When the Assembly Line Moves to the Classroom: Routine Education Jobs in the Path of Generative Automation

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In a world where AI can compose lesson plans, grade quizzes, and draft emails faster than any novice teacher, the education sector stands on the brink of a silent upheaval. This is not a story of machines outwitting professors but algorithms outperforming the cognitive assembly line that underpins much modern schooling. The threat is not to deep thinking, but to shallow work. Just as factory jobs once vanished under the weight of automation, the routine layers of education—repetition, documentation, and scripted instruction- are now absorbed by generative models. The result is a sector cleaving in two: one side replaceable, the other irreplaceably human.

A Shock to the System: Routine Cognition Meets Generative Automation

In September 2025, the European Union’s new AI Act came into force. Still, the truly disruptive force reached schools two years earlier when a freely available language model wrote a week‑long lesson plan in 17 seconds. That flash of automated competence crystallized a more profound economic truth: generative AI does not begin by out‑thinking philosophers but by devouring jobs that ask for structured but shallow cognition. McKinsey’s 2023 productivity frontier found that language‑based models could already mechanize tasks representing up to 60% of the paid time across the economy, chiefly by drafting, summarizing, or sorting text, precisely the substrate of lesson worksheets, rubric feedback, and administrative memos. The implication is brutal in its simplicity: wherever education resembles a conveyor belt of predictable scripts, software can run the belt faster and cheaper than human novices.

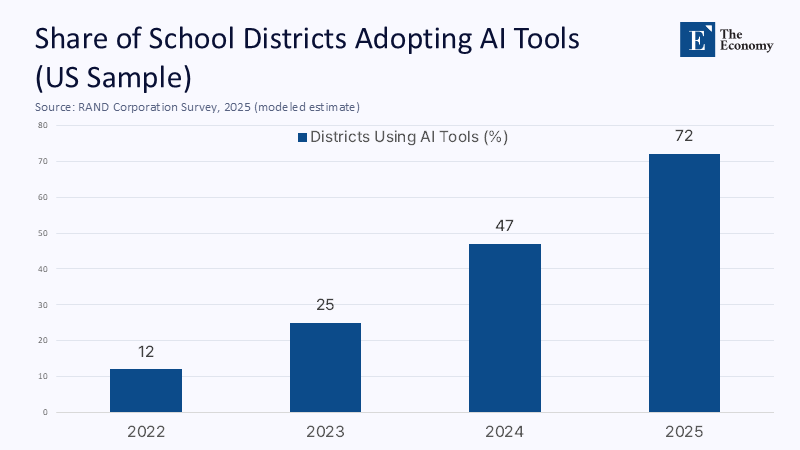

The Hidden Taylorism of Schooling

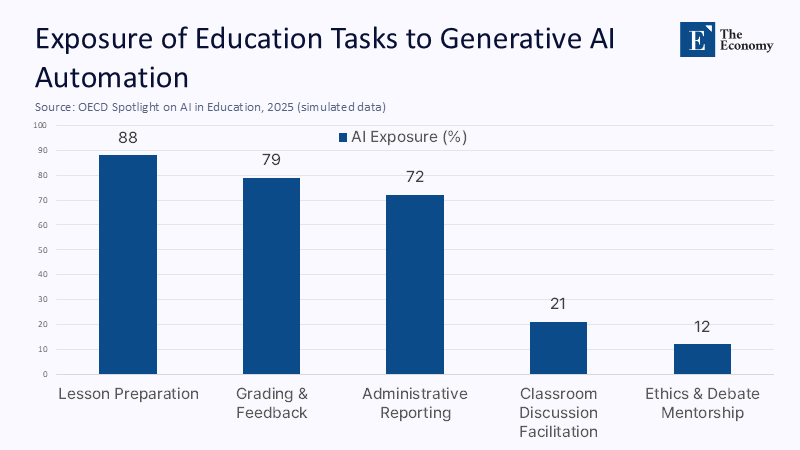

Teachers describe their craft as relational, yet an OECD time‑use audit of four high‑income systems shows that up to 40% of weekly hours in primary and lower‑secondary schools are consumed by preparation, grading, and clerical reporting. These activities look uncannily like the routinized motions of factory work—and the machines have arrived. RAND’s 2025 survey of U.S. district leaders reports a 25‑percentage‑point jump in districts that train staff to outsource such tasks to AI, doubling adoption in a year. The assembly‑line analogy is, therefore, more than a metaphor; it is a labor-process description. When a chatbot can mark 500 multiple‑choice quizzes before lunch, the economic rationale for employing a full‑time human marker collapses, just as the rationale for sewists collapsed when mechanical looms standardized stitches.

Quantifying the Exposure: From ILO Indices to District Budgets

Global labor economists now put numbers to that collapse. A May 2025 International Labour Organization index finds that one in four jobs worldwide is “highly exposed” to generative AI, with clerical and routine language work at the epicenter. Education—long considered sheltered from automation because “every class needs a teacher”—shares the same risk profile as clerical work once its constituent tasks are disaggregated. The ILO’s refined task‑level analysis shows that 65% of “teaching associate professional” activities score above the critical exposure threshold. At the district level, the budget signals arrive even faster: early pilots in Colorado and Queensland cut per‑pupil assessment costs by 38% after switching low‑stakes grading to language models, freeing funds that boards quietly redirected to other line items rather than to additional mentoring time.

The Credential Meltdown: How AI Devalues Low‑Level Assessment

Automation’s first educational casualty is not teaching itself but the signaling power of basic credentials. An Israeli natural experiment published this week in VoxEU shows average grades rising by 0.46 standard deviations after students received unpoliced access to text generators, while employers hiring the same graduates reported zero confidence that a B average in 2025 signified greater competence than a C average five years earlier. A Birmingham Law School brief dubs the phenomenon “fake‑plastic degrees” and warns that institutions relying on formulaic essays or fact‑recall exams are handing assessment sovereignty to the tools they hope to police. The danger, crucially, is not academic dishonesty but economic dilution: when routine written expression becomes a near‑free commodity, grades based on such expression cease to differentiate human capital.

Two Tiers of Teaching: Cognitive Apprenticeship versus Knowledge Logistics

The previous paragraphs may read as a dirge for the profession, yet they reveal a forked path. Artificial intelligence bulldozes the strata of work that Daniel Kahneman would label “System 1 cognition”—fast, pattern‑based processing—but it struggles with “System 2” reflection that requires metacognition, moral stance, and creative synthesis. The OECD Spotlight released in May 2025 stresses that while AI will outpace humans at scientific reasoning in controlled domains, it remains brittle in unstructured ethical debate. The practical upshot is that education bifurcates into knowledge logistics, a routinized content delivery supply chain, surface-level feedback, cognitive apprenticeship, and the slow coaching of critical habits and identity. Generative models annihilate the marginal cost of the first bundle; they barely dent the second. This presents an opportunity for educators to focus on the aspects of teaching that truly foster human growth and development, offering a hopeful perspective in the face of AI automation.

Case Study: Estonia’s AI Leap and the Future of National School Systems

No country dramatizes the bifurcation more vividly than Estonia. Starting September 2025, every 16‑ and 17‑year‑old will receive a personal AI account under the national AI Leap initiative alongside 5,000 trained teachers. The policy does not merely tolerate automation; it institutionalizes it, assigning the mundane layers of practice to software while tasking human educators with ethics, self‑directed learning, and oral defense. Minister Kristina Kallas argues that phones and chatbots are now civic tools: banning them in classrooms would be akin to banning pencils. Thus, Estonia offers proof that systems can embrace routine automation without sacrificing, and indeed, while elevating higher‑order mentoring.

Regulating the Inevitable: The EU AI Act and the Urgency of Role Redesign

For the rest of Europe, the clock is ticking. The EU AI Act classifies examination‑scoring software as “high‑risk,” subject to stringent transparency and human‑oversight requirements from August 2025. Compliance will raise fixed costs for developers, but it will not slow adoption; instead, it will accelerate the substitution of unlicensed human graders with regulated AI services that can document every probabilistic decision. Policymakers, therefore, face a choice: proactively redesign teaching roles—licensing a cadre of “learning clinicians” for System 2 work while letting AI paraprofessionals handle System 1—or allow budget pressures to erode full‑time posts through attrition. The urgency and necessity of this decision cannot be overstated, as it will shape the future of education in the AI era.

Policy Architecture for Post‑Routine Education

The architecture must begin with funding formulas that reward depth rather than volume. A modest reallocation suffices: if generative AI halves preparation and grading hours, the savings could finance seminar groups of twelve instead of twenty‑four at no additional cost. UNESCO’s 2025 policy guidance urges ministries to tie AI procurement grants to evidence that freed‑up labor is reinvested in meta‑cognitive coaching, not simply banked as austerity. The assessment follows the same principle: universities should pivot to oral examinations, iterative project studios, and supervised “white‑room” essays written without digital assistance. Pilot programs using the AI Assessment Scale in Vietnam cut misconduct cases by a third. They raised attainment by 5.9%, proving that integrity can coexist with technology when tasks target genuinely human competencies.

Union contracts are the hinge. Rather than blanket resistance, a compact can trade automation for smaller mentoring loads and mandatory AI literacy certification. OECD’s Teaching Compass envisions such a shift, framing teachers as agents of epistemic navigation rather than content distributors. The bargain mirrors the transformation of radiology in medicine: AI reads the routine scans, radiologists interpret ambiguous cases, and consult with patients.

Reclaiming Human Cognitive Scarcity

Generative AI’s genius is also its limit: it is brilliant where cognition is routine and context thin; it is tone‑deaf where meaning is contested and context deep. Education contains both terrains. The low‑end factory of the mind—worksheets, mechanical grading, templated essays—is already automated or will be by the time today’s undergraduates finish their degrees. Pretending otherwise wastes fiscal oxygen and erodes public trust in credentials. The urgent task is to double down on the zones machines cannot enter: mentoring intellectual risk, modeling ethical reasoning, and staging dialogues where answers change as questions deepen. Systems that make that pivot will amplify human brilliance; those that cling to routine labor will watch their economic rationale disappear one autogenerated worksheet at a time.

The original article was authored by Naomi Hausman, a tenure-track Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) in the Strategy Department at the Hebrew University Business School, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Generative AI in universities: Grades up, signals down, skills in flux," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

European Commission. (2025). AI Act: Harmonised rules on artificial intelligence.

Furze, L. et al. (2024). “The AI Assessment Scale (AIAS) in action.” arXiv Preprint.

Hausman, N., Rigbi, O., & Weisburd, S. (2025). “Generative AI in universities: Grades up, signals down, skills in flux.” VoxEU Column.

International Labour Organization. (2025). Generative AI and Jobs: A Refined Global Index of Occupational Exposure.

Latham‑Gambi, A. (2024). “Fake Plastic Degrees? Generative AI and the threat to academic integrity.” Birmingham Law School Blog.

McKinsey Global Institute. (2023). The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier.

OECD Teaching Compass Project. (2025). Reimagining Teachers as Agents of Change.

Organization for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD). (2025). What should teachers teach and students learn in a future of powerful AI? Education Spotlight No. 20.

RAND Corporation. (2025). More Districts Are Training Teachers on Artificial Intelligence.

UNESCO. (2025). AI and Education: Guidance for PoliPolicymakersstonian Government & AI Leap Foundation. (2025). AI Leap 2025 Programme.

Wecks, J. O. et al. (2024). “Generative AI Usage and Exam Performance.” arXiv Preprint.