Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

From a distance, the red ink in America's current account may seem like a self-inflicted wound; however, a closer look reveals the US's pivotal role in dictating the global exchange rate. Fresh evidence from Hou, Sarno, and Ye's network model of trade imbalance centrality underscores that what truly matters for currency pricing is not the size of any single deficit but its position in the web of global flows. The United States, as the hub of that web, effectively sets the going rate for foreign-exchange insurance, turning a macroeconomic shortfall into a geostrategic asset. Any attempts to eliminate the deficit without replacing the lost connectivity risk raising, not lowering, America's cost of capital. This is the modern manifestation of the Triffin dilemma and the blind spot in today's tariff politics.

The geometry of deficits: centrality as currency collateral

Hou, Sarno, and Ye graft a Leontief-inverse measure of network centrality onto Gabaix-Maggiori's intermediary-based asset-pricing framework and then take the hybrid to 41 currencies between 1995 and 2021. In their data, a one-standard-deviation rise in centrality-based characteristic (CBC) lifts the required annualised risk premium by roughly 120 basis points, an effect that swamps the signal from traditional bilateral trade gaps. Put differently, centrality is a form of collateral: the more pivotal a country's trade links, the lower the bribe it must pay investors to hold its currency.

For the United States, that collateral remains abundant. The latest IMF COFER release shows the dollar's share of disclosed reserves edging to 57.8% in the fourth quarter of 2024, even as aggregate reserves shrank 3%. BIS cross-border data put outstanding dollar-credit to non-US borrowers at $13.2 trillion, more than twice the scale of euro liabilities. And the Bureau of Economic Analysis confirms that the current-account deficit widened to $1.13 trillion last year, 3.9% of GDP, without denting the broad dollar index. The pattern is consistent with the model: the larger the outward flow of dollars, the more the rest of the world must hold them, reinforcing the centre's bargaining power.

When network mathematics meets market returns

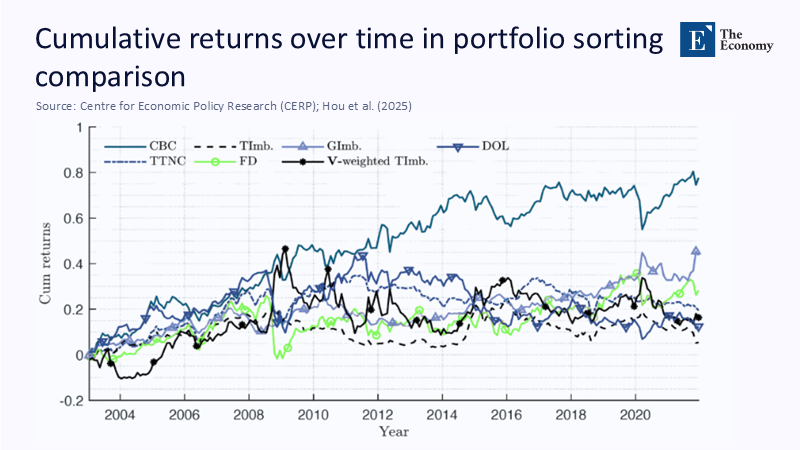

Theory meets reality in the market data. When currencies are sorted by the CBC metric and a zero-cost long–short portfolio is held, a Sharpe ratio 0.65 is earned over 2003-2021. This outperforms classic carry trades and dollar-centred strategies. Figure 1 visually represents this result: the blue CBC line consistently outperforms other portfolios, particularly after the global financial crisis.

The outperformance is more than a statistical curiosity. A variance decomposition in the same paper attributes almost 70% of the risk premium spread to neighbourhood effects—the ripple from one country's balance-sheet stress through its counterparties—underscoring the idea that the system, not the node, prices currency insurance.

Re-reading Triffin through a graph-theory lens

Robert Triffin's 1959 warning was stark: the issuer of the reserve asset must run a persistent deficit or choke off the very liquidity that anchors the system. Sixty-five years on, Hou–Sarno–Ye generalise the logic. It is not just the volume of the deficit that matters, but its map coordinates inside the global network. Downgrade the node's centrality, and every edge must reprice. That insight reconciles two long-standing puzzles: why the United States can sustain a negative net-investment position of $18 trillion yet borrow at lower yields than most surplus countries, and why efforts to force a surplus, rather than easing the burden, could raise funding costs by diluting the dollar's collateral value.

Investment strategists are already quantifying the trade-off. A recent Janus Henderson brief estimates that eliminating the goods deficit via across-the-board tariffs could subtract up to one percentage point from long-run GDP growth. This is due to the weakening of the dollar's safe-asset status and the subsequent reduction in foreign demand for Treasuries. The model developed by Hou–Sarno–Ye translates this intuition into risk-premium language: a two-point drop in the United States' CBC score—a plausible outcome if trade is forcibly re-routed—would lift the forward premium on the dollar by roughly 20 basis points, or about $60 billion a year in extra federal interest expense at today's debt levels.

Tariffs as self-inflicted network shocks

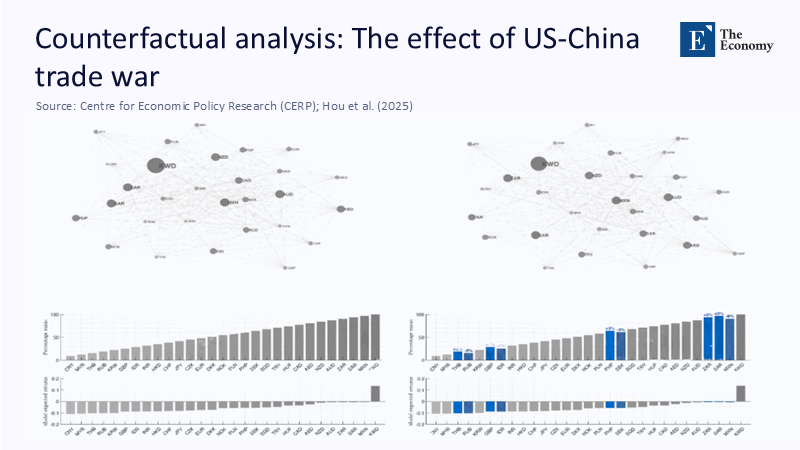

Despite the potential negative impact, tariff revivalists are undeterred. Former president Donald Trump's advisers are on record favouring a uniform ten-per-cent import levy, with a 60-per-cent penalty rate on Chinese goods. Private-sector modelling for the National Retail Federation suggests the proposal would slash consumer surplus by $78 billion and cascade through supply chains in ways that statistical agencies could not fully trace for years. The CEPR team offers a clearer, real-time picture: they feed a simulated US–China trade war into their network and watch the edges redraw themselves.

Figure 2 sketches the outcome. When bilateral trade costs rise, peripheral nodes divert flows through secondary hubs, shrinking America's relative centrality and pushing the required premium on the dollar higher in the model's equilibrium. The bright blue bars in the lower right-hand panel show the jump in expected returns to long-CBC portfolios accompanying the post-tariff topology.

The political slogan that tariffs will "shrink the deficit" is, in network terms, an expensive gamble. Yes, the shortfall of goods might narrow, but the system would then demand a fatter spread to finance the still-massive US fiscal deficit, neutralising any ostensible savings. The model's arithmetic is unforgiving: Reduce the current-account gap by $250 billion, and the present value of the Treasury's interest bill could climb by half that amount within a decade because the currency premium has repriced. The Treasury would swap a visible import bill for an invisible tax on every future bond auction.

Liquidity, leverage, and the quiet subsidy

The dollar's central role also subsidises US financial intermediation in less apparent ways. First, foreign exchange swap markets routinely clear on a cross-currency basis that favours dollar lenders, allowing US banks to raise euros or yen more cheaply than European or Japanese banks can raise dollars. Second, insurance companies and pension funds worldwide treat Treasuries as the baseline collateral for regulatory purposes; any impairment of that collateral—say, through a weaker reserve-asset status—would force global institutions to hold more capital or pay higher margins. That hidden cost would feed back into US funding markets through higher bid–off spreads.

BIS researchers estimate that a 50-basis-point widening in average cross-currency swap spreads reduces global leverage by three to five percentage points, enough to shave half a point off world GDP in the following year. In other words, tampering with the network's hub does not merely punish the United States; it slows the entire system, raising the odds that the next shock will come sooner and hit harder.

Policy implications: manage, don't eradicate, the deficit

If the deficit is the entrance fee to the central node, the policy task is to keep the cost affordable and productive. Several concrete steps flow from that premise.

First, the composition of imports should shift away from low value-added consumer goods toward innovation-dense inputs—advanced semiconductors, specialised machinery, intellectual property royalties—that raise domestic productivity and, therefore, the income base that services the external gap. Second, broaden the menu of safe dollar assets. For example, a deeper market for tax-exempt infrastructure bonds would soak up foreign savings without crowding out Treasury demand. Third, the Federal Reserve's swap-line network should be expanded beyond the current cohort of advanced-economy central banks; doing so would lower the system-wide shadow cost of dollar liquidity and, therefore, the risk premium implicit in CBC spreads. Finally, anchor the fiscal outlook with a multiyear primary-balance target. The CEPR model holds asset supplies constant, but a ballooning federal deficit can overwhelm a central node's collateral edge.

None of these measures entails throttling the flow of goods or the circulation of dollars; instead, they recognise that the flow itself is the substrate of monetary power. The goal is not to defy Triffin by turning red ink black, but to honour the dilemma by ensuring the ink pays for privilege rather than indulgence.

Power that earns its rent

Reserve currencies have always carried what Charles Kindleberger called the "burden of responsibility": they must supply the liquidity and rules that knit the world economy together. Sterling performed that role in the nineteenth century until Britain's export and capital flows could no longer match the scale of global commerce. The dollar has worn the mantle since 1945 precisely because the United States absorbed imports, exported safe assets, and, crucially, sat at the centre of a web that let others hedge the resulting exposures in deep, elastic markets. Hou, Sarno, and Ye give the intuition mathematical bones: centrality, not size, is the actual coin of the realm, and trade deficits are the seigniorage that mints it.

To treat the deficit as mere waste to be eliminated is to misunderstand what the United States sells to the world. Foreigners buy not just soybeans, software, or securities but a multidimensional insurance contract priced in dollars. Close the tap, and the premium on that insurance must rise, with the bill landing ultimately on the US taxpayer. Keep the tap open but channel it into higher-return domestic uses, and the very imbalance that unsettles headline writers becomes an under-researched source of advantage.

The honest debate, then, is not whether America should run a deficit—Triffin answered that—but how to maximise the return on the dollars that deficit sets in motion. Until tariff advocates engage with that arithmetic, their programme risks becoming what the CEPR model already predicts: an own goal scored on the balance sheet of the currency they claim to defend.

The original article was authored by Ai Jun Hou, a Professor of Finance at Stockholm University, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "The trade imbalance network and currency fluctuations," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.