Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In classroom after classroom, ministers tell young Italians, Japanese, French, and Koreans that a glossier CV protects against economic drift. Yet the evidence is mounting that investment in human capital in these four economies now outstrips employers' willingness-or ability—to buy it. The scale of the upskilling challenge is immense. Without a corresponding increase in demand, it becomes the policy equivalent of filling a swimming pool with no drainpipe: talent accumulates, stagnates, and, eventually, evaporates.

The Mirage of Tight Labour Markets

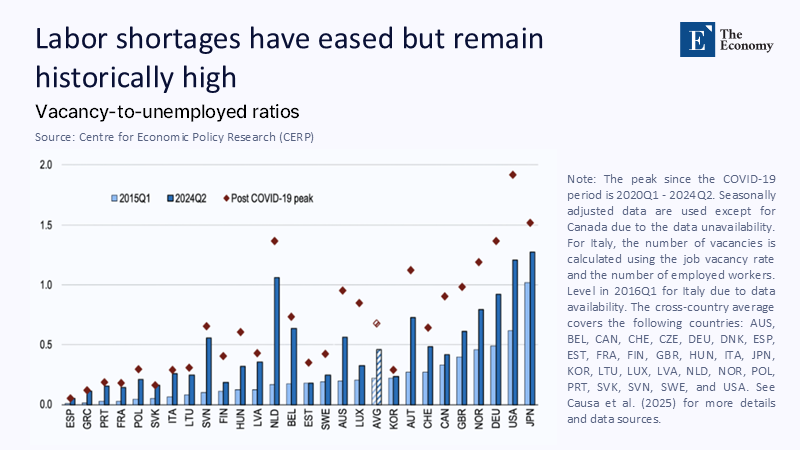

At first glance, figure 1's bars and diamonds look like the reason for optimism: vacancy-to-unemployed ratios in Japan remain above 1.2; France's have doubled since 2015; even Italy edges higher. The chart's power, however, is comparative. While Canada, Germany, and the United States push ratios toward—or past—1.5, signaling genuine bidding wars for labor, the four focus countries cluster at the low end. In Italy and France, barely one vacancy exists for every four job-seekers; in Korea, the ratio flirts with 0.5. The post-pandemic spike in the OECD average, a significant increase in the average vacancy-to-unemployed ratio across OECD countries following the COVID-19 pandemic, comes chiefly from migrant-reliant economies, not our quartet. The upshot is a surplus of people, not of posts. Statistical releases confirm the story: Japan's celebrated jobs-to-applicants ratio of 1.25 has stopped inching up for two years straight, while Italy's vacancy-to-unemployment ratio sits below 0.30, half the German benchmark when demand is so tepid, exhortations to learn Python or master additive manufacturing ring hollow.

Supply Piles Up, Demand Drifts Down

Between 2010 and 2024, tertiary education attainment among 25-to-34-year-olds rose from 19% to 28% in Italy, 48% to 55% in Korea, and 52 % in France. Japan, already above the OECD mean in graduate output, still added another four percentage points. Yet employment growth lagged. Italy's employment-to-population ratio remains at 63%, the second lowest in the Eurozone, despite two record years of GDP expansion. In Korea, monthly job creation fell from an average of 330,000 in 2023 to barely 100,000 in mid-2024. According to INSEE data, France produced 130,000 net jobs last year, but the number of "qualified" positions requiring a university degree declined. These numbers illuminate the core paradox: the supply of credentials has sprinted ahead of the supply of roles that value them.

Incentives and the Rise of the NEETs

When effort fails to convert into prospects, young people rationally switch off—Italy's NEET rate for 15- to 29-year-olds crossed 28 % in 2023. Traditionally below the EU average, France increased to 14%, while Korea still hovers around 18% despite decades of exhortation. Japan's headline NEET figure is lower—4-5%—but its 'Satori Generation', a term used to describe the generation that experienced the economic downturn in the 1990s and is characterized by risk-averse minimalism in which the brightest graduates aim for the smallest footprint rather than the most significant contribution, embodies an equally dangerous disengagement. The labor-economics literature is unambiguous: NEET cuts lifetime earnings by five to ten percent each year spent and drags national productivity down in parallel. Upskilling campaigns that ignore this feedback loop condemn themselves to shrinking marginal returns.

Job Quality: The Silent Deal-Breaker

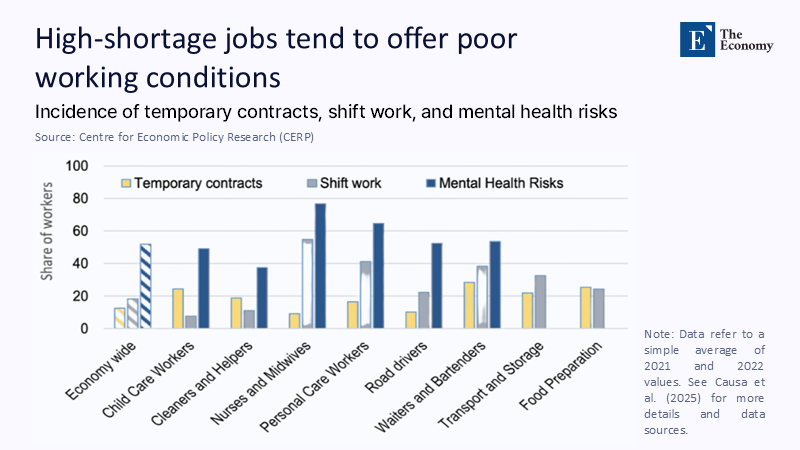

Readers can see in Figure 2 that shortages cluster in occupations—personal care, waiting tables, transport—where temporary contracts and mental-health hazards run two to five times the economy-wide average. Italy's labor inspectors report that 62 % of new hires in hospitality last year were on contracts shorter than six months; in Korea, half of all twenty-somethings employed in retail have no social insurance coverage. France's shift-work incidence tops 50 % among personal-care workers, and Japan's care-home staff face the region's highest recorded levels of workplace pressure, a discrepancy that fuels chronic vacancies even in a country famed for its work ethic. When graduates examine such conditions, they update their cost-benefit calculus swiftly, often by waiting out the market at home.

Gender, Migration, and the Demand-Side Lens

The CEPR analysis reminds us that women and immigrants disproportionately fill vacancies in low-pay sectors. In Italy, migrants constitute 160 % of their share of the overall workforce in accommodation and food services, while women's representation in health nearly doubles their economy-wide weight. This matters for the four focus economies in two ways. First, Japan and Korea—countries with historically low female participation—could relieve shortages and raise job quality by lifting barriers around parenting, tax, and contract rigidity. Second, reliance on migrants, the solution adopted by the U.S. and Germany, is politically and administratively tougher for states with linguistic homogeneity and restrictive naturalization rules. For them, the only sustainable fix is to expand decent domestic demand.

Demographic Gravity: Falling Supply Cannot Save a Weak Market

Demographers project that, by 2035, the working-age population will shrink by 13% in Italy, 10% in France, 15% in Korea, and 17 % in Japan. Classical economics predicts that as supply falls, wages rise, and unemployment melts away. But that elegant mechanism assumes labor demand is exogenous. In reality, firms anticipating smaller domestic markets are already throttling back investment. As a share of GDP, OECD data show that gross fixed capital formation, which refers to the total value of a country's physical assets such as factories, machinery, and infrastructure, averaged 20% in Germany and 22% in the U.S. during 2021-23, but only 18 % in France, 17% in Korea, and a paltry 16 % in Italy. Japan's rate, chronically low since the 1990s, slid to 14% last year, barely half the 1989 level. Until capital outlays revive, demographic tightening will mostly trim the quantity of low-quality jobs, not bid up the quality of high-skill ones.

Policy Myopia: Why Supply-Side Remedies Keep Misfiring

Faced with headlines about "skills gaps," policymakers double down on vouchers, coding boot camps, and re-skilling credits. Yet training subsidies cannot force companies to raise offers. Worse, each fresh cohort of publicly financed trainees that fails to locate rewarding work undermines faith in the social contract. In Italy, 40 % of 2022 Digital Jobs Fund participants were still searching nine months after certification. During its first two waves, Korea's vaunted K-Digital Training program placed barely half its graduates into regular positions. France's Compte Personnel de Formation, a portable training credit introduced with fanfare in 2019, spends €2 billion a year but has yet to dent the youth inactivity rate. And Japan's long-running Hello Work centers now list more low-pay care openings than professional vacancies, a ratio that quietly discourages university alums from even logging on.

A Demand-Side Agenda: Turning the Telescope Around

If the diagnosis is demand deficiency, the remedy must work on demand. Three levers stand out.

Predictable public investment. Italy's NextGenerationEU allocation, if channeled into the rail and green construction, gives firms a visible multiyear project pipeline; Webuild's in-house academies already train 2,000 workers a year for high-spec tunneling jobs. Scaling that model across energy retrofits and grid upgrades could absorb tens of thousands of mid-skill Italians while raising the ceiling on wages.

Labor-market dualism reform. Korea's two-tier system makes permanent contracts 30 % more expensive than temporary ones, so employers cap core staff and load extra work onto auxiliaries. Equalizing and enforcing social—insurance contributions would shrink the casual wage discount, nudging firms to offer stable roles that justify higher skill acquisition.

Early-career wage compression. Japan's seniority pay keeps entry salaries low; raising them would increase the net present value of skill investment. A two-percentage-point cut in payroll tax on workers under 30, financed by phasing out the spousal-income tax deduction that suppresses female hours, would be broadly revenue-neutral yet sharply pro-participation.

What the Migration Champions Teach

Germany and the United States are often hailed as models because immigration props up their labor force. However, immigration succeeds only because each country pairs it with robust job creation. Germany maintained capital-formation rates above 20% of GDP even in 2023's energy crunch, and the U.S. pumped public money into semiconductors and renewables, generating immediate vacancies that new arrivals could fill. Transfer the migrants without the vacancies, and the formula fails. For culturally homogeneous or migration-averse societies like Japan, Italy, and Korea, stimulating private investment is not a nice-to-have but a demographic necessity.

Country-Specific Playbooks

Italy. Streamline corporate tax credits for R&D, currently split across five overlapping schemes, into a single five-year commitment pegged to employment targets. Pair it with accelerated depreciation for equipment installed in the South, where out-migration among graduates is highest.

France. Convert the multiplicity of youth-employment subsidies into one hiring bonus that escalates with contract length and skill level. Link the bonus to regionally negotiated "employment compacts" that bundle transport links and affordable housing around target clusters.

Korea. Pass the long-stalled Irregular Worker Protection Act. Evidence from longitudinal employment surveys shows that the wage premium for a permanent contract is now 34 %—double the gap in 2005. Closing it would raise lifetime returns to training faster than any voucher.

Japan. Offer a time-limited tax credit to companies that reduce the share of non-regular workers below 20 % of total staff and simultaneously raise first-decade wage profiles. Tie credit eligibility to measurable productivity gains, ensuring the reform fosters efficiency, not just cost transfer.

Skills and Seats, or Neither

The most durable economic myth of the past quarter-century is that education alone can outwit global competition. In truth, education is a conditional asset: it boosts growth only when employers are ready and willing to hire educated workers into productive roles. Japan, Italy, France, and Korea are now confronting the boundary of the supply-side policy frontier. Unless they engineer a genuine revival of demand through investment, labor-market reform, and early-career wage support, the surplus of skills they produce will curdle into cynicism, inactivity, and decline. The choice is not between upskilling or job creation but between delivering both together or watching both slip away.

The original article was authored by Orsetta Causa and Emilia Soldani. The English version of the article, titled "When upskilling is good but not enough: Understanding labour shortages through a job-quality lens," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Causa, O., D. Luu and D. Quinn (2025), "When upskilling is good but not enough: Understanding labour shortages through job quality." OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper No 298. (Underlying source for Figures 1 and 4 in the present column.)

European Commission (2024), "Italy: Progress of the Recovery and Resilience Plan – Autumn 2024 update." Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, Brussels.

Eurofound (2024), "Living, working and COVID-19 in France: 2024 survey." Dublin.

Eurostat (2024a), Job Vacancy Statistics (JVSQ_NACE_R2). Data extracted November 2024.

Eurostat (2024b), Employment Rate – Age Group 20-64 (LFSA_erge). Data extracted December 2024.

International Monetary Fund (2024), "Republic of Korea: 2024 Article IV Consultation—Staff Report." IMF Country Report No 24/122.

International Monetary Fund (2023), "Republic of Italy: Selected Issues – Labour-market slack and vacancy-unemployment dynamics." IMF Country Report No 23/191.

INPS – Istituto Nazionale Previdenza Sociale (2024), “Rapporto annuale sulla vigilanza e sui contratti atipici.” Rome.

INSEE – Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques (2024), "Emploi et population active – Résultats du 2ᵉ trimestre." Paris.

Istat – Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (2024), “Forze di lavoro: Dati trimestrali destagionalizzati.” Rome.

Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2024), "General Employment Placement Status (Hello Work), October 2024." Tokyo.

Jang, S. H. and Y. S. Park (2023), "Labour-market dualism in Korea: What next for reform?" KDI Policy Study No 2023-06.

Korea Statistical Information Service (2024), Economically Active Population Survey – Monthly Series. Accessed December 2024.

Korea Ministry of Employment and Labor (2024), "Employment Trends and Policy Brief – September 2024." Seoul.

OECD (2024a), Employment Outlook 2024. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (chapters 1 & 2 for vacancy ratios and job-quality metrics).

OECD (2024b), Taxing Wages 2024 – Comparative Statutory Payroll Tax Indicators. Paris.

OECD.Stat (2024), Educational Attainment and Labour-force Status, Age 25-34. Extracted November 2024.

Statistics Bureau of Japan (2024), Labour Force Survey – Annual Averages 2023. Tokyo.

Webuild S.p.A. (2024), "Academy Report: Skills for Next-Generation Infrastructure." Milan.

Woke Waves Magazine (2024), "The Satori Generation: Minimalism, economic caution and Japan's disengaged youth." Woke Waves vol 4, issue 2, pp 12-18.

World Bank (2024), World Development Indicators – Gross Fixed Capital Formation (% GDP). Data download January 2025.