Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

Three degrees of annual temperature rise might feel like a meteorological footnote in the equatorial tropics, yet those extra degrees are rewriting Southeast Asia's growth formula. They lengthen air-conditioner duty cycles, bend electricity load curves upward, and—crucially—expose the region's chronic dependence on imported fossil power. International Energy Agency (IEA) modelling shows that ASEAN electricity demand will leap from today's 1,300 TWh to more than 2,000 TWh by 2035, at a compound pace faster than every bloc except India. The risk is not that these "young" economies lack the means to go green, but that youthful infrastructure will be shackled to ageing carbon assets before renewables scale. Sunlight that scorches rooftops 250 days a year and monsoon winds that tear across the Mekong basin are latent advantages worth trillions in avoided fuel imports. Whether those advantages become bankable depends less on physics than how policymakers choreograph a scramble for data-centre electrons, electric-vehicle (EV) gigafactories, and dispatchable back-up capacity.

The Silent Surge of Server Farms

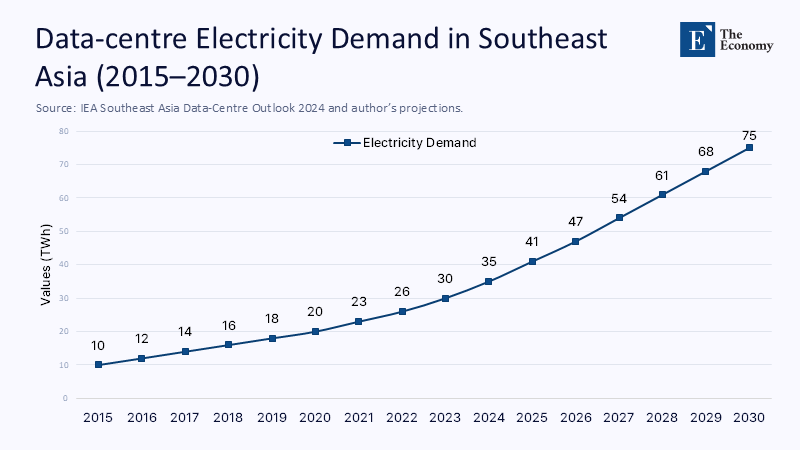

Investors talk about data centres in megawatts, but their social footprint is measured in terawatt-hours. Regional consulting work indicates Southeast Asia's installed data-centre capacity will nearly triple by 2027, adding roughly 2,100 MW of IT load to an existing base of about 1,200 MW. This surge in data-centre capacity will significantly increase the region's energy consumption. Assuming an 80% utilisation rate and a still-moderate power-usage-effectiveness (PUE) of 1.5, those new halls alone would gulp more than 22 TWh each year—roughly the 2024 electricity use of Myanmar's entire grid. Singapore's land-hungry hub-and-spoke model is already spilling into Johor and Batam, and Malaysia's pipeline—fuelled by Microsoft and AirTrunk approvals worth 80 MW in a single tranche—is projected to cross the two-gigawatt threshold by mid-decade. The IEA warns that regional data-centre demand could double again before 2030, mainly on the back of artificial-intelligence inference clusters housed in 70 kW server racks.

Unless power systems pivot decisively toward low-carbon supply, every teraflop processed in the cloud will hard-wire a tonne of CO₂ into ASEAN's ledgers, undermining newly minted net-zero pledges. If Singapore can already offset 10% of its grid emissions by importing Laotian hydropower, Indonesia, with twenty-two times the solar potential, has no structural excuse to let new server farms run on lignite.

EV Assembly Lines and the Nickel Dilemma

While racks of servers hum in climate-controlled vaults, a more visible industrial renaissance is taking shape on Southeast Asian factory floors. Thailand has lured US $1.4 billion of Chinese capital into EV plants led by BYD, Great Wall, and Changan; BYD alone aims to stamp 150,000 cars a year in Rayong, turning Toyota's petrol citadel into an export-oriented EV hub. Jakarta's response is Hyundai's fully integrated EV ecosystem, crowned by a 10 GWh battery-cell plant that taps Indonesia's abundant nickel laterites. However, this reliance on nickel for EV batteries presents a dilemma. Regional cell output stands at 16 GWh, yet pledged investments could triple that by 2030, vaulting Indonesia and the Philippines into the top tier of mined-nickel producers with two-thirds global output. While beneficial for the economy, this growth in nickel production also raises environmental concerns and underscores the region's need for sustainable mining practices.

The paradox is that every new gigafactory draws on the same stressed grids that serve homes and server farms. If EV production is powered by coal-heavy baseload, the cradle-to-gate carbon benefit narrows sharply, and the region's promise as a clean-mobility export base risks a reputational discount. A BYD sedan charged on Vietnam's average grid today emits 123 g CO₂-e/km—barely half the footprint of the petrol variant, but four times dirtier than an identical car plugged into a French socket. Therefore, the competitiveness of ASEAN's EV cluster rides on parallel progress in grid greening, not just on cheaper labour and critical-metal endowments.

Renewable Endowment versus Institutional Readiness

Nature is not the bottleneck. On a single August afternoon, the solar resource over the Javanese plains delivers 1,000 W per square metre, and Indonesia alone boasts 2,900 GW of technical solar potential—more than twenty times ASEAN's entire installed capacity. Wind, long considered peripheral, is now rewriting regional power geography. The 600 MW Monsoon Wind farm in Laos has already energised its 500 kV interconnector. It will sell clean power straight into Vietnam's north-central grid under a 25-year contract that broke new ground for cross-border renewables finance. This success story of the Monsoon Wind farm highlights the untapped potential of wind energy in the region and the opportunities it presents for sustainable energy development in Southeast Asia.

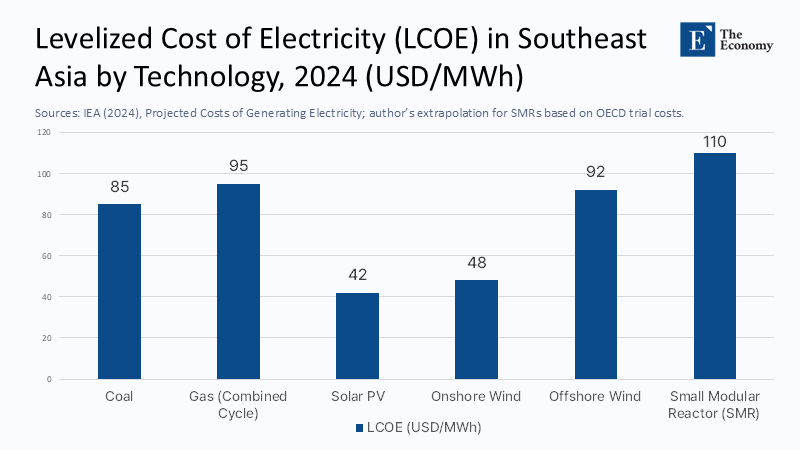

Malaysia's National Energy Transition Roadmap calls for 59 GW of solar by 2050, yet even that leaves the region short of the 229 GW of new solar and wind the IEA deems necessary by 2030 to align with a 1.5 °C pathway. The gap is not technical; it is transactional. Bankability hinges on land tenor, grid-connection queues, and tariff transparency—gaps that still favour gas-fired quick builds over utility-scale photovoltaics, even though new PV already lands below US $45 MWh across much of the archipelago.

The economic signal is unambiguous: every megawatt of PV or onshore Wind commissioned today undercuts new coal by at least US $40 MWh and beats even depreciated coal assets on marginal running cost once carbon prices exceed US $35 t⁻¹. Thus, the procurement lag is a policy failure, not a market verdict.

The Nuclear Option: Backbone or Costly Detour?

Energy planners seeking dispatchable, zero-carbon capacity inevitably circle back to fission. Indonesia's headline plan for twenty small modular reactors (SMRs) by 2036 would inject up to 13 GW of baseload into the ASEAN mix, potentially the region's first commercial atomic fleet. Vietnam has revived its shelved Ninh Thuận project, pitching it to European vendors even as Rosatom signs a technology roadmap in Hanoi. Yet the economics of first-of-a-kind SMRs remain untested outside temperate OECD markets, and the socio-political overhead—nuclear literacy, waste governance, non-proliferation compliance—could swamp budgets already strained by fossil-fuel-subsidy reform.

Figure 2 underscores the financial hurdle: SMR LCOE in Southeast Asia is projected at US $110 MWh—more than double the cost of solar and 40% above onshore Wind. Unless overnight capital costs can be compressed below US $4 000 kW⁻¹—a target even Idaho National Laboratory concedes is "aspirational"—the nuclear debate risks absorbing institutional bandwidth just when rapid-build renewables and grid-scale batteries could be deployed at scale for half the price.

Grid Integration and the Financial Engineering of Flexibility

Even perfect project pipelines will stall without wires. ASEAN utilities plan to lay more than 45,000 kilometres of high-voltage lines by 2030, but network investment must double to about US $22 billion a year to keep pace with load growth. The ASEAN Power Grid agreement—first penned in 2007—finally secured a landmark transaction when Singapore agreed to import 100 MW of hydropower-backed electrons from Laos via Thailand and Malaysia, effectively closing the first regional loop.

Such deals rely on contractual plumbing—virtual tolling agreements, cross-border wheeling charges, and imbalance markets—innovations now being replicated in battery-storage finance across Australia and, increasingly, the Greater Mekong. Flexible assets—four-hour lithium batteries, pumped hydro, and demand-response programs—are cheaper and faster to commission than SMRs, but only if they can earn capacity and ancillary revenues. Unlocking those income streams is less an engineering challenge than a regulatory one: open balancing markets, transparent curtailment rules, and tradable congestion rights.

Policy Compass: From Export Appetite to Social Contract

The scramble for electrons is already testing domestic political capital. Malaysia's 14.2% tariff hike forced Equinix to shop aggressively for renewable offtake contracts to protect margins on a pair of data centres that draw 7.2 MW—a preview of the tension between industrial policy and consumer bills. In Thailand, the Board of Investment now ties import privileges to local-content EV quotas, encouraging capacity but also risking oversupply and a bruising price war that could spill into labour markets.

Policymakers must pivot from a tired "green versus growth" narrative toward a portfolio logic that internalises risk. Three reforms would move the needle fast:

- Dynamic tariffs: Time-of-use pricing smooths peak loads and rewards flexibility, slashing the hidden subsidy to inflexible baseload.

- Grid-priority auctions: Connection rights auctioned to projects paired with storage, not simply to the lowest-cost generator, would accelerate dispatchable renewables.

- Just-transition trust funds: Earmarking a slice of carbon revenues to underwrite skills-upskilling in coal-mining regions preserves political capital while expanding the labour pool for renewables construction.

The credibility of that social contract will decide whether foreign investors interpret ASEAN's net-zero timelines as investable milestones or aspirational footnotes.

A Learning Laboratory for the Global South

What emerges is a story of choreography rather than constraint. Southeast Asia's perceived economic youth is not a handicap but a window in which energy-intensive industries are still malleable and infrastructure trajectories can bend greenward before they ossify. The convergence of data-centre demand, EV manufacturing, and decarbonisation targets creates a policy crucible that will instruct dozens of emerging economies wrestling with identical dilemmas a decade from now.

If Bangkok's next gigawatt of peak load is met by Laotian Wind instead of Indonesian coal, and if Jakarta's nickel-rich EV supply chain can certify renewable provenance to European showrooms, the region will have demonstrated that late-industrialising markets need not replay the twentieth-century fossil script. That outcome will hinge on whether ASEAN power pools accelerate faster than tariff politics, whether SMR rhetoric catalyses or crowds out capital, and whether the irresistible force of digital growth is matched by an equally dynamic embrace of monsoon winds and midday photons. The upside is incalculable: a generation of citizens who log on, plug in, and move about on kilowatts harvested from the climate that once menaced their prosperity.

The original article was authored by Yunkang Liu and Fengshi Wu. The English version, titled "Australia and China can power up Southeast Asia’s green energy transition," was published by East Asia Forum.