Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Before any theoretical discussion, a stark arithmetic truth sets the stage. For every hundred euros a euro-area multinational invests abroad, it reaps a meager fifty-five euros in profit compared to the hundred dollars earned by its North American counterpart. This significant disparity means Europe is earning less and missing out on a triple-digit billion dividend each year, with the gap only getting wider.

The Statistical Chasm

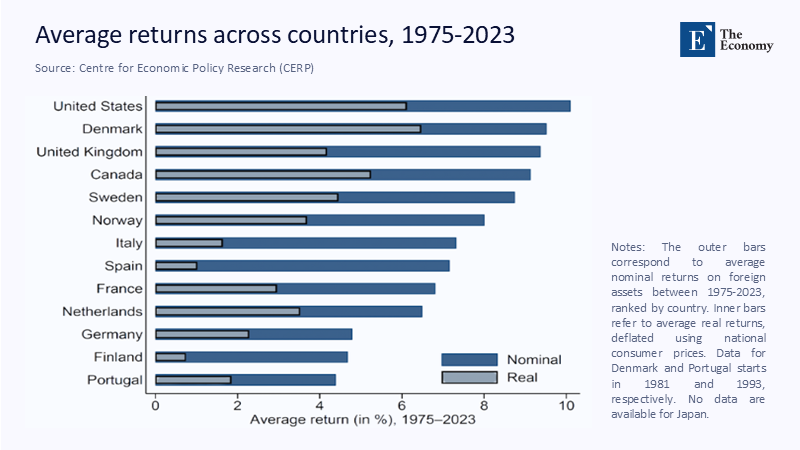

Figure 1 captures the raw scoreboard of almost half a century. The outer bars report nominal average returns on foreign assets between 1975 and 2023, and the paler inner bars convert those numbers into real purchasing power.

Denmark's improbable perch alongside the United States and Canada shows that northern Europe can, in theory, run with the alpha pack, but the rest of the euro area hugs the bottom of the ranking. In their most recent common year of data, the outward rate of return for the whole European Union crept back to 5.2%—its best showing since 2018, yet still a full 3.9 percentage points below the U.S. benchmark of 9.1%, a figure confirmed by the Bureau of Economic Analysis for 2022. When a gap that wide applies to an outward stock of €9.382 trillion—the amount Eurostat says EU investors hold overseas—the lost revenue comes to roughly €366 billion a year, more than twice the entire annual Horizon Europe research budget the European Parliament is currently haggling over.

Compound Consequences

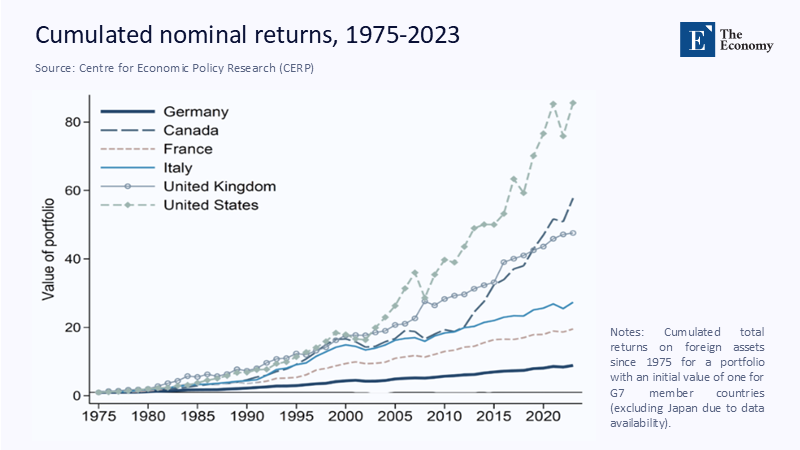

The immediate income hit is only the first-order cost; the more punishing damage runs through compounding, as Figure 2 shows.

Had a German pension fund placed a single unit of capital in a diversified portfolio of foreign assets in 1975 and rolled returns forward, it would today sit on little more than one-seventh of the nominal wealth that an identically timed U.S. allocation produced and barely half the pile amassed by a Canadian dollar. Each incremental percentage point Europe forgoes today attenuates its fiscal space, pension sustainability, and geopolitical leverage tomorrow. If policymakers managed nothing more heroic than lifting the external return to two-thirds of the U.S. level—about 6.0%—the continent would create a new stream of primary income worth €75 billion a year, enough to finance the entire Net-Zero Industry Act subsidy envelope without touching national treasuries. A complete convergence would unlock north of €360 billion, larger than the combined 2025 budgets of research, Erasmus, humanitarian aid, and border management.

The Geography of Caution

Why does European capital yield so little even when it escapes the customs union? Part of the answer is puzzle-free geography. Eurostat's flow tables reveal that almost two-thirds of outward foreign direct investment originating in the EU in 2022 recycled into other EU or EEA destinations, and a further slice disappeared into Dutch and Luxembourg conduits that typically channel funds right back inside the bloc. By contrast, over half of American outward FDI sits in economies whose trend growth outpaces U.S. growth, and two-thirds of Canada's portfolio is parked outside North America. The home bias that once looked prudent when exchange-rate risk dominated corporate treasuries now functions like a quasi-index-hugging strategy at the continental level: safe, familiar, and structurally low-yield.

The Macro Handbrake

Even before firm-level choices enter the frame, the macro backdrop does Europe no favors. Between 2005 and 2023, real GDP in the euro area expanded by 21%, and the United States grew by more than a third. The demographic arithmetic is grimmer still. Eurostat projects that the working-age share of the population will fall from 63.9% in 2022 to 60.0% by 2038 and slide toward 54.4% by the end of the century, implying the loss of 57 million prime-age Europeans. Slower labor-force growth drags on domestic demand, depresses corporate earnings, and, via the discount-rate shortcut embedded in most hurdle-rate spreadsheets, shaves points off the valuation of future cash flows the moment a project proposal reaches the finance committee.

Risk Culture and the Frontier Premium

North American investors, partly because they began globalizing earlier and partly because public-market norms acculturated them to draw risk, accept volatility as the entry fee for outperformance. Canadian pension funds wrote that lesson into their mandates three decades ago when Ottawa's "30% rule" freed them to allocate nearly a third of assets beyond domestic borders; today, Ontario Teachers' and CPP Investments routinely book double-digit long-run internal rates of return on toll roads in Santiago or solar farms in Gujarat and regard annual mark-to-market swings of 10% as background noise. In continental Europe, by contrast, the last generation of CFOs has been taught—in polite prose by Basel supervisors and in harsher language by the euro-crisis horror film—that stability and solvency are synonymous. A survey this spring of risk committees at forty German and French industrial multinationals found ex-ante equity hurdle rates for green-field projects in sub-Saharan Africa that were fully 220 basis points below comparable Canadian targets; when a corporation prices risk cheaply, it will logically choose fewer risky projects. This highlights the urgent need for a shift in risk culture in Europe.

Regulation: The Invisible Handcuffs

The policy operating system bakes that conservatism into law. Under Solvency II's standard model, a euro of equity risk in a frontier economy attracts a capital charge of 49% versus 39% for a developed-market counterpart, a ten-point penalty that, in effect, taxes diversification. European banking regulation piles on more weight: where the U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation socializes tail risk and allows American banks to extend balance sheets across borders, the EU still lacks a shared deposit insurance scheme. The logical result is that loan officers restrict the outward tilt of their books because the local sovereign shoulders the full contingent liability. Prudence, in other words, becomes a structural yield haircut. However, the potential benefits of regulatory changes could significantly enhance Europe's foreign investment returns.

The Feedback Loop and the Flow Bust

Numbers from EY's 2025 Attractiveness Survey and corroborating data from Reuters show how the behavioral and regulatory circuits lock into a vicious loop: announced FDI projects in Europe fell 5% in 2024 to a nine-year low, with Germany's tally down 17%, and France's down eleven. The continent is shrinking both as a destination and a source of risk capital. Eurostat confirms the double bind—Europe's inward flows were negative €101 billion in 2022, while outward flows registered only €213 billion, well below pre-pandemic norms. Less capital arriving means fewer foreign-managed projects from which local executives can learn to price uncertainty; less know-how at home, in turn, dissuades domestic capital from venturing abroad, sealing the loop.

Monetary and Strategic Stakes

The stakes extend far beyond corporate income statements. Europe's structural current account cushion has long relied on primary-income surpluses generated by its foreign asset book. Suppose the book underperforms even marginally while the United States repatriates almost $300 billion of affiliate profits in a year. US inward investors earn barely five-and-three-quarter percent on their stakes. In that case, the euro area's net international investment position converges toward the wrong side of zero. A continent that misses earnings at home and abroad will finance its welfare state sooner or later through debt or devaluation; the first road leads to fiscal ceilings and inflation politics.

Re-wiring the Risk Circuit

Fixing the yield gap does not demand federal fiscal transfers or a Treaty convention; it requires a more surgical adjustment of incentives. A first step would be to split emerging-market equity into a discrete Solvency II bucket priced off empirically observed volatility rather than the blanket equity‐risk shock applied today; even a five-point reduction in the capital charge would liberate tens of billions on insurer balance sheets now warehoused in negative-yielding government debt. Parallel tweaks to the Capital Requirements Regulation could allow systemically essential banks to net a portion of sovereign risk across the union, shrinking the penalty on cross-border maturity transformation and freeing up headroom for extra-European project finance. The European Investment Bank, for its part, could redirect a slice of its External Lending Mandate to first-loss tranches in frontier-market infrastructure that meets strategic autonomy goals—battery minerals in Namibia, grid storage in Indonesia, health logistics in West Africa—leveraging private balance sheets with public catalytic capital. Pension trustees then become the decisive swing vote. If the Occupational Pensions Directive raised the ceiling on unlisted equity from its de facto low-single-digit level to 15% over a decade, Europe's $5 trillion pension universe would seed a pool of patient capital larger than the EIB itself, capable of chasing the frontier premium the way Canadian plans have for a generation.

A Future Worth Compounding

The so-called "foreign returns puzzle" dissolves on inspection. Europe is not condemned to lower returns by geography or industrial structure; it chooses them through a matrix of rules and habits that valorize stability over the upside. The choice has never been starker. Either the continent continues to circle capital inside a demographically shrinking market and settles for five cents on the euro, or it consciously stretches its risk parameters and commands nine. The bridge depicted in the article's header image—a golden arch of coins rising from Frankfurt's Main to Toronto's Harbour—was meant as a metaphor. Still, like all metaphors, it is also an invitation. Build the bridge in regulatory code and boardroom culture; compound interest will do the heavy lifting. Decline the invitation, and Europe can look forward to every future edition of the FDI tables telling the same story in darker ink: capital flows where it is welcomed, and yield flows with it. The arithmetic is brutal but remains reversible while time and demographics permit.

The original article was authored by Franziska Maruhn, a Lead Economist at the European Central Bank, along with four co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "The foreign returns of nations: A puzzle," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.