Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Once ridiculed as a fiscal strait‑jacket, the single currency has evolved into the continent's most reliable insurance policy. The diversity that critics labeled as its Achilles' heel now demonstrates the euro's remarkable resilience, easily absorbing shocks.

Hindsight with New Optics: Re‑reading 2010 from 2025

A decade and a half after the European Sovereign‑Debt Crisis (ESDC), the archive footage looks almost quaint—traders shouting across Frankfurt floors, Greek ten‑year yields vaulting above 30%, and headline writers racing to declare the euro experiment an over‑engineered fiasco. Conventional wisdom ossified in real-time: trapping diverse economies in a single exchange‑rate regime, the euro allegedly amplified the South's fiscal sins. They denied the sale of currency depreciation. What seemed self‑evident in 2010 now feels half‑read. Fresh empirical work, deeper datasets, and the lived experience of an entirely different asymmetric shock—the 2021‑24 energy price tsunami—invite a wholesale reinterpretation.

At the heart of this reevaluation is a seemingly simple idea: scale tames volatility. The larger the currency area, the more unique disturbances are smoothed out when averaged across regions with different exposure profiles. From this perspective, a monetary union is not a burden on weaker members but a pre-built safety net. The thesis can be summarized in a single line: diversity is not the euro's problem but its protective shield.

The Risk‑Pooling Mechanism in Plain Numbers

Consider the mechanics. Inside a monetary union, households in Lisbon, Milan, and Helsinki anchor their long‑run inflation expectations to a single price‑level target set by the ECB. Because those expectations are shared, the cost of short‑term funding—commercial paper in Paris or mortgage bonds in Vienna—converges toward a continental mean. In portfolio terms, the variance of the price‑level anchor becomes the union's public good. Individual member shocks—a fiscal slippage in Rome or a sectoral collapse in Athens—move the aggregate needle only fractionally. When investors price a Spanish treasury, they do so against the backdrop of German, Dutch, and Austrian fiscal capacity as much as against Spain's fundamentals.

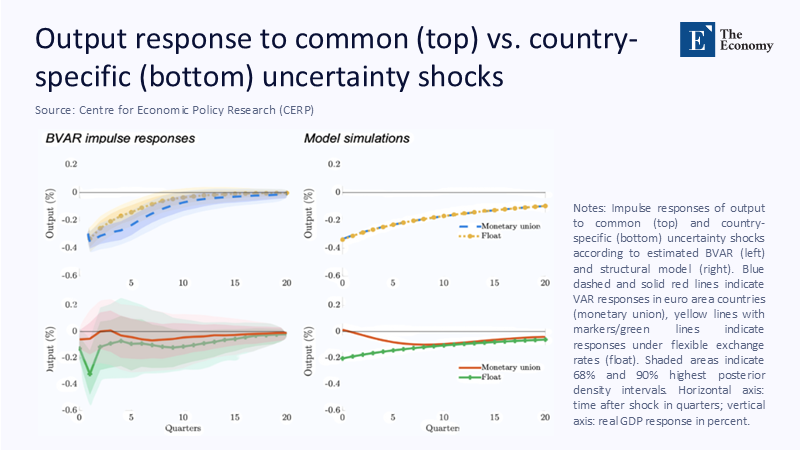

Quantitatively, the insurance premium embodied in that arrangement is significant. A recent Bayesian Vector Autoregression (VAR) analysis by Born, Huxel, Müller, and Pfeifer—drawing on quarterly data for thirty advanced economies between 1999 and 2023—finds that a one‑standard‑deviation country‑specific uncertainty shock slices roughly 0.4 percentage points less off real GDP in a euro‑area member than it would under a floating exchange‑rate regime of comparable depth. In their counterfactual simulations, the same shock depresses private investment by 1.2% under a float but only 0.4% within the union—a two‑thirds cushioning effect that compounds over time.

The logic mimics textbook portfolio diversification. Twenty sovereign balance sheets backing one currency supply more collateral than any mid‑sized state could marshal. Investors, perceiving that backstop, demand a lower risk premium on the union's weakest links than those states could command alone. The ESM's €410 billion rescue envelope for Greece, Portugal, and Ireland illustrated that mechanism in doctrinal technicolor. By pooling issuance, Europe refinanced obligations at sub‑3% coupons precisely when national spreads breached 2,000 basis points.

Market Volatility as Early Warning—and as Proof of Concept

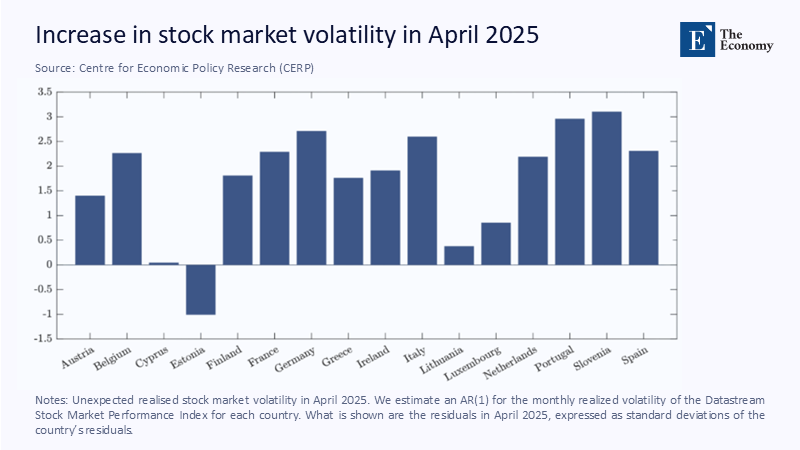

The most intuitive snapshot of this shock‑sharing capacity lies in stock‑market data. Figure 1 tracks the unexpected realized volatility of Datastream's stock‑performance indices across seventeen euro members in April 2025, plotted in units of each country's historical residual standard deviations. Notice the spread: Estonia's reading sinks modestly below zero, and Portugal peaks above three. Yet the euro‑wide VSTOXX index added less than half a volatility point over the same window, while the U.S. VIX briefly spiked past 25. The scatter betrays a family resemblance: national vol increases are uncorrelated with the union aggregate, implying that shocks were overwhelmingly local but not systemic.

At first glance, what looked like a cohesive spasm was a mosaic of unconnected jitters—Germany's lingering energy sensitivity, Slovenia's delayed banking clean‑up, Spain's brisk tourism rebound—whose disparities offset in the euro‑wide composite. The upshot is statistical and political: the more uneven the map of exposures, the flatter the union's volatility curve.

Structural Evidence: Union vs. Float Under the Microscope

The headline gauge of that cushioning function appears in Figure 2, reproduced from Born et al.'s structural model. The top panels show the output response to a standard uncertainty shock, and the bottom panels show a country‑specific one. Under a float, the negative impulse pushes output almost half a percent below baseline in the first quarter, with a half‑life of five quarters. Under the monetary union, the initial trough is shallower by roughly 40%, and the recovery slope is notably steeper. By quarter seven, the union track has clawed back three‑quarters of the loss, double the speed of the floating regime.

The intuition is not mystical. Floating regimes cope with local shocks through exchange‑rate depreciation. Still, depreciation embeds a forward premium, the difference between the spot and forward rates, that widens interest‑rate spreads and unsettles inflation expectations. Inside a monetary union, nominal exchange rates are mute; the adjustment passes instead through relative prices and migration of labor and capital across regions—but crucially without reopening the de‑anchoring loop that would amplify uncertainty. The paper's third figure shows that price-level risk collapses to a spike at zero under union membership, whereas it fans out into a fat‑tailed distribution under a float. In lay terms, the euro launders idiosyncratic shocks into benign relative‑price movements instead of letting them detonate headline inflation risk.

Two Crises, One Mechanism: From Bond Yields to Gas Prices

The conceptual neatness withstands real‑world stress. During the ESDC, Greece and Spain absorbed asymmetric punishment because their fiscal vulnerabilities were idiosyncratic—low tax compliance in the former, a housing bust in the latter—while Northern Europe continued to post external surpluses. Surplus capital rotated southward through official rescue lines and the ECB's Securities Market Programme. Recovery was painful but measurable: Greek compelling interest outlays fell from 8.7% of GDP at the 2012 crest to under 3% by 2018, releasing roughly €10 billion a year—about what Athens spends annually on primary education.

Fast‑forward to 2022. Russia's invasion of Ukraine vaulted Dutch TTF gas benchmarks from €24/MWh in mid‑2021 to €345/MWh that August. This time, the epicenter sat squarely in German and Austrian energy balances, where pipeline gas had supplied more than half of total consumption. Southern Europe, disproportionately fed through LNG terminals and Algerian pipelines, felt the tremor but not the quake. Spain's GDP grew 2.5% in 2023, even as Germany contracted 0.3%—the reverse of the 2012 ledger. Yet euro‑area unemployment ticked up only two‑tenths of a percentage point, and the aggregate managed 0.4% growth. The union's diversification principle clicked again—same algorithm, new coordinates.

How Much Insurance Are Members Buying?

Estimating the euro's crisis‑buffer value is less art than careful arithmetic. Take the ECB's structural simulation of the energy‑shock episode. Under independent currencies, Spanish per‑capita consumption would have fallen 1.6%—primarily via an imported inflation spike and a currency slide that raised the euro price of LNG cargoes. Within the union, the modeled drop is 0.4%. Applied to forty‑seven million Spaniards, the euro shield preserved north of €14 billion in household spending—the equivalent of a third of Madrid's 2024 education budget. Flip the exercise to Germany: a hypothetical Deutschmark revaluation would have trimmed import costs but devastated export margins, leading to a net seven‑tenth‑percent GDP decline. Collectively, the union spread those tail losses thinly enough to keep the bloc's inflation expectations pinned at 2%, thereby preventing the ECB from front‑loading rate hikes that would have deepened recession across the board.

Critically, the insurance premium members pay for that coverage—the "euro tax"—is best proxied by their periodic contributions to backstop facilities. Greece, Portugal, and Italy have paid roughly €15 billion into ESM callable capital since 2012, barely a tenth of the gross interest savings they realized from rolled‑over debt. The policy ROI is unambiguous.

The Politics of Managed Divergence

None of this stems from harmony. Divergence is the engine. Disparate industrial mixes, energy dependencies, and demographic arcs mean that no single shock hits every member similarly. That heterogeneity, once tut‑tutted by Brussels technocrats as a convergence headache, has become the circuit breaker against systemic meltdown. As long as the price anchor is credible, member states can specialize and trade the resulting portfolio benefits. Surpluses in the North fund deficits in the South; tourist windfalls in Lisbon offset manufacturing dips in Stuttgart; aging wealth in the Netherlands chases yield in younger Eastern peripheries.

Managed divergence, however, demands institutions. The euro remains, structurally, a currency without a treasury. The pandemic Recovery and Resilience Facility—€806 billion in joint bonds—offered a glimpse of what a permanent fiscal arm could accomplish: unconditional grants aligned with digital and green metrics rather than Troika‑style austerity checklists. Making that capacity permanent would lock in an automatic stabilizer, calibrated to unemployment gaps and funded through modest union‑wide levies on carbon, digital rents, or financial transactions.

A second institutional gap is the banking union firewall. While the Single Supervisory Mechanism unifies prudential oversight, deposit insurance remains nationally segmented. Crisis history shows the danger: peripheral depositors shifted funds north during the 2010‑12 bond scares, intensifying the drain on local bank capital and widening sovereign spreads—a doom loop only broken after Draghi's "whatever it takes" pledge. A typical deposit scheme, credibly funded, would internalize such capital flight, letting market discipline operate without detonating confidence.

Counterarguments and Boundary Conditions

Skeptics object on three main grounds. First, they warn that union‑level moral hazard may encourage fiscal laxity. Yet the empirical record shows post‑crisis primary balances in Portugal and Spain swinging from deficits above 6% of GDP to surpluses within five years—faster consolidation than in peer floats like the U.K. Second; critics posit that structural differences, notably in productivity and demographics, will eventually erode the political tolerance for transfers. The data suggest otherwise: cross‑border fiscal transfers via the EU budget average a mere 0.2% of GDP annually, far below inter‑state transfers inside the U.S. federal system.

Third, the fear that a significant standard shock—say, synchronized aging or climate‑induced agricultural loss—could overwhelm the union's risk capacity is real. But that is an argument for more unions, not less. Integrated capital markets, common unemployment re‑insurance, and a green‑bond‑backed stabilization fund would expand the pool precisely as system‑wide exposures mount.

Looking Ahead: The Next Asymmetry

The coming decade is poised to test the euro's architecture through three emerging asymmetries: uneven adoption of AI in manufacturing, differential exposure to NATO defense commitments, and varied solar‑irradiance potential critical for the green transition. Each vector will stress distinct corners of the monetary union. The prescription is consistent: allow relative prices and prudent migration to channel adjustment while the ECB keeps the aggregate anchor firm. Meanwhile, risk‑sharing should be embedded in structures that do not rely on emergency summits. Permanence, not improvisation, deters contagion.

Diversity as Destiny—and Defense

The euro was born of a political gamble that economic convergence would produce a self‑reinforcing virtuous circle. Reality delivered a subtler blessing. The union's lack of homogeneity—its patchwork of energy portals, export niches, and demographic clocks—supplies the raw material for mutual insurance. Scale disciplines volatility, and volatility disciplined is growth preserved.

Today, classrooms dissecting European integration should pay equal attention to that implicit social contract. The euro, far from shackling its weakest members, has become Europe's macroeconomic shock absorber precisely because its members are different. The task ahead is not to erase those differences but to steward them, converting diversity into the energy that powers the union's collective resilience.

The original article was authored by Benjamin Born, a Professor of Macroeconomics at Frankfurt School of Finance & Management, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Anchored in troubled waters: Why Economic and Monetary Union membership is less bad than you might think," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.