Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Every euro a woman in a high-income economy adds to her paycheque is now a euro her country quietly subtracts from its cradle count. The same advances that have lifted female education, wages, and boardroom presence have mechanically inflated the private price of childbirth, turning motherhood into the costliest career move of the 21st century. Unless that opportunity-cost shock is redistributed across employers, the state, and fathers, affluent societies will keep discovering that progress for individual women can—paradoxically—undercut the collective birth rate they need to stay fiscally solvent and socially dynamic.

Success Has Become the Silent Tax on Fertility

Germany's post-industrial miracle—rising female university completion, closing hourly pay gaps, record-high dual-earner couples—has delivered a demographic own-goal. When the Federal Statistical Office updated its tables in April, the headline number was brutal: the fertility rate sank to 1.35 children per woman in 2023, the lowest since reunification. The drop is not a cultural whim; it is a market signal. As women's pre-birth salaries climbed, the long-run child-earnings penalty—the percentage gap between a mother's actual and counterfactual income a decade after first birth—has almost doubled since the mid-1960s.

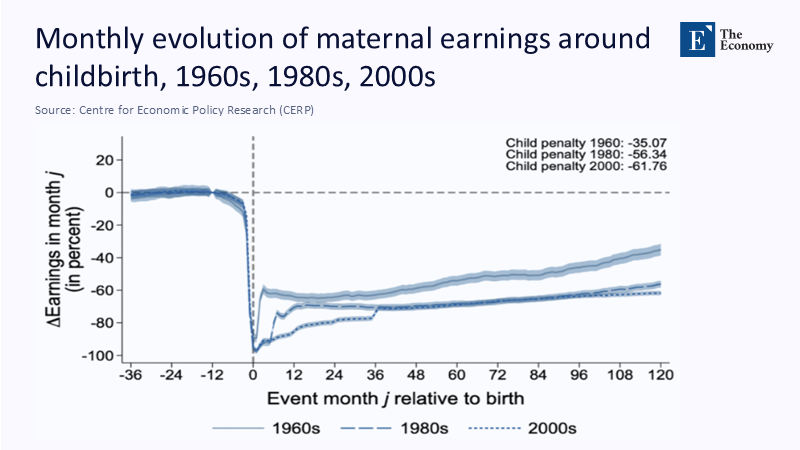

Below, Figure 1 captures that cliff. The solid line shows mothers born in the early 1960s; the dotted line covers women born four decades later. The deeper the cohort's human capital investment, the steeper the income plunge in the exact month of childbirth, and the slower the recovery. Opportunity cost alone does not explain the shape; what matters is that managerial pay escalators, bonus cycles, and promotions operate on strict calendars. Missing a single cycle reverberates through lifetime compounding. In effect, career success has become the silent tax on fertility, levied precisely when biology insists on a decision.

Why Longer—but—Under—Funded Leave Does Not Fix the Valley

Berlin's marquee response is Elterngeld: job-protected leave up to 36 months, with state wage replacement of 65% capped at €1,800 a month. Politics being politics, the ceiling has been frozen in nominal terms since 2007, turning into a 40% real cut. Therefore, a manager netting €6,000 sees replacement fall barely 30%. The new coalition budget even proposes stripping households earning above € 200k from the scheme to save cash.

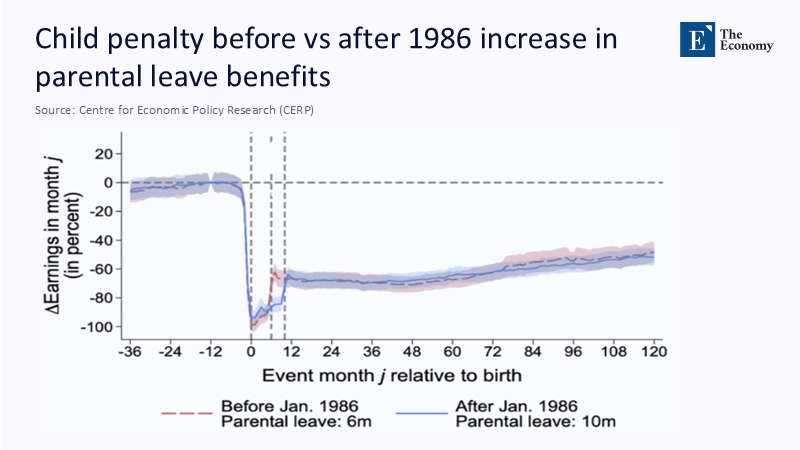

History warns that a duration without adequate pay fails. West Germany lengthened paid leave from six to ten months in 1986; a decade later, the average mother was still 57% below her no-child counterfactual. Figure 2 plots the pre- and post-reform trajectories: the blue line recovers marginally faster in months 6–12 then converges with the red control path. More months at half pay shift costs from the family to the state, but leave the long-range penalty intact.

The First Three Years, Not the First Twelve Months, Are Determinative

Child psychologists were right: ages 0–3 matter most, but labor economists now show they also matter most for maternal earnings. Nearly 70% of the decade-out penalty is accumulated in those 36 months; catch-up after age 3 is glacial. Therefore, a rational policy needs to ensure income over those three years or, better yet, provide predictable childcare to cut the enforced career break in half.

Germany currently fails that test. According to the Paritätischer Gesamtverband, the country is short about 125,000 qualified Kita workers and 430,000 daycare places, an undersupply that forces emergency closures and unpredictable shifts. The Financial Times finds that chronic cancellations push mothers into part-time roles, underutilizing labor and leaving firms scrambling for talent. The Bundesbank has not produced a childcare-specific multiplier. Still, analysts at the IW Institute calculate that overall skill shortages shave up to 0.9 percentage points off annual growth—an estimate implicitly embedding the care gap.

Cross-National Lessons: Why Denmark's Mothers Lose Only 20%

Compare Denmark, where the child penalty hovers near 20%. Copenhagen couples have short, well-paid leave with universal, neighborhood-based, low-fee childcare guaranteed within 500 meters of the home. Slots are a right, not a lottery. Mothers step out for an average of 11 months, fathers for four, and both re-enter their pre-birth salary trajectory. The institutional design shrinks the earnings valley visible in Figure 1 because no one is forced into a multi-year part-time limbo.

Seoul's Billion-Euro Lesson: Cash Cannot Outbid Corporate Culture

Germany's situation pales next to South Korea, whose government has spent over €200 billion on fertility incentives since 2006, yet saw births fall to 0.72 per woman in 2023. Paid leave in Korea is generous on paper—fully paid for the first three months, strongly subsidized for the next nine—but re-entry into chaebol hierarchies is fatal for promotion. Professional women know that one missing appraisal cycle means a stalled career. Result: they marry later, if at all, and often opt out of motherhood entirely. Korea proves that wage subsidies untethered from corporate norms are fiscal sinkholes.

Moving from Universalism to Fair-Risk Sharing: A 60-30-10 Blueprint

Fixing Germany's fertility requires accepting that reproduction is not a private indulgence but a macro-critical infrastructure. The state alone cannot foot the bill, nor should families shoulder the entire risk when the benefits of a new cohort accrue to pensioners, firms, and taxpayers at large.

Under a proposed 60-30-10 covenant:

- The state covers 60% of the first-year wage up to €3 000 net, financed by a marginal surtax on households earning above €250 000.

- Employers bridge 30% for six months, deductible against payroll tax, conditional on guaranteeing the same pay grade, and a four-day phased-return option.

- Family pays 10%, preserving price awareness.

Crucially, the ratios invert for incomes below the median; liquidity, not opportunity cost, is the barrier. At scale, the scheme would cost roughly €3 billion—less than 0.08% of GDP—and substitute unpredictable private loss with predictable, actuarially priced insurance.

Childcare as Physical Capital: A "Stability-Pact Safe" Category

Political attention must now shift from cheques to capacity. Federal grants worth 0.25% of GDP for five years could train 100,000 caregivers and update dilapidated centers. Economists at the Kiel Institute model payback within seven years via higher payroll tax and lower transfer spending. The European Commission already treats green investments as Stability-Pact—"safe"; childcare outlays that lift potential growth deserve identical accounting.

Corporate Norms: Stop the Promotion Clock

Firms have skin in the game. Losing a high-performing engineer forever costs far more than topping up six months of pay. Berlin tech firms now freeze performance-review timelines during leave, treating absence as neutral. Early audits show 92% retention and net savings on recruitment. Multinationals are piloting wage-insurance top-ups capped at € 15k per employee—cheaper than a headhunter's fee. Scaling such practices through collective agreements would turn childbirth from a staffing hazard into a bounded retention investment.

Husband, Company, Culture: Why Leave Must Be Shared, Not Shifted

All evidence indicates that if the entire leave burden lands on mothers, Figure 1's valley widens regardless of duration. The Nordic fix—four non-transferable "daddy months"—spreads career risk and cultural expectations. German uptake is rising but still under 30% of fathers. Employers hold the key: when big firms make at least eight weeks of fathers' leave eligibility a condition for a full bonus payout, uptake soars above 60%. Shared parental leave does not just cut the penalty; it rewires boardroom perceptions that motherhood signals lower commitment.

Will It Work Outside Europe?

Your angle—"I doubt Arab countries would adopt this, but it could work in Germany"—deserves nuance. Gulf states rely on migrant nannies, not public childcare, and female labor-force participation sits below 25%. A German-style wage-insurance model would require reforms in sponsorship laws, pension portability for migrants, and corporate HR practices alien to the region's public-sector-centric labor market. In the medium run, however, even energy exporters confront the arithmetic of aging—and the lesson from Germany, Denmark, and Korea alike is universal: wherever female human capital accumulation accelerates, the private cost of motherhood rises unless society shares it.

Re-pricing Reproduction Before Demography Re-prices Growth

The graphics embedded in this essay tell the story. Figure 1 shows the income crater that opens wider with every cohort of more successful women; Figure 2 proves that more extended but under-funded leave merely shifts that crater two months to the right. Unless childcare becomes as reliable as electricity and earnings risk is pooled across states, firms, and households, every euro of women's wage progress will translate into a higher "baby price tag."

Advanced economies can either pay that price up-front through smart insurance and infrastructure, or pay later via smaller workforces, pension stress, and anemic growth. The maths is merciless, but the policy playbook is clear. With its scientific precision and fiscal caution, Germany can pioneer a new contract that makes success and motherhood complements rather than substitutes. If it fails, the silent tax on fertility will keep compounding—one deferred birth, one empty kindergarten chair, and one lost GDP point at a time.

The original article was authored by Ulrich Glogowsky, a Professor of Economics at Johannes Kepler University Linz, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "The rising cost of motherhood in Germany," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.