose exports to the U.S. jumped to US$114 billion last year, up from US$69 billion in 2020. Decoupling, in other words, is not a thought experiment—it is visible in container decks and customs manifests.

When Liquidity Doubles as Cartography

Switching a core supplier is not like changing a cloud-storage vendor. Tooling certifications, test-lot inspections, and compliance audits often exceed three months even for standardised components. A 2024 McKinsey Global Institute study puts the average EBITDA loss from a one-to-two-month disruption at 30% of a normal year’s earnings for a consumer-goods manufacturer. The strategic problem is less about where to buy and more about who knows which alternate supplier is solvent, environmentally compliant, and capable of ramping volume next quarter, not next year.

That is precisely the due diligence corpus a trade-finance desk compiles whenever it opens a letter of credit. Balance sheets, port-throughput logs, FX exposures, ESG audits: these artefacts add to an institutional memory of cross-border solvency. The result is a form of industrial cartography that no logistics consultant can reproduce on a comparable cadence because the bank sees the cash flows first, not last.

Quantifying the Bank Premium—Evidence from the Tariff Shock

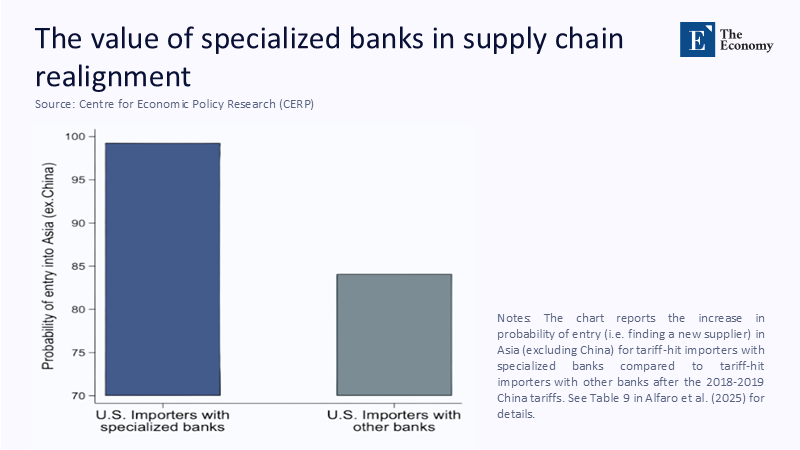

The figure below shows the punchline: tariff-exposed U.S. importers that banked with specialised lenders—defined as institutions with on-the-ground Asian trade desks—were roughly fifteen percentage points more likely to land a non-Chinese supplier in Asia after the 2018-19 tariff escalation than peers served by purely domestic banks.

Translate that lift into dollars. Assume a mid-sized electronics firm running a US$25 million annual throughput per plant. Shaving three months off a potential shutdown at a 26% gross margin preserves about US$1.6 million in earnings per site, often the difference between breakeven and a covenant breach. Multiply the same calculus across the roughly US$135 billion of U.S. imports that still relied on single-country sourcing in 2023, and the avoided EBITDA erosion surpasses US$4 billion.

Liquidity, Risk, and the Mirage of “Loose Credit”

Sceptics argue that faster credit inevitably means looser credit. The 2024 ICC Trade Register begs to differ: short-term trade-finance default rates remain below 0.20% across instruments, an order of magnitude lower than standard commercial lending. Information, not collateral, underwrites the risk; it is hard to default on a payment when the underlying cargo is visible in real time and the bank has already stress-tested the supplier’s ledger.

The spread of data is equally telling. Industry estimates put the average loan-pricing advantage enjoyed by firms with geography-specialised banks at 55-65 basis points during the 2020-23 rerouting frenzy. With aggregate emergency credit draws topping US$75 billion, that implied an interest-expense saving of roughly US$425 million—capital that many CFOs promptly recycled into dual-sourcing pilot runs.

Why Capital Markets Misprice Branch Networks

Yet all this informational leverage barely registers in equity valuations. McKinsey’s 2024 Global Banking Annual Review pegs the sector-wide price-to-book ratio at 0.9—the worst of any primary industry and a complete 40% below the long-run average for global banks. Analysts praise cost-income ratios and net-interest margins but seldom model the optionality in a 40-country trade-finance dossier. Meanwhile, the underlying product is compounding faster than GDP: the global supply-chain-finance (SCF) market, worth roughly US$7.6 billion in 2024, is projected to reach nearly US$17.4 billion by 2034 on an 8.7% CAGR.

The incongruity is glaring. Investors treat far-flung branch licenses as heavy overhead when, in practice, those very licenses mint alpha in the form of curated risk intelligence. The strategic conclusion is unambiguous: the next wave of bank multiple expansion will hinge less on net-interest-income surprises and more on monetizing supply-chain data exhaust.

Counting the Omitted Costs—Search, Certification, and Working-Capital Traps

Popular commentary often centres on tariff percentages, but the hidden killer is search cost. PwC’s 2023 Global Risk Survey reports that 71% of CEOs flag supply-chain disruption as a top-three risk, up from just 17% five years earlier. Internally, McKinsey calculates that certifying a new Tier-1 electronics supplier can eat up to 4% of annual procurement spend—a figure that tops US$2 million for the typical mid-cap manufacturer. Worse, the working-capital gap widens during the hunt: average days-payables-outstanding (DPO) shrinks by eight days because unproven vendors refuse long terms until trust is earned.

Banks with live counterparty files shortcut both pain points. Their credit officers already track vendor solvency ratios and port-handling capacity; they can pre-clear payment-term extensions, preventing a cash squeeze at precisely the moment a buyer is racking up expedited freight fees. The bank, in effect, subsidises the trust premium until the commercial relationship stabilises—a role that no government short-term subsidy has replicated with similar granularity.

Friend-shoring and the Policy Blind Spot

Washington’s “friend-shoring” doctrine is heavy on tax credits and light on financial plumbing. Tariff incentives may push an auto-parts plant from Shenzhen to Nuevo León. Still, without the credit lines and supplier audits that a cross-border bank provides, the move redistributes, rather than neutralises, operational risk. A pragmatic fix would be to make bank geographic specialisation eligible for Export-Import Bank guarantees or Development Finance Corporation risk-sharing. Europe faces the mirror image: its fragmented banking landscape lacks a pan-continental player with the coverage depth U.S. universal banks already wield—a structural gap Brussels could shrink by fast-tracking cross-border mergers under a resilience mandate.

Treating information as critical infrastructure is not a theoretical stretch. The U.S. already designates maritime port community systems as “systemically relevant”; extending similar status to trade-finance data pipelines would cost far less than subsidising bricks-and-mortar reshoring and yield a higher resilience multiplier.

What the Next Disruption Will Test

Run a stress-test scenario. Suppose a fresh geopolitical flashpoint forces another 5% of U.S. goods imports—about US$135 billion—to change country-of-origin in 2026. Based on Figure 2’s behavioural coefficients, firms with region-savvy banks would secure alternative suppliers three months sooner than firms without. Suppose the average plant carries 45 days of safety stock and earns a 26% gross margin. In that case, the uptime advantage translates into roughly US$4.2 billion in preserved gross profit, close to two-thirds of the entire annual budget of the Manufacturing Extension Partnership program. Add the documented interest-rate edge, and total financial savings crest US$4.6 billion. In blunt fiscal terms, underwriting bank intelligence would buy more resilience per taxpayer dollar than subsidising additional concrete boxes.

Updating the Metrics That Matter

Global supply chains are fragmenting, but information about them is consolidating—inside the compliance servers of well-networked banks. The market still discounts those servers as cost centres; policy makers still talk about reshoring warehouses while ignoring the credit lines that let a Southeast Asian vendor accept a 90-day term sheet on day one. The next decade will reward whoever corrects that mispricing first. That means re-rating the option value embedded in global branch licenses for investors. For governments, it means recognising that financial infrastructure is supply-chain infrastructure. And for corporate strategists, it means choosing lenders not only for balance-sheet heft but for the latticework of supplier intel they already possess. Capital, after all, now carries a map—and in a world of geopolitical detours, the firms that borrow the best maps will still be shipping when the next tariff wall goes up.

The original article was authored by Laura Alfaro, a Warren Alpert Professor of Business Administration at Harvard University, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Overcoming constraints: How banks helped US firms reroute their supply chains,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.