Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

By 2025, the cost of creating a convincing digital lie will be lower than the cost of correcting it. This shift in the battleground raises a crucial question: Can democracies effectively counter disinformation without compromising their freedoms? The urgency of this threat cannot be overstated.

Disinformation’s Leap from Fringe Nuisance to Kingmaker

When the World Economic Forum polled 1,490 global risk experts on the most pressing dangers for 2024-26, the rise of AI-generated misinformation and disinformation was ranked as the top threat. This was seen as capable of triggering a significant crisis within two years. With its high social media usage and internet reliance, Japan is particularly vulnerable to this prediction.

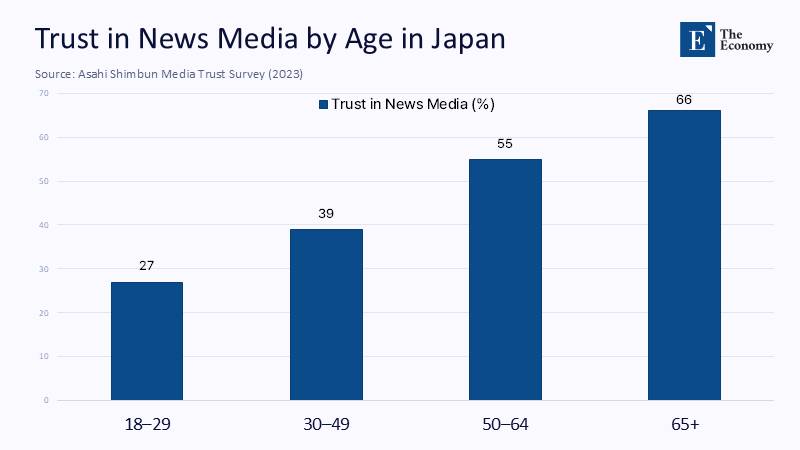

The political consequences are already shown: during the 2018 Okinawa gubernatorial race, fabricated opinion polls masquerading as Asahi Shimbun exclusives flooded messaging apps, reaching hundreds of thousands of voters before mainstream outlets could debunk them. In the January 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake, rumors that “foreign looters” were raiding evacuation centers crescendoed on X within hours of the first aftershocks, forcing police to spend scarce emergency bandwidth refuting ghost crimes. Each viral lie chips away at turnout and trust: an Asahi survey shows 70% of Japanese under forty say they “do not trust politics,” a skepticism rate thirty points higher than their grandparents’ generation. In a climate of endemic suspicion, even a distorted video can swing a close mayoral race—and mayors are where national coalitions are seeded.

Counting the Externalities of One Viral Lie

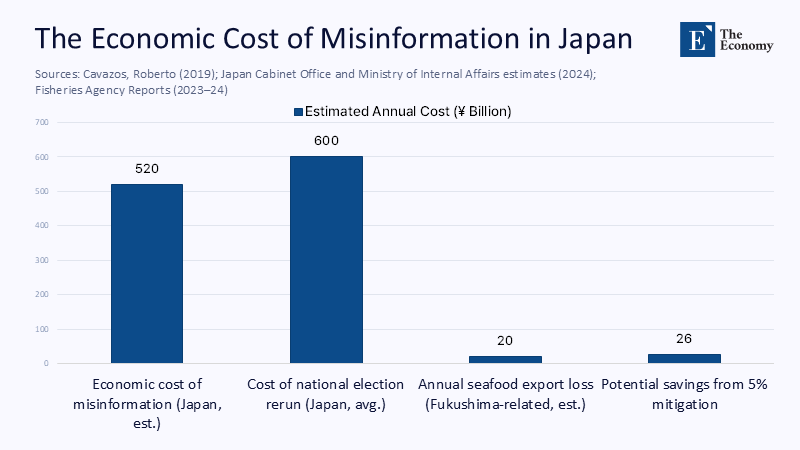

The economic drag of disinformation is no longer speculative. A 2019 study by economist Roberto Cavazos pegged worldwide losses from fake news at US $78 billion a year; analysts at HKU Business School argue that figure understates the present toll because it predates generative AI. Japan’s 2024 GDP sits near US $4.3 trillion; scaling the Cavazos ratio places the domestic hit around ¥520 billion annually. By contrast, staging a nationwide House of Representatives election costs the treasury roughly ¥600 billion each time, according to Internal Affairs Ministry audits of the 2017 and 2021 cycles. If corrosive narratives obliged even one extra snap poll per decade, the fiscal bleed would rival the education budget of a mid-size prefecture.

Ad dollars compound the loss. A 2024 NewsGuard-Comscore analysis estimates that programmatic advertising quietly channels US $2.6 billion annually to publishers of misinformation worldwide. Japan’s share of global digital-ad spend suggests roughly ¥20 billion in local corporate money is underwriting sites designed to undermine the same companies’ reputations—capital that could otherwise bankroll original journalism. Meanwhile, Beijing’s seafood ban, triggered by a state-amplified narrative that Fukushima wastewater was “radioactive,” erased about ¥20 billion in export revenue for fishing cooperatives within six months. Every hoax has a balance sheet line.

Historical Echoes: When Monarchies Fell to the Rumour Mill

The idea that lies can feel regimes predates the algorithm. In eighteenth-century France, the underground pamphlet trade of libelles portrayed Marie Antoinette variously as a profligate harlot and a foreign agent; historians still debate how decisively those broadsheets eroded the monarchy’s legitimacy in the decade before 1789. Half a century later, the Tsarist secret police plagiarized earlier anti-Semitic tracts to produce The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a forgery that metastasized across Europe and the Middle East, fuelling pogroms and conspiracy theories that survive online today.

These precedents matter because they expose a constant: suppressing rumors by brute force rarely works and often backfires, reinforcing perceptions of guilt. Louis XVI’s censors confiscated slanderous leaflets, yet the more they seized, the more sensational new editions became. The Okhrana’s covert fabrication likewise demonstrated that a state that muddles the information pool for tactical gain inevitably poisons its credibility. The lesson for twenty-first-century Japan is clear: the cure must not look like the disease.

Singapore’s Shadow and the Hazard of Overcorrection

Japan’s constitution sharply limits prior restraint, but policymakers frustrated with the viral speed of falsehoods occasionally glance admiringly at Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act. POFMA empowers ministers to order “corrections” or takedowns within hours, and non-compliance invites crippling fines. Yet a 2024 Human Rights Watch country report concludes the statute has been wielded repeatedly against opposition figures and independent outlets, cultivating a climate of self-censorship. Singapore’s contact-tracing app TraceTogether became a similar cautionary tale when police access to logs, promised initially to be health-only, was quietly authorized under the Criminal Procedure Code, jolting public trust.

For Japanese voters who endured wartime thought-control laws, the optics of a cabinet minister deciding “truth” on a Friday morning are untenable. The moral is not that regulation is futile but that discretionary censorship invites mission creep. The boundary between inoculation and authoritarianism is only visible when rules are transparent, time-bound, and reviewable by an independent judiciary.

Designing a Precision Mesh: Five Interlocking Defences

Therefore, any viable Japanese strategy must treat disinformation less like a crime to be erased than a pollutant to be filtered at multiple gauges. The proposed defensive mesh rests on five mutually reinforcing layers, each narrow enough to avoid the Singapore trap yet broad enough to impose economic friction on bad actors.

First, statutory transparency triggers would compel platforms exceeding eight million domestic monthly users to publish, during election periods or declared disasters, real-time dashboards of the thousand most-shared political URLs and any coordinated bot networks they disrupt. Sunlight, not takedown, is the remedy, aligning with Diet precedents for financial disclosure.

Second, independent algorithmic audits, financed by a levy on large platforms and overseen by the Personal Information Protection Commission, would quantify amplification bias annually. The results would feed an open-access Diet repository, letting civil society—not ministers—interpret the findings.

Third, a rapid-response civic verification corps would institutionalize the #STOP風評被害 template trialed during the Fukushima water scare when a flagged rumor trends, local broadcasters, meteorological agencies, and trained volunteers would push templated infographics within thirty minutes, turning evidence into viral counter-narrative. Finland’s integration of media literacy drills into the national curriculum has kept it atop the European Media Literacy Index every year since 2018. It illustrates the payoff of marrying state coordination with classroom skepticism.

Fourth, economic disincentives matter. A one-percent surcharge on ad impressions served adjacent to content later judged false by the transparency protocol would generate about ¥5.5 billion a year—money that bankrolls the verification corps—assuming only half a percentage point of Japan’s ¥1.1 trillion social-media ad market is reclassified. Platforms that pre-emptively surface source labels can avoid the levy, internalizing the externality instead of distributing it to society.

The fifth and most coercive, judicially reviewable correction orders—never issued by a ministry—would be reserved for speech that meets the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights threshold of incitement to violence. Plaintiffs, including the state, could petition a dedicated bench of the Tokyo District Court for a 48-hour interim order, with a full evidentiary hearing within ten days. The clock is fast enough to matter online yet slow enough to preserve adversarial processes.

Quantifying the Net Benefit of Precision

Even conservative assumptions suggest the mesh pays for itself. If Japan pares only 5% of the ¥520 billion estimated annual cost of disinformation, the dividend is about ¥26 billion—a multiple of the verification budget. Seafood export shocks alone show how quickly returns accrue: each month of false radiation rumors costs Tohoku fishermen roughly ¥3.3 billion in lost sales. Curtailing such episodes by a quarter nearly recoups a year of audit costs.

Advertising reallocations amplify the upside. NewsGuard calculates that global brands misdirect US $2.6 billion into disinformation domains annually; redirecting even 10% of Japan’s prorated slice toward quality local outlets could fund scores of investigative desks and STEM beat reporters. The mesh nudges chief marketing officers to shift budgets without new speech restrictions by making risk measurable.

Human Capital as the First Responder

No firewall endures if voters cannot parse a doctored video. Yet fewer than 27% of Japanese teenagers say they “always check source credibility,” compared with roughly half of their US peers.

Finland’s curriculum solves that gap by treating fact-checking like a PE skill: pupils learn reverse-image searches alongside algebra, and adults consequently outperform European averages by ten points in spotting deepfakes. Tokyo should earmark a tranche of the ad-levy fund for prefectural education boards, rewarding teachers who upload open-license verification modules and expand NHK’s Verify segments into interactive prime-time challenges. The pedagogical horizon is to normalize skepticism as civic hygiene rather than cynicism.

Liberty through Surgical Intervention

Kyoko Kuwahara’s East Asia Forum commentary warns that Japan must “reboot” its dormant disinformation defenses lest it confronts its 2016-style shock. Rebooting does not require demolishing the house of free speech; it entails swapping blunt instruments for calibrated tools. Transparency dashboards expose reach without silencing voices. Audits translate political hunches into data a court can review. A levy shifts private costs back onto platforms, and a narrowly drawn injunction authority flexes only where violence looms.

The moral geometry mirrors the user’s dilemma. There is a fine line between an agile democracy and a surveillance state, but it is legible when intervention is precise, proportionate, and contestable. Liberty is not the absence of guardrails but the presence of rails wide enough to allow dissent yet tight enough to keep the train from plunging into conspiracy ravines. With its constitutional allergy to prior restraint and technological sophistication, Japan is uniquely positioned to model that equilibrium for the Asia-Pacific. In doing so, Tokyo would prove that yielding a sliver of freedom to targeted scrutiny need not slide into totalitarianism—provided every incision is publicly mapped and democratically stitched. Ultimately, that is how a nation inoculates itself: not by building higher walls but by sharpening the scalpel.

The original article was authored by Kyoko Kuwahara, a research fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs. The English version, titled "Japan must reboot its disinformation defences," was published by East Asia Forum.