Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

The instant Canberra wired its first US $500 million instalment to an American shipyard that has never built an Australian vessel, the romance of "mateship" dissolved into a line-item on the US Navy's capital-works spreadsheet. From that moment, the AUKUS compact stopped being a promise about shared values and became a cost centre measured against every new classroom, hospital wing, and research grant the Commonwealth will postpone to pay the bill. That single payment, followed by a pledge to tip in a total of US $3 billion to widen US slipways before a single Virginia-class submarine changes hands, is the signature of a strategic era in which Washington sells reassurance by the invoice and allies learn poker-faced arithmetic.

The Price-Tag Moment

Australia's sticker shock did not begin with the cheque; it started with the delivery timetable that transforms a headline number into household mathematics. Treasury now pegs the life-cycle cost of the nuclear-propelled submarine program at A $268 billion–A $368 billion by 2055, or roughly 0.15% of GDP annually for three decades. At current growth trajectories, that annual slice equals the combined operating grants of Australia's eight leading public universities or 80% of the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Defence Minister Richard Marles insists the outlay is "the cost of credibility." Yet, the fact that Canberra must pay US yard managers up front to guarantee production slots underscores a brutal asymmetry: strategic latency is Australia's, and industrial leverage is Washington's.

The domestic fiscal context is equally unforgiving. The 2024-25 defence budget climbs to A $55.7 billion (US $36.8 billion), nudging the defence-to-GDP ratio to 2.3% and signalling a glide-path to 2.5% by 2030. If the submarine invoice adheres to its upper band, boats alone will devour nearly one-eighth of that budget in the late 2030s. Therefore, every marginal tenth of a percentage point above 2.5% requires either a tax rise, deeper social-spending cuts, or heavier borrowing—all options that collide with Canberra's bipartisan promise to cap net debt below 40% of GDP. The submarine line item is not merely the largest defence project in national history; it is a macroeconomic constraint that narrows every subsequent choice the Treasury secretary will place before the cabinet.

Counting the Costs: Numbers That Bite

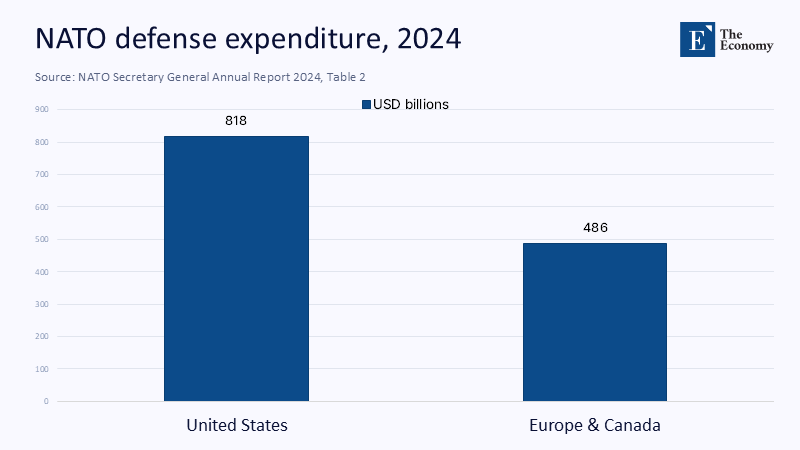

Washington's ask looks even starker when benchmarked against its burden-sharing rhetoric elsewhere. Within NATO, the United States currently bankrolls 64% of the Alliance's total military spend—US $818 billion of a 2024 tally of roughly US $1.3 trillion—while the rest of Europe plus Canada covers US $486 billion. Allies chafe at the imbalance, yet the imbalance at least flows in their favour. AUKUS, by contrast, reverses the polarity: Australia shoulders almost the entire cash transfer and still waits a decade for hulls. The numbers are so lopsided that analysts at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute now refer to AUKUS as "a reverse-premium insurance policy: you pay now to be insured later, but the insurer can redefine the policy wording mid-contract."

The visual juxtaposition clarifies what prose can blur: in the Atlantic theatre, Washington is the majority shareholder; in the Indo-Pacific, Canberra is the principal underwriter. Australians' uncomfortable deduction is that the greater their financial stake, the less contractual leverage they appear to wield.

Trump's Tariff Doctrine and the Economic Front Line

The submarine surcharge is only one face of America's emerging "invoice diplomacy." The other wears a tariff ledger. President Donald Trump's second-term trade doctrine, resurrected under the label "reciprocal rebalancing," hits allies first to prove resolve at home. A 25% tariff on Australian steel and aluminium remains in force, and a mid-March bill in the House Agriculture Committee seeks a 70% duty on Wagyu beef plus a spread of 2–10% levies on additional exports worth almost A $30 billion.

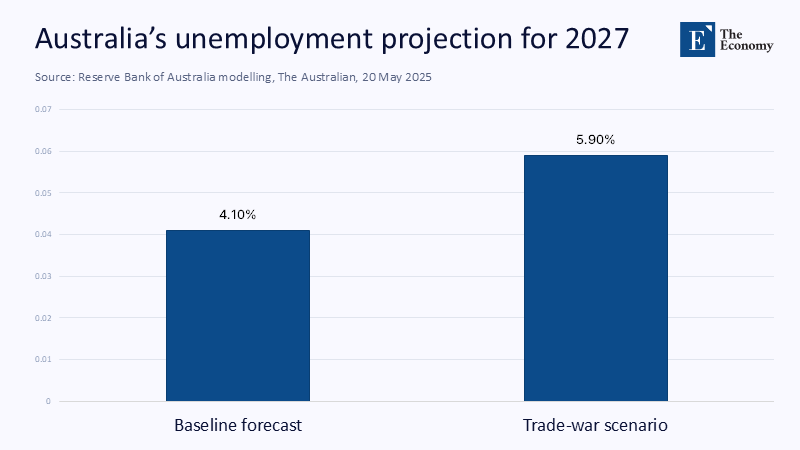

Reserve Bank modelling treats that proposal not as a bluff but as a baseline. Under the Bank's "trade-war" scenario, GDP growth slows by 0.7 percentage points, pushing unemployment from 4.1% to 5.9% by 2027 and erasing half the employment gains since the pandemic. The macro story converges with the micro: for every A $100 paid at a supermarket checkout, households would effectively transfer an extra A $1.60 to the federal government in lost real income by 2028—precisely the year the submarine program's domestic manufacturing ramp-up is due to peak.

The chart exposes a cruel symmetry: the more Australians pay for strategic hardware, the more vulnerable their pay packets become to the ally selling that hardware. In a combustible media environment, such arithmetic risks mutating into a betrayal narrative: "We fund your yards, you tax our exports."

Reading Europe's Playbook: NATO as Precedent

Canberra's anxiety intensifies when it scans the Atlantic horizon. In April, the US envoy to NATO reiterated a demand that European defence budgets migrate from the longstanding 2% pledge to "something closer to 5%" within the decade—a leap that would compel Germany alone almost to treble its military outlays. Paris and Berlin protested, but Washington's logic was arithmetically unassailable: the United States covers nearly two-thirds of current NATO defence spending even though it accounts for only 53% of Alliance GDP. The message to Europe doubles as a cautionary headline for Australia: sentimental allies must re-price their sentiment or insure themselves elsewhere.

The trend line is plain. Since 2016, every new US National Defense Authorization Act has included a chapter on "allied cost-sharing," sharpening the financial tools available to the president each year. AUKUS Pillar I—nuclear propulsion—looked exempt until the shipyard invoice turned a cost-plus contract into Canberra's problem. Pillar II—advanced capabilities—now appears just as contingent; congressional staff have floated amendments that would tie intellectual-property sharing to Australia's willingness to purchase additional hypersonic prototypes. The underlying operating theory is that American technological primacy is a tradable good, not a club good.

Public Sentiment and Political Feedback Loops

Australian voters have begun to smell the asymmetry. The Lowy Institute's March 2025 pre-election release reports that only 36% of Australians trust the United States "to act responsibly in the world," the lowest figure since polling began in 2005 and a 13-point slide in twelve months. The generational gradient is even starker: Under-35s register trust at 28%, undercutting the bipartisan assumption that US alignment is a civic article of faith.

That scepticism has an electoral bite. Labor strategists credit part of their current nine-point lead to a narrative that paints opposition leader Peter Dutton as "Trump-adjacent." The narrative resonates because the submarine-tariff duality supplies tangible evidence; it is no longer a culture-war slogan but a price that shows up on pay slips for coal miners and price labels for cattle exporters. Canberra's political class, therefore, confronts a structural dilemma: alliance costs that once lived in below-the-line ledger columns now campaign front and centre.

Hedging with Open Eyes: Policy Options Beyond Washington

Strategists answer uncertainty with options. The first option is regional multilateralism, which treats the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) as an economic and naval platform. Tokyo's plan to build an undersea cable ring linking Darwin to Okinawa, costing $4.6 billion, could open a Japanese supply-chain artery through which Australian rare-earth oxides travel north. In contrast, Japanese battery technology flows south, mutually reducing reliance on US electronics export controls.

The second option is targeted sovereign capability. Treasury modelling shows that a $18 billion investment over ten years in missile-defence interceptors and cyber-resilience utilities would deliver a deterrence coefficient—measured as adversary cost to attack per dollar of defender spend—three times higher than the initial decade of submarine amortisation. The calculus owes to the fact that sea-control assets remain latent until deployed, whereas space-and-cyber assets impose continuous uncertainty costs on an adversary.

The third is trade diversification. Two-way commerce with ASEAN reached a record $192.9 billion in FY 2023-24, already outstripping trade with the United States or Japan. Treasury modelling indicates that every 5% fall in US merchandise demand could offset a 1.1% rise in ASEAN demand at current elasticity. Viewed through that lens, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework might matter less than streamlined export-credit guarantees for Australian med-tech and agritech firms entering Indonesian and Vietnamese markets. Diversification is thus not anti-American; it is an insurance premium against tariff volatility in Washington.

A Curriculum for Strategic Literacy

For educators, the debate supplies a compelling interdisciplinary module. International relations students can be tasked with scenario-based cost-benefit matrices integrating defence expenditure, tariff exposure, and opinion-poll elasticity. Business schools might model supply-chain risk along alliance fault lines, quantifying how tariff escalators interact with shipping-insurance costs in a contested South China Sea. Political-science courses should trace how domestic constituencies rewrite Alliance narratives when economic pain localises, using Lowy polling trends as econometric inputs.

Quantitative fluency is indispensable. Assignments that allow undergraduates to project defence spending to 2055 under varying GDP growth bands reveal that a 0.3-point slowdown in annual growth lifts the AUKUS bill's share of GDP from 0.15% to 0.19%—enough to eclipse the federal research-infrastructure budget in the out-years. Such exercises humanise abstract billions and inoculate civic debate against the placebo of patriotic slogans.

Curricula must also teach the sociology of security. Lowy's data show widening generational divergence; equipping younger Australians to translate their security preferences into budgetary language is essential if public consent is to remain informed rather than nostalgic. The objective is not to produce reflexive scepticism but disciplined curiosity: the ability to ask, "What is the marginal deterrence effect per tax dollar?" every time a defence minister releases a talking-point slide deck.

From Sentiment to Audits

Washington's partial retreat from unlimited alliance underwriting is not tantamount to abandonment but is an undeniable invitation to audit. The emerging pattern—from NATO fee hikes to AUKUS surcharges—proves that alliances are no longer fixed-rate mortgages; they are variable-rate instruments that reset each electoral cycle. That shift does not render alliances obsolete; it makes them contingent on continuously defensible financial equilibrium.

Australia's rational response is neither to rage at betrayal nor to indulge in isolationist reverie. It is to treat alliance management as a rolling capital-budgeting exercise that weighs costs, returns, and substitutes in real time. This approach allows Canberra to retain the dividend of American technology and intelligence sharing while inoculating itself against fiscal or tariff shock.

In that light, the US $3 billion invoice for shipyard capacity is less an indignity than a diagnostic. It tells Australians exactly how Washington's new strategic business model works: friendship will be honoured, but only if the ledger stays black on both sides of the Pacific. Canberra can pay the bill, but it should never again sign it without reading—and, where necessary, renegotiating—the small print.

The original article was authored by John Quiggin, a Professor of Economics at the University of Queensland. The English version, titled "US–Australia alliance wanes under Washington’s whims," was published by East Asia Forum.