Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

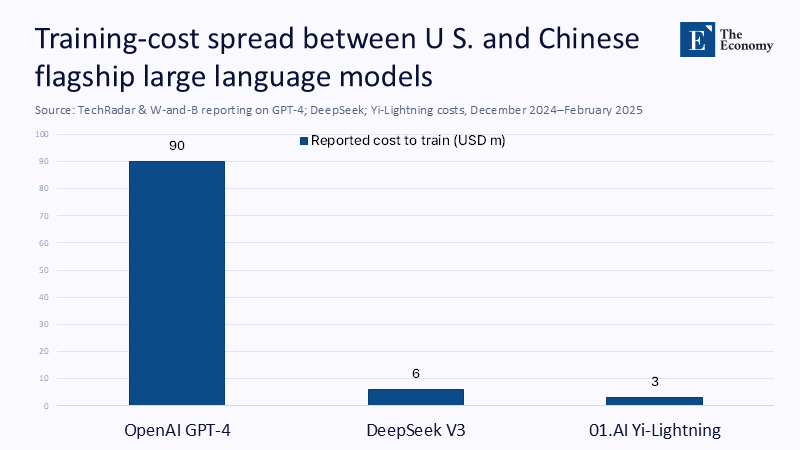

A stubborn fact sets the stage for Australia's AI dilemma: it now costs more to train one US-style frontier model than Canberra spends on its entire "safe and responsible AI" program over five years. That imbalance magnifies every strategic choice Australia makes because whichever side of the U S.–China technological rift it leans toward will effectively subsidize the other half of its AI ambitions. The resulting policy question is not whether Australia can afford to ignore Chinese AI but embrace it without detonating the AUKUS alliance and the wider trust architecture that underwrites Australian security.

Australia at the fulcrum of a bifurcated AI world

Washington and Beijing have spent the past decade stapling AI to their larger geopolitical contests, and the rest of the world now treats advanced models as branded products: "American AI" versus "Chinese AI." The former still wears the halo of technical pre-eminence, but the latter is getting relentlessly cheaper, partly because Chinese firms such as 01.AI and DeepSeek have learned to squeeze more performance from fewer GPUs. The downward price curve interacts viciously with export-control politics: the United States throttles hardware. At the same time, Chinese startups optimize code, leaving mid-sized countries caught between higher costs and diplomatic headwinds.

Australia's long attachment to U.S. strategic guarantees, formalized most recently through AUKUS, makes it unusually cautious. Officials worry that any pivot toward bargain-priced Chinese platforms could be read in Washington as a breach of tech-security solidarity. Yet Canberra's analysts know that staying solely in the U.S. orbit entails a permanent subsidy. Every large-scale model or GPU cluster procured at American prices drains public-sector budgets never designed for computing races measured in billions of dollars.

The economic logic: when training costs outrun national budgets

Australian Treasury allocated A$39.9 million (≈US$26 million) across five years for its flagship AI safety and capability agenda.

OpenAI's single GPT-4 training run absorbed roughly three times that amount in months. DeepSeek or Yi-Lightning-class cycle comes in well below Canberra's whole program envelope. The implication is brutal: if Australia insists on U.S.-grade proprietary stacks, it forfeits budgetary room for domestic data infrastructure, digital-skills visas, and sovereign compute pilots that could widen AI benefits beyond metropolitan research hubs.

Put differently, the choice is no longer between "cheap but risky" Chinese systems and "costly but safe" US ones. It is between importing entire US supply chains or co-engineering cheaper Chinese toolchains that can be subjected to local security audits and democratic oversight. The latter path is politically more challenging but economically rational, and it would give Australia leverage to shape the emerging inspection regimes that even Washington accepts as inevitable for cross-border AI.

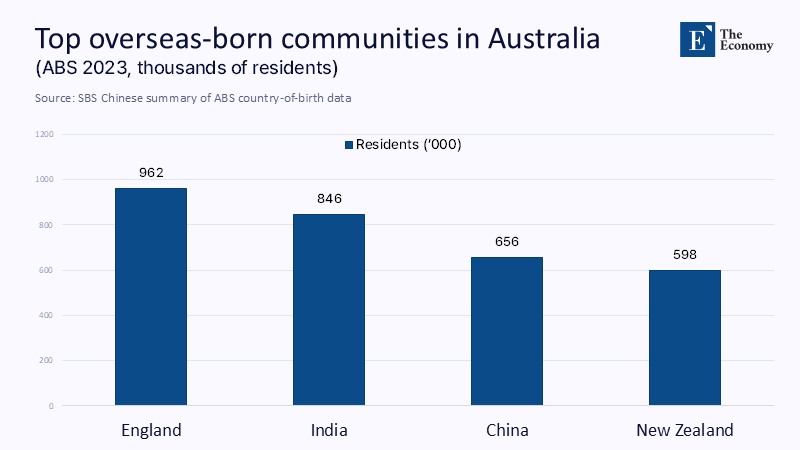

Diaspora leverage: Australia's quiet Chinese talent dividend

If price is one part of the calculus, people are the other. The Australian Bureau of Statistics confirms that 31.5% of residents were born overseas in 2024, the highest share since 1891.

Crucially, 656,000 of those residents are China-born, forming the third-largest migrant cohort after England and India.

That demographic reality supplies Australia with a ready-made bridge into Chinese AI laboratories, academic networks, and bilingual data corpora—assets that smaller Anglophone countries can only rent on the open market. Far from being a diplomatic liability, the diaspora is a policy lever: with the proper guardrails, it can help Canberra access Chinese-language models, red-team them, and fine-tune them for Australian public service and education workloads without surrendering critical IP.

AUKUS anxiety and the diplomatic double bind

None of this plays out in a vacuum. The premise of AUKUS Pillar II—joint advanced-technology development, a key component of the AUKUS agreement—risks being diluted if Canberra courts Chinese model-makers. U S. lawmakers are already bristling at allies installing Huawei 5G gear; Capitol Hill hawks would paint an Australian memorandum of understanding with DeepSeek as "digital Munich." Yet refusing to touch Chinese software creates a dependency on American licensing terms that can tighten without notice, as Europe's startups discovered when API costs spiked in late 2024.

The diplomatic answer is not blanket rejection or uncritical adoption but structured interoperability: Australia can require that any Chinese foundation model run inside "sovereign inference enclaves" hosted on Australian soil, audited by third-party cryptographic attestation, and subjected to export-control-compatible chip partitions. Washington would still grumble, but Canberra could point to stronger safeguards than many U S. cloud offerings.

Ripple effects across the Global South: the Digital Silk Road reboot

The stakes reach beyond Australia. Governments from Jakarta to Nairobi will read that as a de facto green light if a country so tightly woven into U.S. intelligence networks can operationalize Chinese AI. Beijing's Digital Silk Road already supplies undersea cables and smart-city surveillance packages; low-cost generative models would add the cognitive layer that cements technological dependence.

Australian endorsement—explicit or tacit—could propel the next wave of Chinese AI exports, especially to budget-strapped education ministries that need language models in local dialects but cannot pay OpenAI rates. This could significantly shift the balance of power in the AI industry and further strain the already tense U.S.-China relations.

That, in turn, would trigger a fresh round of U.S. sanctions and export-control patches, accelerating the very decoupling Washington hoped to slow. Canberra's strategic misstep could ripple into a new, AI-shaped, non-aligned movement, aligning much of the Global South with Chinese technical standards. At the same time, the West argues over chip license clauses.

Policy prescription: a non-zero-sum playbook

Australia can begin by staging side-by-side trials that pit U.S. and Chinese foundation models against identical education tasks, then publishing the resulting performance, latency, and cost data for parliament. Every foreign model—built in San Francisco or Shenzhen—should be confined to Australian-controlled "sovereign inference enclaves." These are hardware-sealed partitions that keep the weights and telemetry onshore and under equal scrutiny, ensuring that the data and operations of these models are subject to Australian laws and regulations.

The nation's large Chinese-speaking research community can then red-team Mandarin and dialect outputs, turning diaspora expertise into an early-warning system for censorship triggers, hidden biases, and security flaws. Framed to AUKUS partners as a way to reduce single-vendor dependence rather than to court Beijing, this tightly audited pluralism lets Canberra cut costs, harden defenses, and demonstrate to the broader Indo-Pacific that openness, when bounded by rigorous safeguards, offers a more durable path to collective technological resilience than exclusion alone.

Choosing Pragmatic Pluralism

Australia cannot relinquish the price asymmetry that Figure 1 lays bare or the demographic leverage illustrated in Figure 2. It can, however, convert those realities into bargaining power—provided it frames Chinese AI as neither a bogeyman nor a bargain-bin savior but as a market force to be disciplined by Australian norms and technical due diligence.

Such a stance would honor AUKUS commitments by hardening supply-chain safeguards, even as it honors economic reality by admitting cheaper Chinese computing into the marketplace. Just as important, it would offer a roadmap for other middle powers that refuse to choose between ideological loyalty and fiscal sanity. If Canberra walks that tightrope, it may find that the best way to sustain Western technological leadership is not to cordon off Chinese AI but to pull it, visibly and conditionally, into an open rules-based system—one in which price and principle can finally coexist.

The original article was authored by Marina Yue Zhang, an associate Professor at the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney, along with three co-authors. The English version, titled "Australia’s AI ambitions hinge on collaboration with China," was published by East Asia Forum.