Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Every abandoned vacancy is a silent vote against the economic geography that Westminster imagined when it pulled Britain out of the single market. This single observation underpins the following argument: by closing the door on the factor it lacks most—mid-skill labor—the United Kingdom has set in motion a slow, relentless restructuring that standard trade theory predicted with eerie precision. Now stretching into 2025, the evidence shows two diverging corporate survival paths, an outward-shifting Beveridge curve, and a sectoral map scarred by shortages. What looks like a medley of anecdotes—care homes capping admissions, fintech teams sprouting in Vilnius, orchards left unpicked—is the inevitable anatomy of the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem-made policy.

The Heckscher-Ohlin Lens, Updated for 2025

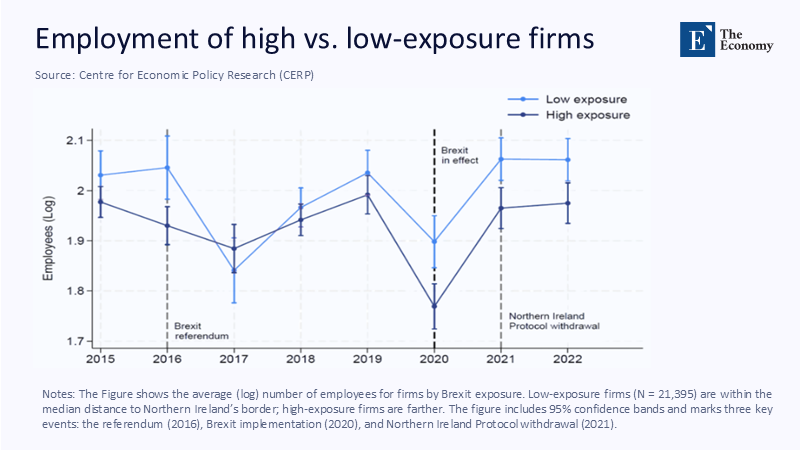

When countries restrict imports of a scarce factor, the canonical Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) model predicts that production will tilt toward activities using the abundant factor—in Britain's case, capital—and contract along labor-intensive margins. Newly released micro-data from the CEPR study of more than 21,000 firms arrayed along the Irish border confirm that prediction with stark clarity. Companies situated farthest from Newry—the last friction-light gateway to EU labor—shed up to 15.7% of their workforce after 2020 once controls for Covid, exchange-rate movements, and sector mix are stripped out. By contrast, low-exposure firms, clustered within commuting distance of cross-border labor flows, registered only modest attrition.

The temporal markers in Figure 1 matter. The downshift began not at the 2016 referendum but at complete legal withdrawal in 2020 when visas replaced free movement. The H-O mechanism is, therefore, not a psychological panic—investment cuts would have preceded the legal cut-off, but a textbook change in relative factor prices: the marginal hour of EU labor became dearer overnight, so labor-intensive production shrank.

Twin Corporate Survival Paths

Aggregate theory conceals firms' micro-choices when confronted with a spike in labor costs. The CEPR panel divides neatly into two trajectories. First is the "shrink-in-place" path: SMEs bound to local demand—regional builders, hairdressers, elder-care homes—accept higher wage bills or scale back hours. A Gloucestershire lettuce grower quoted in parliamentary evidence last autumn crystallized the dynamic: "We left eighty acres unpicked because there were not enough pickers at £12.50 an hour." Such stories dominate the domestic press and nurture the crisis narrative, yet they describe only half the picture.

The second path is "hire elsewhere." Multinationals and tradable-service firms re-planted roles inside their continental subsidiaries. London-headquartered ad agencies shifted production teams to Lisbon; fintechs booked software engineers in Vilnius; university spin-outs registered entire research entities in Eindhoven. These firms still serve British customers, so headline GDP masks the migration, but payrolls drift abroad while domestic job ads evaporate. The CEPR data show that firms with pre-existing foreign sales channels suffered one-third less of the head-count shock than locally anchored peers, confirming that global networks cushion the blow and provide a sense of resilience in the face of Brexit.

Vacancy Dynamics and the Distorted Beveridge Curve

If the labor market were adjusting smoothly, vacancy numbers would fall one-for-one with the supply of workers. Instead, the UK's vacancy–to–unemployment (V/U) ratio has behaved perversely. Official data put vacancies at 761,000 for February-to-April 2025, down 538,000 from their 2022 peak. Yet, the number of job-seekers per posting remains historically thin, with 2.1 unemployed persons per vacancy—the highest ratio since 2016.

Economists read that outward shift in the Beveridge curve as a collapse in matching efficiency: even when vacancies tumble, the pool of available, appropriately qualified labor shrinks faster. Casey and Mayhew's Beveridge-curve study estimates that mid-2022 the V/U ratio was 25% higher than it would have been without Brexit's restrictions. As labor economists note an outward-shifted curve is not a business-cycle kink but a structural one.

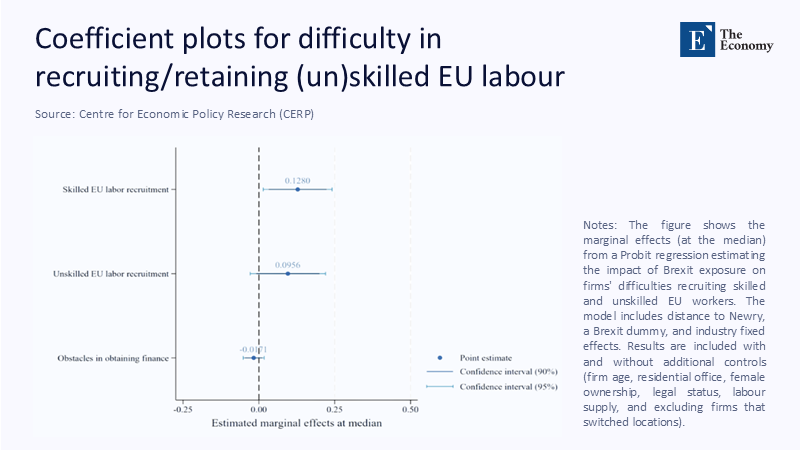

Figure 2 translates the Beveridge narrative into corporate testimony. The Probit coefficients, centered at 0.128 for skilled and 0.096 for unskilled EU labor, reveal that highly exposed firms are more likely to report recruitment bottlenecks. At the same time, their probability of citing finance as a constraint is statistically indistinguishable from zero. In other words, money is plentiful; human resources is not.

Sectoral Portraits: Agriculture, Construction, and Tech Divergence

Disaggregated vacancy data sharpen the picture. Construction vacancies have fallen 26.7% in the quarter, the steepest drop of any industry, precisely because the sector once drew heavily on EU-8 carpenters and electricians who can no longer enter on short notice. Agricultural vacancies show similar contraction, but output declines rather than capital substitution dominate: farms leave orchards unharvested instead of installing robots priced for Californian mega-groves.

Technology tells the opposite story. Vacancies in information services dipped only marginally. Firms deployed remote-first contracts, effectively importing labor digitally. A Manchester videogame studio now lists job ads stipulating "UK or EEA-based, remote." These jobs appear in UK GDP when royalties roll in, but the pay slips are issued in Warsaw and Porto.

That divergence is the H-O model made visible: sectors that can blend capital and code displace the mobility barrier, while place-bound services cannot. The distributional impact is regressive, hollowing out wages in rural and lower-productivity regions even as high-tech clusters ride out the storm. This regressive impact on wage distribution underscores the urgency of addressing the issue and finding solutions to mitigate the effects of Brexit.

Migration Flows and Labour Composition Shifts

Headline migration numbers reveal a parallel realignment. Provisional ONS estimates show total net migration falling almost 50% to 431,000 in the year to December 2024, following a post-Brexit crackdown on work and study visas. Within that aggregate, the EU component has flipped negative: fewer EU citizens arrive than depart, reversing two decades of net inflows.

Payroll data illuminate who left. Between June 2019 and June 2021, pay-rolled employment held by EU nationals collapsed by 6%, a loss of 171,000 positions, while non-EU employment climbed by 9%. The quality skew is equally stark: sectors with tighter salary thresholds, notably care and hospitality, experienced the heaviest EU exits, whereas health and social work compensated partly via non-EU visas, rising 19 % over the same period.

The composition thus changes twice: by nationality and by skill. Britain still attracts postgraduate AI specialists from India, but the flexible, mid-skill segment that kept logistics, construction, and food processing humming has thinned. The result replicates Ohlin's century-old intuition: when the supply of a scarce factor contracts, its price rises, and the output that embodies it shrinks.

Policy Scorecard and Forward-Looking Options

Five years in, the data allow a sober audit of mitigation efforts. The post-2021 points-based visa scheme, pitched as flexible, has delivered for capital-complementary roles but left manual sectors stranded. Salary thresholds of £38,700 exclude the majority of construction apprenticeships and virtually all farm-hand jobs. The government's one-year seasonal worker program mitigates harvest risk but does nothing for year-round dairy or meat-processing plants.

Domestic training alone will not quickly fill the gap. Apprenticeship starts in construction fell 12% in 2024 despite record vacancy rates. The reason, employers say, is not funding but throughput time: a brick-layer apprenticeship is three years; a Bulgarian worker used to land in Luton on Sunday and lay bricks by Wednesday.

Re-opening labor channels where automation is infeasible ranks first on any output-maximizing policy sheet. A targeted visa for social care aides, capping wages at the 25th percentile, would relieve hospital bed-blocking, which alone costs the NHS upwards of £3 million a week in lost capacity. Sector-specific quotas are politically fraught but economically superior to across-the-board salary floors that entrench regional inequality.

Second, the data argue for refining rather than abandoning mutual recognition of professional qualifications with the EU. Exportable services—architecture, engineering design, legal process outsourcing—pay high wages and substitute easily across jurisdictions. Re-entangling regulation would coax some of those teams back onshore.

Third, economic commentary must retire the fiction that "Brexit hits all firms equally." The lesson of Figures 1 and 2 is granular: exposure, network maturity, and the capital/labor ratio determine resilience. National aggregates disguise a distributional story that is economically regressive and politically explosive.

Mobility as Economic Infrastructure

In 1933, Bertil Ohlin warned that trade barriers ultimately warp domestic factor prices more than they suppress import flows. Ninety-two years later, his theorem is playing out on British soil. The decision to limit labor inflows has not merely trimmed immigration statistics; it has re-drawn the country's productive map, encouraged hidden off-shoring, and clipped the scale of its most labor-intensive services. The vacancy bulletins, Beveridge-curve shifts, and firm-level micro-panels tell one coherent story: the actual cost of Brexit resides less in customs paperwork and more in the retreat of labor demand.

Reversing that retreat demands that policymakers treat human mobility as infrastructure, on par with roads, spectrum, and fiber. Until visas and recognition regimes are rebuilt for sectors that cannot digitize their workforce, the statistic that will most faithfully chronicle Brexit's legacy is the vacancy unfilled, the shift scrapped, and the orchard left to rot.

The original article was authored by Hang Do, a Principal Teaching Fellow in Strategy, Innovation and Entrepreneurship at the University Of Southampton, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "The real effects of Brexit on labour demand," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.