Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

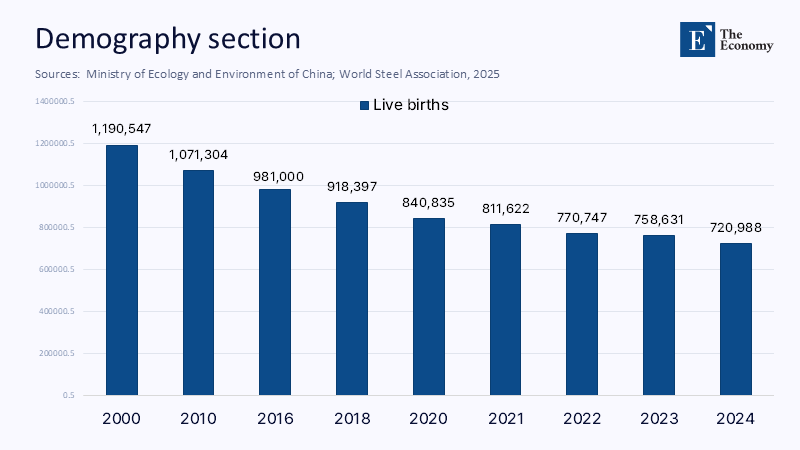

Tokyo's neon glow is powered by a labor market adding fewer newborns yearly than Yangon or Sofia. Just 720,988 babies were registered in 2024, the ninth straight annual record low, and Japan's fertility rate has slipped to 1.20, a level at which each generation is scarcely half the size of the one before it. This is not just a demographic trend, but a pressing crisis. At today's labor-force participation rates it signals a net loss of roughly 650,000 workers per year—more than the entire corporate payroll of Panasonic—unless the country recruits talent from abroad. The central thesis of this column is blunt. Without a wholesale embrace of foreign labor and a simultaneous demolition of the corporate practices that waste human capital, Japan's economic base will erode faster than any plausible boost in fertility can repair.

Dead-Centre of the Demographic Vortex

Japan's population pyramid has inverted so sharply that analysts now describe it as an "upside-down kite." Citizens aged 65 or older already exceed 30% of the total, while the cohort aged 20–39 has fallen below 20%.

Internal projections by the Ministry of Internal Affairs show that the working-age population is contracting by nine million this decade, which implies that every five retirees will soon be replaced by only two new entrants to the labor market. The usual cultural explanations—women marrying late, men opting out of marriage—mask deeper structural choke-points. Median condominium prices in Tokyo have tripled since 2000, childcare centers still close at 5 p.m., and the tax code penalizes secondary earners, most of them women. Thus, childbirth has become a rational casualty of a wage structure that rewards tenure, not skill, and of an urban ecosystem calibrated for single breadwinners of the 1970s. The feedback loop is merciless: pessimism about career trajectories depresses marriage, which suppresses births, tightening the labor supply that funds pensions and public services, reinforcing the very pessimism that began the cycle.

Productivity's Paper Ceiling

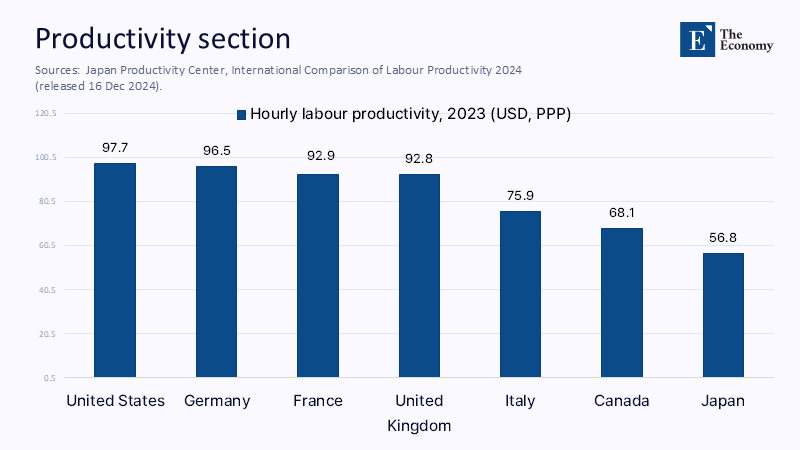

If a shrinking headcount were offset by soaring efficiency, Japan could coast. Instead, output per hour lags the developed world. The Japan Productivity Center puts 2023 hourly labor productivity at US $56.80, ranking 29th among the 38 OECD economies and just 58.1% of the US figure. That gap has widened over two decades: in 2000, Japan delivered 70% of US hourly output; by 2010, the ratio was 65%, and it is now under 60. The metrics expose a wider malaise. Japan's celebrated robotics exports mask an economy where small and mid-sized firms—responsible for 70% of employment—invest less than half the OECD average in digital capital. Productivity growth in services, which employ three-quarters of Japanese workers, has been virtually flat since 2014, meaning hardware miracles in one sector are being canceled by procedural sclerosis elsewhere. Unless the denominator—hours—can be reduced without sacrificing the numerator—value added—Japan will continue to slide down the global league table.

The Collapse of the Overtime Bargain

The post-war compact that allowed weak productivity to persist was simple: work longer. In 2023, Japanese employees still logged about 1,607 hours apiece, compared with 1,342 in Germany, even after decades of legislative nudges to shorten the work day. But the arithmetic no longer works. An aging labor force cannot shoulder endless overtime without courting karōshi-level health risks, and younger recruits, who now receive job offers from remote-first multinationals, demand predictable schedules. Every retiree, therefore, removes not only a day-shift worker but also the overtime buffer that once disguised inefficiency. The result is a double cost: lost output and skyrocketing healthcare liabilities tied to exhaustion-related illnesses. Japan is discovering that endurance is a finite substitute for productivity.

How Legacy HR Is Strangling Corporate Metabolism

Behind the statistical lag lies an archaic wage grid. The seniority-based pay spine, conceived in the 1960s, assumes an endless pipeline of graduates willing to trade early-career underpayment for late-career security. That contract collapses when the pipeline dries up. Promotion decisions remain locked inside opaque committees where loyalty still trumps competence, discouraging lateral hires, female returnees from childcare, and—critically—foreign mid-career specialists who cannot afford to spend fifteen years climbing the ladder. A recent announcement by Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation that it will scrap seniority pay is a breakthrough because it is so rare; most boards fear undermining the prestige that validated their careers. The opportunity cost is staggering: McKinsey modeling suggests replacing seniority pay with competency-based bands could lift service-sector productivity by up to 15% within five years, more than double the annualized effect of incremental robotics investment. Yet resistance persists because altering HR architecture is seen as the final repudiation of the post-war social contract. However, these reforms are necessary for Japan's economic survival.

Immigration as Economic Infrastructure—Not Charity

The numbers speak for themselves. Official registers show 2,048,675 foreign workers on Japanese payrolls at the end of 2023, a 12.4% increase in a single year, but still a mere 3% of total employment. The Ministry of Justice counts 3.77 million foreign residents, or just over 3% of the population, compared with 13% in Germany and 18% in Canada. Japan's new "Specified Skilled Worker" visa, launched in 2019, aimed to recruit 345,000 workers across 14 shortage sectors over five years, but fell short of that goal by its 2024 deadline. Policymakers have responded with a forthcoming revision allowing top-tier SSW-2 holders to stay indefinitely, a move that even once-cautious editorialists at Bloomberg see as a step towards a more open immigration architecture. But this is not just a step; it's a leap Japan needs to take. With birth-and-death trajectories, Japan needs roughly three million additional workers by 2035 to keep the dependency ratio from breaching 80%. No combination of fertility incentives or robotic substitution can fill that gap. Immigration is not just an option; it's a necessity, an economic infrastructure as essential as the Shinkansen or fiber-optic backbones.

Building a Merit-Based Human-Capital Engine

Opening the door, however, will fail if new arrivals are funneled into the same low-mobility channels that trap domestic talent. Reform has to be cut three ways. First, replace tenure pay with transparent competency bands benchmarked to international standards so that a Filipino nurse or an Indian coder can map a plausible five-year career before buying a one-way ticket. Second, legislate complete portability of pension credits and unemployment insurance across borders; Singapore's Central Provident Fund offers a template in which foreign professionals accumulate benefits they can cash out when they leave. Third, saturate prefectural polytechnics with English-medium programs keyed to forecast deficits—elder care in Miyagi, precision welding in Aichi, and cloud security in Fukuoka. Digital one-stop portals should let employers complete the entire visa onboarding sequence in under 48 hours, matching the performance of Estonia's e-residency system. Such administrative velocity is not a luxury but a competitive necessity: the yen's weakness already erodes Japan's wage premium vis-à-vis Vietnam and Thailand, countries that now compete for the same nurses and software engineers.

Neighbor as Case Study: Korea's Parallel Dilemma

South Korea offers a real-time control group. It still logs 1,896 hours per worker—almost 300 more than the OECD average—yet its labor productivity growth has slowed to about 1%, even after blanket 52-hour work-week legislation. Seoul's boards mirror Tokyo's reluctance to entertain mid-career lateral hires, and their efforts to cap overtime merely shifted tasks into unofficial shadow hours or exported them to subcontractors. The message is clear: shaving hours without dismantling seniority structures yields cosmetic gains at best. If Japan liberalizes immigration but fails to modernize HR—from evaluation rubrics to language policy—it will replicate Korea's frustrations: more bodies but no surge in value added. Conversely, a functioning meritocracy multiplies the dividends of diversity by letting each arrival deploy skills at full throttle from day one.

Counting the Cost of Delay

Procrastination already carries a measurable price tag. Government debt stands at ¥1.32 quadrillion, a record that pencils out to nearly ¥10 million per taxpayer. Each 0.1 percentage-point shortfall in productivity growth, compounded over a decade, adds roughly ¥15 trillion to that debt pile. Political optics may still tolerate incrementalism, but foreign observers are losing patience: even US President Joe Biden criticized "xenophobia" as a drag on Japan's growth, prompting a rare diplomatic complaint from Tokyo that ironically reinforced the underlying issue. Markets interpret such signals faster than ministries; a single downgrade in sovereign credit would raise servicing costs enough to erase the entire fiscal room now earmarked for fertility subsidies. Delay, in other words, taxes all other policy ambitions—from defense modernization to green transformation—long before it shows up in the census.

The Strategic Case for Managed Diversity

Diversity is not a sentimental plea for multiculturalism but a strategic asset that multiplies innovation. Convenience-store logistics during the 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake were kept intact by Vietnamese drivers and Nepalese depot managers whose multilingual coordination shaved hours off restocking cycles. A Yokohama-based gaming start-up that cracked the global top-ten chart this spring runs 40% of its codebase written by Indian engineers working remotely from Sapporo. These cases illustrate a broader trend: sectors that integrate foreign talent are punching above their macro weight. The reputational benefits are equally potent. In a region where economic heft equals diplomatic voice, Japan cannot afford to cede soft-power influence to competitors who field more internationalized workforces. A target of foreign labor at 7% of the workforce by 2035 is ambitious yet achievable and would return the dependency ratio to its 2015 level, buying priceless fiscal and geopolitical breathing space.

Conclusion: Turning the Archipelago into a Magnet

Japan retains unmatched assets—world-class public safety, high-speed connectivity, and deep capital markets—that could make it the ultimate magnet for global talent. But magnets require polarity. The current negative charge of closed hiring queues and opaque advancement must flip to a positive field of transparent meritocracy. Immigration, in that calculus, is not a concession but the catalyst that forces a long-overdue re-wiring of corporate metabolism. The choice is stark: evolve into a cosmopolitan hub that blends the precision of monozukuri with the ingenuity of global minds, or slip politely into elegant decline powered by ever-dimmer neon. History's verdict will not hinge on committee white papers but on whether Japan accepts that diversity, far from diluting identity, furnishes the only viable engine for its next economic miracle.

The original article was authored by Kumiko Nemoto, a Professor of Management at the School of Business Administration, Senshu University, Tokyo. The English version, titled "Japan needs diversity amid demographic decline," was published by East Asia Forum.

Reference

Aoki, M. (2024), "Labour productivity trends in Japan: Structural limits and digital investment gaps," Japan Productivity Center Research Bulletin, March.

Bloomberg News (2024), "Japan considers loosening immigration rules for skilled foreign workers," Bloomberg, 15 April.

Genda, Y. and Higuchi, Y. (2023), "Working-hour constraints and labor market outcomes in Japan," Japan Labor Review 20(2): 3–19.

Japan Productivity Center (2024), International Comparison of Labour Productivity 2024, Tokyo: JPC, December.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2025), Preliminary Vital Statistics for 2024, Tokyo: Government of Japan, March.

Ministry of Justice (2024), "Annual Statistics on Foreign Nationals," Immigration Services Agency of Japan, January.

Morikawa, M. (2023), "Productivity and work style reforms in Japan's service sector," RIETI Discussion Paper Series 23-E-004.

Nakata, Y. and Shinozaki, N. (2023), "HR reform in Japanese megabanks: Towards meritocracy?" Nikkei Asia, 10 November.

OECD (2023), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2023 Issue 2: Preliminary Version, Paris: OECD Publishing.

Park, D. and Shin, K. (2024), "Demographic headwinds and labor policy in East Asia," Asian Development Bank Working Paper Series No. 1340.

Statistics Bureau of Japan (2023), Labour Force Survey (Annual Average Results), Tokyo: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2022), World Population Prospects 2022, New York: United Nations.

World Bank (2024), "Net migration trends and dependency ratios in high-income Asia," World Development Indicators, April.