Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The actual cost of aging in America is not just a future nursing-home bill or next year’s Medicaid appropriation. It's the actuarial gamble every household is forced to make today. This stark reality underpins the following argument: federal policy was designed with half-hearted measures, the private market soon realized the numbers didn't add up, and families have been left to bear the burden. What may seem like a mix of ideology, commercial retreat, and federalism is, in fact, the inevitable result of rejecting universal risk-pooling as the baby-boom cohort approaches frailty. The need for a universal system becomes increasingly apparent.

Partnership Laws: A Nudge Too Small to Matter

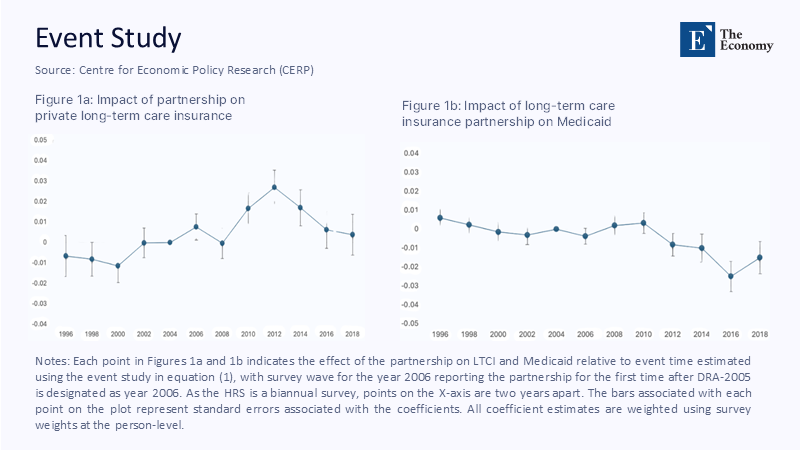

Congress has spent a quarter-century coaxing households into buying stand-alone long-term-care insurance (LTCI). Tax deductions in the 1996 HIPAA, asset-protection incentives in state “Partnership” laws, and premium-payment flexibility under the 2005 Deficit Reduction Act were all advertised as catalytic. In practice, they shifted behaviour by mere decimal points. The best evidence comes from an event study built on the Health and Retirement Study: four years after a state adopted a Partnership programme, private coverage rose by scarcely one percentage point before fading back toward zero (see the dark-blue trajectory in Figure 1a). On the other side of the ledger, Medicaid utilisation hardly budged and, if anything, drifted upward a decade later (Figure 1b). A rational middle-class household interpreted those plots as confirmation that the public safety net would still be there if private premiums proved unaffordable, precisely what happened.

Federal design, in short, outsourced the heavy lifting to insurers while allowing ideological opponents to claim victory over “big government.” The result was a policy so gentle that it never changed expectations, let alone actuarial tables.

Why Insurers Walked Away

Commercial underwriters initially welcomed the invitation—until experience data arrived. Longevity kept beating projections, lapse rates came in far below model assumptions, and the cost of formal care inflated faster than medical CPI. A detailed look at Genworth policies tells the story: products priced in the late-1990s assumed 3–4% annual lapse; actual lapses ran below 1%. Every extra cohort holding on to coverage pushed future claims up while the premium base was fixed. State regulators permitted 40–90% catch-up premium hikes when the books tipped. Middle-aged couples facing quadrupled invoices voted with their feet, and the supply side shrivelled from more than a hundred carriers to barely a dozen today.

The implosion was foreseeable. LTCI is a thirty-year commitment against an expenditure with wide variance. Without a universal mandate, the risk pool skews toward buyers who expect to claim, and the product is either underpriced or unaffordable. The United States tried to square that actuarial circle by assuming “the market” would innovate. Instead, insurers discovered the only profitable innovation was exit.

Medicaid’s Shadow Entitlement

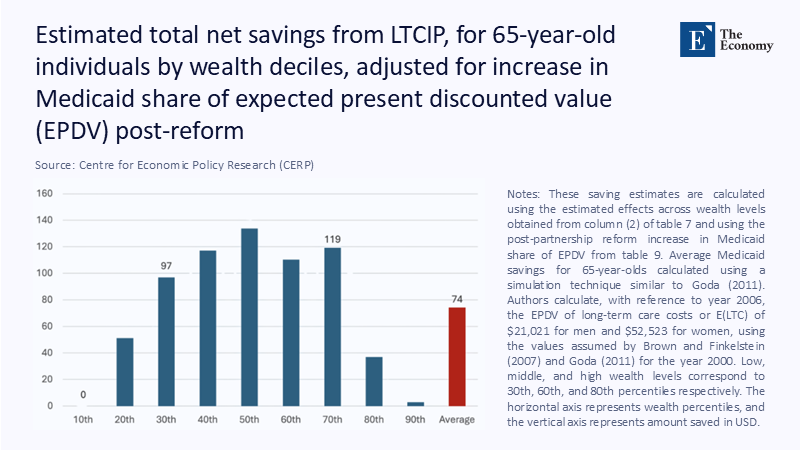

Because the private sector contracted, Medicaid now finances over half of all U.S. long-term-services-and-supports (LTSS) spending—more than $240 billion last year. Yet the benefit remains means-tested: households must “spend down” until countable assets fall below roughly $2,000 (rules vary by state). Partnership policies were supposed to let buyers shield assets dollar-for-dollar up to the face value of their contract, trimming Medicaid rolls. Figure 2 quantifies the disappointment. Simulations of expected lifetime savings show that only households in the middle-wealth quintiles reduce Medicaid claims by meaningful amounts—roughly $100,000 each—while the poorest decile saves nothing (they were eligible anyway). The top decile hardly changes behaviour because they can self-fund care.

Even that narrow middle-class victory is temporary. Once Partnership buyers exhaust the sheltered slice of assets, they enter Medicaid just as any other applicant would, meaning the public purse remains on the hook for tail-risk years.

The Hidden Care Economy

Official ledgers understate the magnitude of the policy failure because they omit the unpaid workforce that steps in when cash insurance is missing. AARP pegs the imputed value of family caregiving at roughly $600 billion, larger than the federal education budget. Daughters and daughters-in-law shoulder most of those hours, trading career progression and retirement security for caregiving duty. Every percentage-point shortfall in formal insurance translates into uncounted labour that magnifies gender inequality.

What Happened Abroad—and Why It Matters

Sceptics often point out that European or East-Asian demographics differ from America’s, yet the international record is instructive. The Netherlands devotes 4.4% of GDP to a universal LTC system; Norway and Sweden exceed 3%. South Korea, hardly a bastion of welfare largesse, launched contribution-financed long-term-care insurance in 2008 and, within a decade, doubled facility capacity while covering nearly 10% of seniors. Seoul’s scheme is not costless—premiums have already risen—but it avoids the destitution-or-Medicaid binary that defines U.S. ageing. The common denominator abroad is compulsory participation: universal premiums eliminate adverse selection and make the benefit politically unassailable.

A Plausible Hybrid for the United States

Suppose America copied the payroll-tax architecture of Medicare Part A, adding a one-percent contribution split between employer and employee, on today’s wage base that yields roughly $120 billion annually—enough to fund a basic lifetime LTC benefit of about $75,000, indexed to CPI-medical. Vesting after ten years of contributions, à la Washington State’s WA Cares Fund, would discourage strategic timing. Benefits should be cash-convertible and partially assignable to family caregivers, formally recognising the economic value of unpaid labour while avoiding the perverse incentive to institutionalise. Private insurers, relieved of catastrophic liability, could re-enter as sellers of top-up riders—an echo of Swiss or Dutch models where public coverage and private options coexist without cannibalising each other.

The key political move is to admit that public dollars already pay: they arrive late, after families have been stretched and assets depleted. A universal premium would be an upfront, actuarially transparent swap for a hidden, back-end liability that crowds out other state priorities.

Why Delay Is the Costliest Choice

By 2030, every baby-boomer will be at least sixty-five, adding more than seventy-three million seniors to the risk pool. If the historical nine-percent nursing-home inflation rate merely halves, nominal costs will still double in a decade. States, obliged to balance budgets annually, will find Medicaid squeezing everything from K-12 funding to infrastructure. Therefore, waiting is not neutral; it is an affirmative decision to let the demographic wave roll over public finance and family wealth. The cost of delay is financial, social, and human.

Redrawing the Social Contract

Long-term care is where longevity collides with libertarian instinct. The United States thought it could resolve the conflict with nudges and voluntary insurance. Still, the data—including the muted Partnership bump in Figure 1a, the negligible Medicaid relief in Figure 1b, and the uneven fiscal gains in Figure 2—tell a different story. Private carriers are rationally unwilling to sell what policymakers are reluctant to mandate. Families are rationally unwilling to pre-pay for coverage that may be repriced or rescinded. And governments are irrationally committed to picking up the tab anyway, only later and at higher cost.

A federal hybrid—universal base coverage, plus optional private riders, would transform that dynamic by aligning incentives across households, insurers, and taxpayers. It is not radical; it is actuarial. Until lawmakers accept that mathematics, America’s long-term-care “strategy” will remain what it has been for three decades: hope children can afford compassion and time, and pray that the next recession does not make those calculations impossible.

The original article was authored by Joan Costa-i-Font and Nilesh Raut. The English version of the article, titled "Expanding private insurance for long-term care to reduce public spending," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.