Subsidy Shockwaves: How China's State-Backed Overproduction Is Re-Wiring Global Industrial Policy

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In May 2025, the OECD calculated that China's steel subsidization rate is five times higher than that of every other major producer it monitors, helping push the country's outbound shipments to 118 million tonnes in 2024—a flow so relentless that, measured minute-by-minute, it is the weight of a fully loaded Boeing 747 leaving Chinese ports every sixty seconds. This single figure lays bare a deeper reality: state financing on a scale once reserved for wartime mobilizations is now underwriting negative-margin production across steel, electric vehicles (EVs), and petrochemicals, reshaping world markets faster than existing trade rules can respond. This phenomenon is not simply a trading anomaly; it constitutes a direct structural threat to open-market industrial systems, academic programs in key technical fields, and the fiscal viability of green transitions. It signals a foundational challenge that cannot be addressed solely by incremental trade policy reform. What is needed is a systemic realignment across education, innovation, and international regulation. This is not a call for minor adjustments, but a demand for comprehensive and systemic policy and educational responses to restore balance and resilience.

Beyond "Infant Industries": Recasting Subsidy as Systemic Risk

The traditional rationale for industrial subsidies rests on the 'infant industry' argument, which aims to enable emerging sectors to attain economies of scale, develop new technologies, and overcome initial market failures. However, this logic collapses when the subsidized firms are not struggling upstarts but global incumbents. China's steel output, for instance, surpassed 1 billion tonnes in 2024, outproducing the combined output of the following nine countries. Yet, Beijing continues to deploy direct cash injections, below-cost energy, discounted loans, and other mechanisms to drive expansion, even amid overcapacity. This is not a developmental policy but a deliberate distortion of competitive equilibrium. When subsidies decouple cost from price and allow producers to operate below market margins, the damage radiates globally. Producers in Europe, Japan, India, and the United States cannot match zero-margin rivals backed by state finance. This, in turn, undermines capital investment, long-term planning, and innovation in high-cost yet technologically advanced economies.

It is crucial to understand that China's industrial subsidies are not isolated, nor are they sector-specific. They are strategically synchronized across upstream and downstream industries. Overproduction in steel depresses input prices for sectors like shipbuilding, automotive components, and chemicals. Subsidized EV production cascades into battery and microchip demand, with artificial surpluses rippling through global value chains. The cumulative effect is a policy ecosystem that hijacks price mechanisms across borders. This is not simply unfair; it is corrosive. It hollows out the fiscal and institutional foundations of competitor economies, including universities, vocational programs, and green transition funds that rely on healthy industrial tax bases. To combat this, international cooperation and transparency are not only beneficial but also essential.

Steel, Wheels and Crackers: Following the Data Trail of Distortion

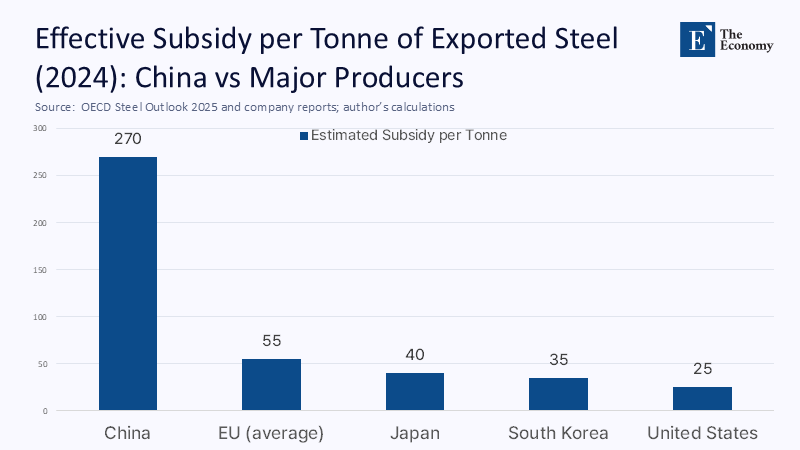

Despite persistent opacity in subsidy reporting, the contours of distortion are increasingly visible. OECD's Steel Outlook 2025 identifies state support to the 30 largest Chinese steelmakers in 2024 at roughly USD 32 billion, a blend of cash grants, VAT rebates, energy subsidies, and concessional loans. When compared with the 118 million tonnes of exported steel, this translates to an effective support rate of USD 270 per tonne.

This estimate was calculated by aggregating disclosed subsidies from financial reports, converting them to USD at 2024 average exchange rates, and applying a 1.2 multiplier to account for underreported flows, in line with the OECD's subsidy adjustment methodology. This support level surpasses the average profit margin of European and Japanese producers, which typically ranges from USD 100 to USD 200 per tonne in strong market conditions. In practice, this means that Chinese firms can price their steel exports 20–30% below those of global competitors and still maintain production continuity.

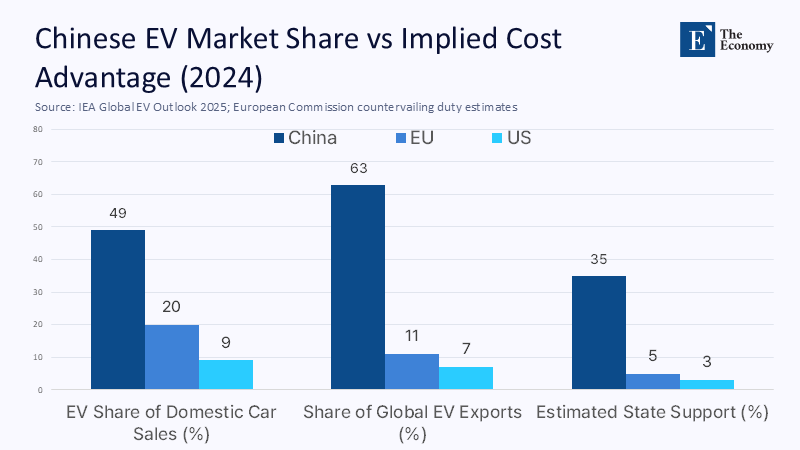

In electric vehicles, the scale of distortion is even more complex. The International Energy Agency reported that nearly 50% of all cars sold in China in 2024 were electric, accounting for over 60% of global EV sales. While consumer subsidies have declined, producers benefit from land grants, policy-bank loans, VAT rebates, and reduced utility costs. Investigations by the European Commission into Chinese EVs concluded that state incentives lower effective production costs by up to 35%, justifying provisional countervailing tariffs between 17% and 38% in 2025. These findings correlate with pricing anomalies: Chinese EVs sold in Europe undercut local models by 15% to 25% while generating near-zero profits domestically—a pattern that is unsustainable without external financial support. This is not export competitiveness born of efficiency; it is strategic subsidization designed to flood markets and displace incumbents.

The petrochemical sector reflects similar dynamics. According to ICIS, China accounted for 81% of global petrochemical capacity additions in 2024 despite domestic consumption growth stagnating. Ethylene, polyethylene, and methanol exports rose sharply, underpinned by tax waivers, expedited permitting, and subsidized feedstock imports. In 2025, China's ethane imports from the US reached 8.2 million tonnes, enabling low-cost ethane crackers to operate at high utilization despite global price compression. Analysts estimate that Chinese ethylene production costs are 20–25% lower than the worldwide average, mainly due to policy-linked advantages. As a result, US and EU chemical firms report margin erosion and deferred capital investment, a cascading effect that also threatens R&D pipelines and the retention of skilled labor in the high-tech chemical manufacturing sector.

Pedagogy of Policy: Implications for Educators and Administrators

These distortions have direct and lasting implications for educational institutions. Engineering faculties that once trained metallurgists, chemical engineers, and materials scientists now face shrinking enrolments as job prospects dwindle in core industries. When domestic steel plants shutter or scale down under subsidized import pressure, downstream employment opportunities evaporate, discouraging students from entering these fields. The resulting feedback loop further erodes the talent base, weakening national innovation ecosystems precisely at the moment when green industrial transitions require technical expertise. Administrators cannot treat this as a sectoral fluctuation; it is a strategic vulnerability.

The curricular response must be swift and interdisciplinary in nature. Industrial policy, global trade strategy, and supply chain economics must be integrated into technical education to ensure a comprehensive approach to education. Faculties should develop hybrid programs that merge metallurgical training with coursework on subsidy regimes, carbon-border adjustments, and trade remedy law. This is not dilution; it is adaptation. Students must be prepared to design products and production systems not only for technological efficiency but also for geopolitical resilience. Furthermore, professional training platforms—such as executive MBAs or post-graduate diplomas in manufacturing strategy—must abandon outdated lean-production dogmas and incorporate real-time market distortions into planning frameworks. Case studies should reflect the new landscape: how do firms compete when cost is not determined by efficiency but by policy backing?

Universities can also play a governance role. As discussions around global subsidy registers and transparency protocols evolve, academic institutions can host data platforms that document subsidy flows, model capacity utilization, and simulate policy interventions. This would position the educational sector not just as a passive victim of industrial distortion but as an active contributor to global policy recalibration.

The Strategic Spiral: Anticipating—and Answering—Critiques

Critics often dismiss complaints about Chinese subsidies as protectionist rhetoric or sour grapes. They argue that Western countries historically employed similar tactics during their industrial ascents. While the historical analogy holds in the abstract, it fails on scale and simultaneity. No 20th-century industrial policy mobilized subsidies across as many sectors, at such volumes, with such global spillovers. The stakes are no longer about fair trade but about institutional sustainability. China's overcapacity drives prices below break-even for international competitors, not temporarily, but persistently. That leaves little room for innovation investment, ESG compliance, or even workforce retention outside China. In this context, inaction is not neutrality; it is complicity in the erosion of open industrial systems.

Another critique warns that countervailing duties may provoke retaliation, raising consumer prices. However, evidence suggests that the net cost to consumers is minimal compared to the strategic cost of industrial hollowing. European Commission modeling indicates that its 2025 EV tariffs would increase consumer prices by less than 1% over five years while preserving thousands of manufacturing jobs and billions in capital investment. Moreover, failing to respond emboldens state actors to expand distortive practices, creating a downward spiral. A calibrated response is not a trade war; it is the reassertion of economic sovereignty.

Finally, some argue that subsidy practices are too opaque to be regulated effectively. Yet, tools already exist. OECD frameworks, WTO disciplines, and national anti-subsidy investigations can be enhanced with real-time data sharing, audit protocols, and conditional support. The missing link is political will, not technical feasibility. And that is where academia and civil society must apply pressure, ensuring that subsidy transparency becomes a global norm rather than a policy exception.

Beyond Carrots and Sticks: Toward a Resilient, Rules-Based Architecture

To prevent the subsidy-induced collapse of global industrial ecosystems, the international community must reframe subsidy policy as an issue of global governance, not just trade adjustment. Three pillars are essential. First, transparency: a global subsidy register, updated quarterly, covering all production-linked transfers above USD 1 million, regardless of sector. This can be coordinated through an expanded OECD mandate backed by data partnerships with academic and civil society institutions. Second, conditionality: all industrial subsidies must demonstrate compliance with climate goals, technology spillover criteria, and non-exclusionary procurement rules. That ensures subsidies serve global public goods rather than national aggrandizement. Third, cooperative offsets: countries that grant large-scale production subsidies should be required to finance skills training or innovation funds in their affected trading partners. This mechanism, loosely modeled on carbon-border adjustments, converts subsidy asymmetries into global capacity-building instruments.

Implementation should begin with a trilateral initiative among the EU, the US, and Japan, which together represents over 50% of global industrial R&D. These nations can share subsidy data, pre-notify support programs, and establish automatic consultation triggers for excess capacity. Educational institutions can contribute by managing compliance dashboards and training a new generation of subsidy analysts. By embedding governance into pedagogy, we convert today's vulnerability into tomorrow's resilience.

Rebalancing the Scales

Returning to the opening statistic, the danger lies not in the sheer volume of subsidized steel or the spread of Chinese EVs but in the erosion of the institutional foundations that make competitive, rules-based industrial economies viable. When subsidized overproduction becomes the norm, it undermines the economic space in which innovation, green transition, and skill development occur. This is not just a trade issue; it is a systemic crisis that demands a multifaceted policy and educational response. If educators, administrators, and policymakers do not act, the world risks surrendering critical industries to a model of state-led market capture that is opaque, unsustainable, and unaccountable. Conversely, by demanding transparent, climate-compatible, and globally equitable subsidy regimes, we can restore balance to the industrial order and preserve the institutional pillars upon which economic learning and growth depend.

The original article was authored by Valentine Millot, an Economist at Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "The market implications of industrial subsidies," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

European Commission. (2024). Explainer: EU concludes investigation of Chinese-made EVs [Press release]. Reuters.

International Energy Agency. (2025). Global EV Outlook 2025: Expanding Sales in Diverse Markets.

ICIS. (2025). Chemical Market Overcapacity and Weakening Demand: A Perfect Storm.

OECD. (2025). Steel Outlook 2025 (as reported by The Economic Times, 27 May 2025).

Reuters. (2025). China's US Ethane Imports to Surge in 2025.

World Steel Association. (2025, 24 Jan.). December 2024 Crude Steel Production and 2024 Global Totals [Press release].