Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Each time the monetary wheel skids on an oil slick or a pandemic, policymakers rediscover a deceptively plain lesson: the cheapest way to purchase stability is to promise prices will rise at roughly two percent a year—and then keep that promise when it hurts. The target, born of New Zealand pragmatism in 1989, has since outlived monetarism’s collapse, two rounds of quantitative easing, and the fiercest inflation shock in half a century. Its persistence is neither accidental nor merely traditional; it rests on a documented record of disinflation that proved more durable than skeptics expected and on a sober recognition of the institutional cost of abandoning an anchor once it has been earned. Recent cross-country evidence only sharpens the point: despite differing initial conditions, economies that tied policy credibility to an explicit numerical goal have experienced both faster convergence toward low inflation and smaller swings in long-run expectations, underscoring why the political bargain behind the two-percent compass keeps winning renewal even after brutal market tests.

A Picture Worth Ten Models

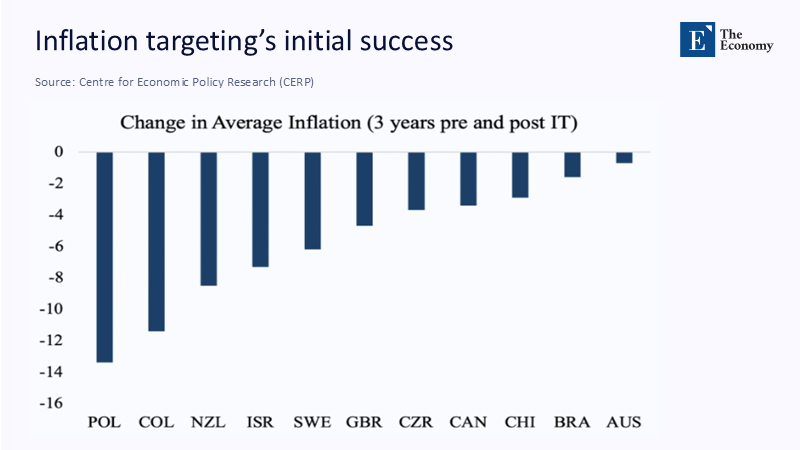

Figure 1 distills the first wave of inflation-target arrivals: within three years of adopting explicit targets, pioneers such as Poland, Colombia, and New Zealand shaved six to fourteen percentage points off their average inflation rates. The histogram, stark in its negative bars, makes it easy to see why the early 1990s were dubbed “the credibility bonus decade.”

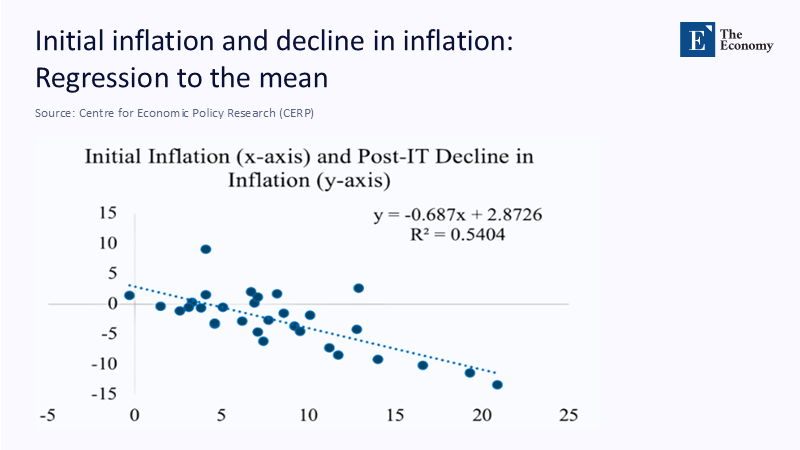

Yet Figure 2 complicates the triumphalist take. The downward-sloping scatter, with a slope of –0.69 and an R² of 0.54, tells us that fully half the observed disinflation can be predicted by a mechanical regression-to-mean effect: the hotter a country was running at baseline, the faster inflation was bound to cool, targets or not. An honest analyst must, therefore, concede that part of what looked like policy magic was statistical gravity.

Those twin insights explain a puzzle that has shadowed the literature since the CEPR’s first forensic audit of IT regimes. Suppose the “before-and-after” pictures are so impressive. Why does a synthetic-control comparison (matching each adopter to a non-adopting twin) show only six of the twenty-three targeters beating their control groups with statistical significance? Figure 2 provides the missing piece: the counterfactual world was cooling anyway, pulled down by the same global disinflationary tide—cheap Chinese goods, older demographics, and a dollarized commodity complex—that Alan Greenspan once called a “global glut of production capacity.” The real virtue of an explicit target, then, was not the magnitude of the initial drop but the durability of the anchor once the tide turned.

From Monetarist Steering Wheels to Price-Level Compasses

The 1970s monetarist adventure is best remembered for its abrupt end. Confronted with a pair of energy shocks, the Federal Reserve in 1979 set monetary aggregate limits that proved simultaneously too rigid for the banking system and too porous to restrain velocity. When real GDP contracted three quarters, and prime lending rates topped 21%, even Milton Friedman admitted velocity was “behaving most erratically.” September 1982 FOMC minutes read like a capitulation: the Committee would henceforth steer by the federal funds rate but keep an eye on headline prices. That half-step opened the conceptual door for the first explicit inflation target, legislated seven years later on the other side of the world. The genius of the Kiwi invention was its communicability: price changes were a kitchen-table concept, unlike M1 or the base.

Early Success, Nuanced Evidence

Figure 1 spotlights the dramatic early wins, yet the numbers are more nuanced once set beside Figure 2. Poland’s eye-catching 14-point plunge came off a pre-target average near 31%; even without IT, textbook convergence dynamics would have pushed the rate lower as post-transition wage demands cooled. Israel’s seven-point drop followed a 1985 heterodox stabilization that had already broken a triple-digit spiral. To isolate the causal bite of the target, one must look not at the size of the fall but its stickiness. On that score, CEPR researchers Bhalla, Bhasin, and Loungani find that targeters saw volatility decline by roughly a third compared with peers, even when average inflation rates converged. In other words, IT’s killer app was to cut the variance of surprises, the thing that robs relative prices of informational value.

QE, the ZLB, and the Search for Higher Targets

Fast-forward to 2009, the world’s leading central banks were running balance sheets that were once thought unimaginable: the Fed at 35% of GDP and the Bank of Japan above 100%. Critics from the Peterson Institute through the Bank for International Settlements argued that a higher steady-state inflation goal (3%) would raise nominal interest-rate ceilings, reducing the odds of hitting the zero lower bound. But market expectations betrayed scant faith in that thesis. Five-year-five-year forward breakevens, which strip out short-term noise, hugged 2% for most of the QE era. The models missed that credibility acts as insurance: when investors believe tomorrow’s central bankers will still care about the same target, the real equilibrium rate tilts upward, buying extra room without revising the mandate.

COVID-19, Supply Marathons, and a Seven-Point Climb

The pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine delivered the single most significant supply-side stress test since the 1970s. U.S. CPI leaped from 0.2% to 9.1% in barely two years; the euro area hit 10.6%. The public conversation flirted again with raising the target: Financial Times op-eds framed it as a “lesser evil” versus recession, and even some former Fed staffers queried whether 2 % made sense in a de-globalizing world. Yet the episode’s endgame vindicated the old rule. By April 2025, headline inflation in all G7 economies had returned to 2–3%. Using the Fed’s standard sacrifice-ratio estimate (1.5), the cumulative cost of that seven-point disinflation is roughly 10% of one year’s U.S. GDP—painful but barely a third of the Volcker episode and far less socially regressive than the multi-year inflation tax a higher target would have legitimized.

Reading the Figures Together

Figures 1 and 2, interpreted jointly, offer a compact parable. First, an explicit target can catalyze rapid adjustment when expectations are loose. The second reminds us that nature does some of the work. The policy adds an ironclad terminal condition: prices will not drift indefinitely but converge toward a point understood by households and bond traders alike. That promise, renewed daily across speeches and dot plots, pins long-run expectations even when short-run gyrations look frightening. Surveys corroborate the message: the ECB’s five-year median inflation expectation never climbed above 2.3% at the height of Europe’s energy crisis, and the New York Fed’s consumer survey has recently dipped below 3 % for its three-year horizon.

Why Not Three or Four Percent?

Economists who favor a higher target usually cite two arguments: (1) measurement bias inflates reported CPI, so proper inflation is lower, and (2) a bigger nominal buffer gives monetary policy more conventional ammunition. Yet both points stumble on political economy. If citizens distrust the yardstick, raising the target doubles the distrust. As for weapons at the zero lower bound, recent work by Rachel and Summers puts the real neutral rate for the United States near 0.75%—a figure that rises when inflation expectations are better anchored. Under that arithmetic, a 2% target implies a 2.75% nominal neutral rate, providing room for 275 basis points of cuts before zero. A move to 3% would shift the nominal neutral only marginally because the real rate response would partially offset the increase. Put bluntly, the gain is theoretical, and the credibility cost is immediate.

Flexible Orthodoxy for a Shock-Prone Century

If the target number stays put, the instruments around it must grow more agile. Three strategic upgrades are already visible:

- Balance-sheet Elasticity—The 2023 banking tremor proved that central banks can shrink aggregate reserves while simultaneously lending to fragile nodes. Lender-of-last-resort facilities thus become shock absorbers, not directional signals.

- Macro-Prudential Firewalls—Countercyclical capital buffers, borrower-based mortgage caps, and sectoral risk weights allow policymakers to cool speculative froth without bludgeoning the whole demand complex.

- Probabilistic Forward Guidance – The Fed’s Monetary Policy Report now presents fan charts rather than point forecasts, admitting uncertainty while nailing down the central path: PCE inflation “will be returned to 2% over time.”

These tools amount to flexible orthodoxy: Everything except the anchor itself can be adjusted. In this view, the central bank is a sailor who trims sails, shifts ballast, and even changes masts but never tosses away the compass.

Full-Circle Back to 1989

A neat symmetry closes the narrative. In 1989, New Zealand’s 0–2% band looked radical; in 2025, it feels nostalgic. The intervening years, captured in the twin charts above, confirm that when the world wobbles, it is cheaper to press reset on two-percent credibility than to rewrite the contract. Economies that adopted and stuck to the rule enjoyed less volatile real growth, lower-interest-rate risk premia, and smaller wage-indexation spirals. Those outcomes are not visible in the slope of money-demand curves nor textbook policy rules but in the quieter corners of Figure 1: see how even Australia and Brazil, the lightest decliners, still posted negative bars—evidence that inertia bends when expectations bend first.

Evidence Is Stubborn

The debate will re-ignite with every shock—climate, geopolitics, or the next pandemic—but the historical ledger now spans half a century, two great crises, and the most significant supply crunch since OPEC. The entry marked 2% balances costs and benefits more persuasively than any alternative number on offer. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate both the immediacy of the payoff and the subtle statistical caveats, yet they also dramatize a deeper point: credibility, once earned, behaves like compound interest. Break the promise, and the future becomes more expensive; keep it, and the next crisis comes at a discount. Until another framework survives as many controlled explosions, the modest-sounding 2% target will remain the monetary world’s most reliable line in the sand—never carved in marble but etched more deeply each time events try to erase it.

The original article was authored by Surjit S. Bhalla, currently the Chairperson of the newly constituted GOI-Mospi committee to estimate Household Income Distribution in India. The English version of the article, titled "An assessment of the performance of inflation targeting," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.