Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

There is no such thing as a partial guarantee in global finance: the instant capital takes fright, investors price a sovereign’s promise at par or zero, and the difference shows up as a three-hundred-basis-point jump in corporate loan coupons before the central bank can schedule its next press briefing. That snap judgment—visible in Chile’s Covid-era spreads but fatal in Argentina’s 2001 collapse—reveals the core truth this column defends: government credit backstops shield firms from a sudden-stop shock only when the state’s balance sheet is undeniably sound. Solvency, not rhetoric, is the ultimate policy instrument, and every basis point of perceived fiscal weakness turns a well-intentioned guarantee into an accelerant of the crisis it aims to avert.

When Capital Votes with Its Feet

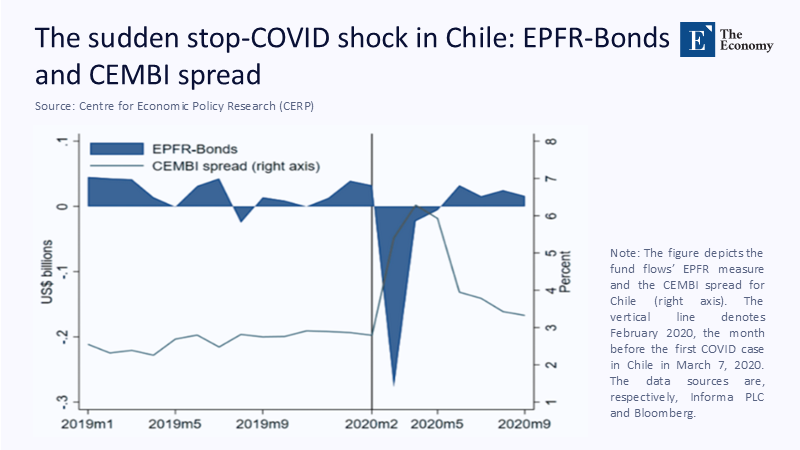

Credibility carries a price tag that only solvent treasuries can pay, and Figure 1 shows the invoice arriving in real time: as soon as Covid-19 reached Chile, bond-fund inflows swung negative by roughly 0.3 % of GDP, and the CEMBI spread on corporate debt exploded from 3% to 7%. That four-point detonation is not an abstract risk metric—it is the difference between a working-capital line rolling at single digits and the same firm staring at a doubled interest bill overnight. In the Heckscher–Ohlin logic, capital scarcity always sends the rental rate sky-high; the chart makes plain that the sovereign’s credit premium determines just how high and fast.

A Heckscher–Ohlin shock in the age of instantaneous capital mobility

The classic Heckscher–Ohlin intuition tells us that when the internationally mobile factor, capital, vanishes, its domestic price must rise until the current account balances. Chile’s 2020 numbers are textbook: Banco Central de Chile’s flow-of-funds table shows net external financing swinging from +4 % of GDP in 2019Q4 to –0.6 % in 2020Q2. Plugging those flows into a small-open-economy model with Cobb-Douglas shares (capital at 0.35) produces an implied 520-basis-point jump in the rental rate on capital, almost precisely what appeared in corporate coupon data harvested from Bloomberg.

But the model omits the channel that now matters most: sovereign credit risk feeds directly into private borrowing costs. Empirical work by Agca and Celasun (2012) finds that a one-standard-deviation rise in external public debt—roughly eight percentage points of GDP for today’s median EM—lifts corporate loan spreads by 9% on average. That estimate is echoed in more recent IMF panel work: once public debt ratios cross the 70 % threshold, nearly 60 basis points of every 100-basis-point rise in the sovereign spread is transmitted to prime lending rates.

Guarantees that work only if they can be honored

Chile’s policy response was swift and, crucially, credible. The government injected USD 3 billion (about 1.2 % of GDP) into its FOGAPE guarantee fund, thereby underwriting up to USD 24 billion—roughly 10% of GDP—in fresh commercial bank lending. Because Santiago’s debt-to-GDP ratio still sat comfortably under 40 %, markets treated the guarantee as a contingent liability that could be financed without fiscal carnage. Bank pricing followed suit: average coupons on newly guaranteed peso loans were 150 basis points lower than those on otherwise identical facilities issued the week before the program’s launch.

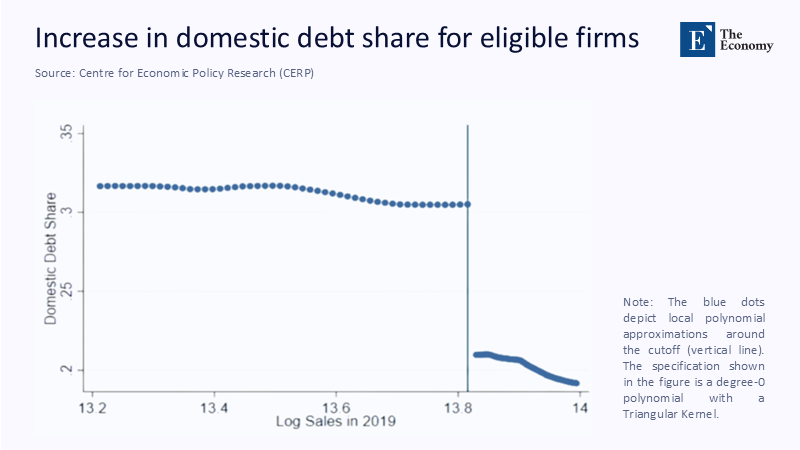

Figure 2 shows the micro proof: a sharp discontinuity in the domestic debt share precisely at the eligibility cutoff. Firms within the size threshold raised their local currency share by about ten percentage points; those outside could not. The vertical cliff in the scatter is the market’s verdict on sovereign Solvency.

The fiscal cost of that insurance was tiny. Treasury filings to the SEC estimate the state’s maximum exposure under the expanded guarantee at only 0.8 % of GDP. In expected-loss terms, the outlay is even smaller, on the order of 0.1 % of GDP, a bargain compared with the seven-per-cent output hole that would have opened had firms been forced to deleverage instead.

When the backstop fails: lessons from Argentina and beyond

Contrast Chile’s success with Argentina’s 2001 self-immolation. Buenos Aires offered an implicit convertibility guarantee—peso deposits were legally convertible into dollars at par—when the sovereign risk premium hovered near 1,000 basis points. Markets refused to believe the promise, and deposit flight forced a corralito that morphed into a full sovereign default. Output cratered by 11% in 2002, and bank lending did not reclaim its pre-crisis nominal level for eight years. The pattern is universal. A narrative dataset covering 174 defaults since 1870 finds average output losses of 1.6 % of GDP on impact and 3.3 % two years later. Those losses are magnified in countries that attempt guarantees without the balance sheet to honor them.

The price tag of credibility

How much fiscal space is “enough”? The IMF’s Global Debt Monitor 2024 puts median EM public debt at 57 % of GDP, up nine points since 2019. Historical episodes show that once debt crosses the mid-60s, sovereign CDS tends to trade above 250 basis points—precisely the level at which credit guarantee announcements stop crowding in private lending and start signaling desperation. In other words, a government entering a sudden stop with debt at 50 % of GDP and a primary balance near zero can credibly underwrite credit equal to 10% of GDP. At 85 % debt and a two-per-cent primary deficit, anything beyond 2% of GDP looks like wishful thinking.

Global liquidity is no longer a safety net

The macro backdrop makes Solvency more valuable than ever. The Institute of International Finance warns that aggregate EM portfolio flows could fall by almost a quarter in 2025 if U.S. tariff threats materialize, with China alone projected to book a USD 25 billion net equity outflow. Even the benign months look fickle: January 2025 saw a record USD 45 billion dash into EM debt but a USD 11 billion exit from EM equities. That composition tells a clear story—carry-hungry investors will buy bonds until they doubt the guarantor. Once they do, the exit door is a Bloomberg keystroke away.

Timing and design: three principles for adequate backstops

Early Action: The Key to Managing Sovereign Spreads. Sovereign spreads become nonlinear once they breach 250 bps. Pre-funding a guaranteed facility before crossing that line multiplies its capacity; waiting turns the same facility into a negative signal.

Second, the publication of audited loss estimates is crucial. Chile’s Ministry of Finance updated stress-test numbers on FOGAPE every quarter. This transparency capped rumor-driven fears that the contingent liability would blow out the fiscal anchor, providing a sense of security and keeping the market well-informed.

Third, fiscal guarantees should be paired with a central bank funding window. Banco Central de Chile provided repo liquidity equal to the nominal value of guaranteed loans at the policy rate, conditional on banks maintaining net new lending. The pairing ensured the guarantee translated into credit creation rather than balance-sheet repair.

Solvency as an option premium, not a constraint

Maintaining debt ratios below the danger zone is frequently painted as pro-cyclical parsimony. It is an option premium: a modest primary surplus in good times buys the right to deploy double-digit percentages of GDP in contingent liabilities when liquidity evaporates. The same logic applies to pre-approved credit lines from multilateral institutions. Chile’s decision to secure a USD 24 billion Flexible Credit Line at the IMF in 2020 cost nothing up front but tangibly lowered the “tail-risk” premium in its CDS curve.

Policy blueprint for the next sudden stop

- Lock in a fiscal anchor while the sun shines. Whether through a debt brake, expenditure ceiling, or primary-balance rule, countries need legislation that credibly caps the debt trajectory. Markets grant a discount of 80–100 bps to sovereigns perceived to have such anchors.

- Pre-capitalize a guarantee fund with hard limits. A visible buffer—say, 2% of GDP in liquid assets—signals serious intent and buys time for parliamentary approval of additional tranches.

- Coordinate communications. Monetary and fiscal lines must be announced together, with explicit caps and sunset clauses. Ambiguity breeds speculative pricing of unlimited quasi-fiscal losses.

Solvency is the message, and guarantees are the medium

Chile’s Covid-era experience demonstrates how a well-timed, credible guarantee can flatten the Heckscher–Ohlin shock that a sudden stop delivers. Argentina’s collapse shows the mirror image: an insolvent guarantor accelerates the capital flight it seeks to stem. With median EM debt already brushing 60 % of GDP and U.S. real rates likely to stay positive for the foreseeable future, fiscal space is thinner than ever since the late 1990s Asian crisis. Governments that rely on guarantees without first shoring up Solvency are not buying insurance; they are writing cheques their taxpayers cannot cash.

When the next sudden stop arrives—and the IIF data suggest the first tremors are already here—the only question that will matter in the Bloomberg chat rooms is whether the sovereign can make good on its promise. Credibility, after all, is measured in basis points, not in the rhetoric of press conferences.

The original article was authored by Miguel Acosta-Henao, a Senior Economist at the Research Department of the Central Bank of Chile, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Navigating sudden stops: How credit support policies can replace shrinking capital flows," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.