Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

A single sentence captures the inflection point: in 2024, for every new dollar of long-term credit Chinese banks extended to emerging and developing economies (EMDEs), Chinese companies put almost two dollars of equity on the ground. That inversion of the traditional Belt and Road (BRI) funding mix is not bookkeeping trivia; it is the clearest market signal yet that Beijing now values the strategic flexibility of corporate ownership above the leverage of sovereign debt.

Anticipating the Future: China's Transition from Debt to Equity in Development Finance

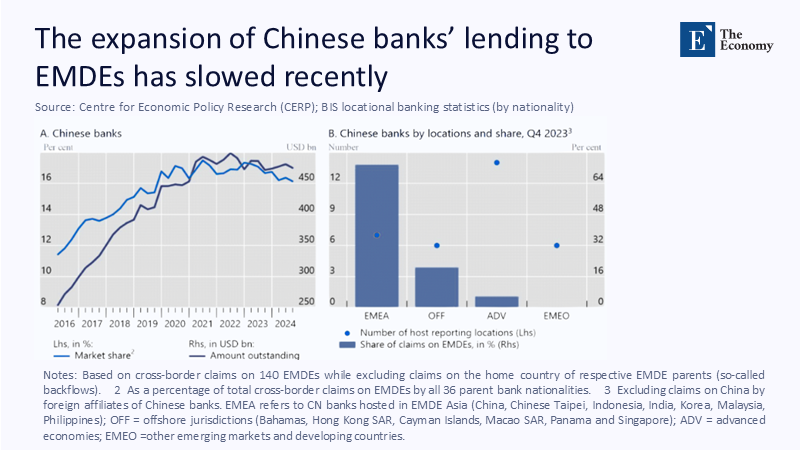

Over the past two decades, China's policy banks—chiefly the Export-Import Bank of China and China Development Bank—supplied the world's fastest-growing pool of bilateral credit. Between 2016 and 2019, their cross-border claims on EMDEs swelled from roughly USD 270 billion to just over USD 430 billion, lifting their market share from 11% to 16%. The pandemic froze that momentum. BIS data show the outstanding stock of claims on EMDE borrowers plateauing and even drifting lower in 2023 and 2024, while the share of global EMDE lending by Chinese banks stalled at the high-teens. As Beijing's credit engine downshifted, its outward direct investment (ODI) surged: according to EY's 2024 overview, total ODI reached USD 162.8 billion, up 10% year-on-year, with non-financial flows jumping 11%.

The visual clarifies what balance-sheet summaries can obscure: Chinese banks no longer sprint ahead of their OECD counterparts. Instead, they are treading water while Chinese corporates sprint into factories, lithium pits, solar glass plants, and data centers. BIS researchers document a decisive break in the data-generating process: before 2020, Chinese lending to EMDEs followed the curve of bilateral trade; after 2020, it hugs the trajectory of Chinese outward FDI. That finding corroborates field evidence—Brazilian EV assemblies, Hungarian battery gigafactories, Indonesian nickel refineries—where the capital stack, a term used to describe the composition of a company's capital structure, is equity-led and bank-loan-light, indicating a shift in the financing structure of these projects.

Data-Grounded Evidence of the Pivot

The economy-wide aggregates tell only part of the story. AidData's rescue-loan tracker counts USD 240 billion in short-term bailout finance—swap lines, rollovers, and bridge loans—channeled to 22 debtor governments between 2016 and 2021. That mushrooming "lender-of-last-resort" role suggests Beijing capped new risk-weighted assets on bank balance sheets by recycling maturing exposures instead of expanding them. Conversely, ODI flows concentrate in sectors where upside volatility can compensate for headline exposure. Rhodium Group notes that clean-tech supply chains alone absorbed more than USD 100 billion in fresh commitments since 2023, with nearly four-fifths of new Chinese green-field spending landing in energy transition metals, batteries, and EV platforms.

The numerical symmetry is striking. Ministry of Commerce statistics put China's 2023 ODI at RMB 1.04 trillion—about USD 148 billion—and early 2025 press briefings confirm a further 10% rise in 2024. In other words, the annual equity flow now exceeds the net increase in EMDE loan exposure by a factor of three. The portfolio view matches the country view: Reuters reports that sovereign lending for African infrastructure sits at its lowest in two decades, even as new Chinese investment in African mining jumped 114% last year.

Geopolitical Implications of the Balance Sheet

Why the sudden preference for equity? The usual macroeconomics of a maturing surplus economy explains part of it. As a surplus economy matures, domestic marginal returns on capital tend to slip below plausible overseas returns. This economic trend, similar to the yen appreciation that nudged Japanese savings outward in the late 1980s, is nudging Chinese capital abroad. Yet the sharper edge is geopolitical. U.S.-led technology export controls, secondary sanctions, and tariff walls raise the transaction cost of arm's-length trade and dollar-denominated financing. By buying the factory outright—whether a cathode plant in Debrecen or a solar-glass line in São Paulo—Chinese firms can route cash flows through local banking systems, thereby muting sanction risk.

The BIS working-paper authors find no evidence that countries hit by Western financial sanctions attracted more Chinese bank lending. Still, they did attract more Chinese equity, suggesting a conscious policy of substituting politically visible credit with quieter ownership stakes. Beyond sanctions evasion, direct ownership delivers supply-chain security. If Indonesian export quotas squeeze nickel hydroxide shipments, a Chinese battery maker owning the smelter has standing in Jakarta and the court system rather than a frustrated offtake contract.

Risk Migration and Governance Challenges

Shifting from creditor to shareholder does not eliminate risk; it rearranges who bears which part of the distribution. When the instrument is a sovereign loan collateralised by tax revenue, default risk sits with the borrower. All partners accrue cash-flow volatility, regulatory fines, or labor unrest in an equity joint venture. The BIS data set underscores this trade-off: while Chinese banks still lead lending to more than sixty EMDEs, the average recipient's public-debt-to-GDP ratio has climbed, and the median sovereign rating slipped a notch in 2023 compared with the pre-COVID level.

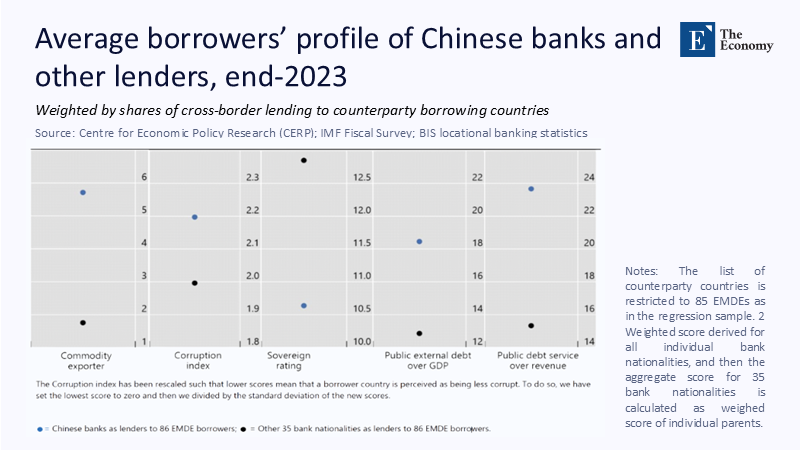

The scatterplot in Figure 2 lays bare two patterns. First, Chinese banks' loan books tilt toward commodity exporters—a legacy of oil-backed loans in Angola, copper-secured credit in Zambia, and coal-linked facilities in Pakistan. Second, their borrowers show lower sovereign-credit scores yet higher external-debt-service ratios than the global bank average, illustrating Beijing's willingness to lend where Basel-III-constrained peers shy away. Moving to equity does not reverse that preference for risky geographies; it merely aligns China's upside with the host's fortunes while diffusing political backlash over "debt traps."

For host governments, the governance arithmetic becomes harder. Joint-venture statutes replace loan covenants; ministries accustomed to negotiating grace periods must now master anti-dilution clauses and technology-licensing agreements. The risk that politically connected minority partners extract rents through transfer-pricing has already surfaced: a 2024 Brazilian labor-safety probe revealed undocumented service fees flowing from a Chinese EV-battery affiliate to a Hong Kong management company. Such episodes underscore that equity can embed external influence in corporate decision-making for decades beyond a loan's amortisation schedule.

Borrowers' Policy Toolbox: New Skills for a New Capital Structure

The immediate priority for EMDE policymakers is upgrading their negotiation toolkit. Whereas debt workouts once revolved around Net Present Value (NPV) calculations and Paris-Club comparators, equity deals require expertise in shareholder-agreement drafting, dividend-block thresholds, and arbitration-seat selection. Governments that fail to adapt risk ceding disproportionate control over critical minerals or strategic infrastructure. Kenya's National Treasury, for instance, discovered in 2023 that a 49-percent Chinese stake in its first 5G data-center venture carried a super-majority veto over data-localisation policies. This arrangement would have been impossible under a secured-loan framework.

Therefore, capacity building must broaden. Multilateral lenders and regional development banks should condition technical assistance packages on creating sovereign equity-evaluation units, mirroring the debt-management offices that flourished after the 1990s Brady-bond restructurings. Without such units, recipient countries will lack the analytical horsepower to vet China-proposed shareholder loans, vote on reinvestment versus dividend distribution, or adjust board composition to reflect changes in country risk.

Western Strategic Response: Competing on the Cap Table

For Washington and Brussels, countering Beijing's new-look statecraft demands their pivot. Merely rolling out larger credit lines—whether via the G7's Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) or the U.S. Development Finance Corporation—addresses yesterday's mode of influence. The competitive arena has moved to convertible-preference shares, offtake-linked equity, and local-currency project finance. Building a matched offer set will require blending public guarantees with private equity funds, expanding the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) capacity, and tweaking OECD Export Credit Agency rules to allow higher-risk tranches in strategic minerals.

There is also a security-tech dimension. Direct Chinese ownership of data centers, subsea-cable landing stations, or satellite-ground segments in EMDEs creates a surface area for intelligence collection and network-standard setting. Treating these as purely commercial stakes underestimates their strategic utility. A fuller Western response would package equity capital with transparent governance covenants, open-data requirements, and security audits—moving away from the binary framing of "good loans versus bad loans" toward a subtler contest over corporate-control rights.

Implications for the Classroom and the Think Tank

The pedagogical fallout is significant. Development-finance syllabi that stop at sovereign-bond analytics now risk obsolescence. Courses must integrate modules on cross-border M&A law, joint-venture governance, and the political economy of corporate control. Quantitative assignments can use BIS loan data and UNCTAD FDI statistics to illustrate how a one-standard-deviation rise in Chinese ODI affects a borrower's liability structure and current-account balance. The policy-research community needs new metrics: instead of ranking countries by Chinese debt stock alone, scholars should track effective equity influence—board seats held, dividend repatriation clauses, and supply-chain criticality scores.

The upshot is a richer, more complex research agenda. Where earlier debates fixated on the morality of Chinese lending terms, the new question is how equity changes the calculus of influence and dependency. That agenda blends corporate-finance analytics with classic diplomatic theory—precisely the interdisciplinary terrain future development economists and international relations scholars must navigate.

Teaching the New Grammar of Sovereign Capital

China's decision to swap the creditor's chair for the shareholder's seat is more than a tactical adjustment; the grammatical shift rewrites the sentences of global finance. By prioritising equity over debt, Beijing sidesteps the political costs of arrears, secures a durable claim on future cash flows, and embeds itself in the governance architecture of critical industries from lithium to cloud computing. For EMDE governments, the opportunity for Chinese investment remains real—jobs, infrastructure, technology—but the governance stakes are higher and the bargaining space is more crowded. For Western policymakers, the strategic game now unfolds not in Paris-Club conference rooms but in corporate boardrooms from Jakarta to Johannesburg.

Failing to perceive this shift courts analytical myopia. The world's leading bilateral financier has effectively redeployed its balance sheet to chase upside and manage downside through ownership, not liens—a move mirrored only once before, by Japan in the post-Plaza decade. The sooner educators, analysts, and negotiators internalise this new grammar of sovereign capital, the better prepared they will be to write policies that serve their publics rather than history's momentum. In development economics, as in language, mastery begins with recognising that the rules have changed.

The original article was authored by Cathérine Casanova, a Senior Economist at the Swiss National Bank, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Chinese banks and their EMDE borrowers," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.