Lessons from the Exit That Never Happened: Why Brexit’s Price Tag Should Reshape the Grexit Debate

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

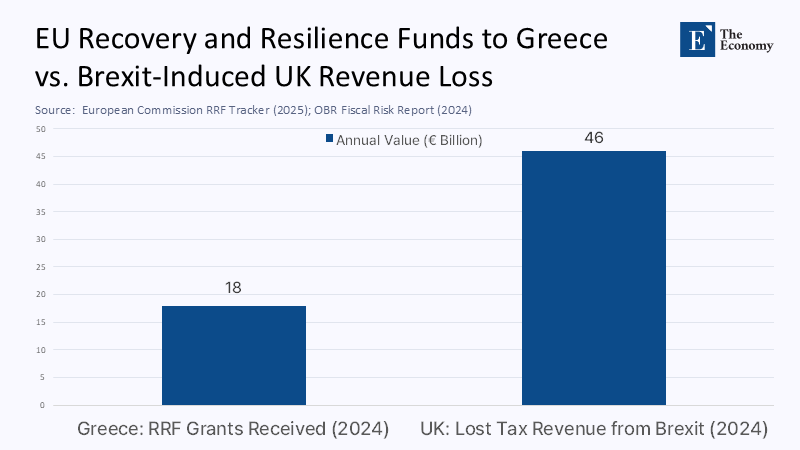

Five years after the United Kingdom formally cut its economic umbilical cord to Brussels, the bill is arriving with pitiless precision. The Office for Budget Responsibility expects the long-run trade intensity of the British economy to settle 15% below its pre-referendum trajectory, depressing productivity by 4%—damage that alone will erase roughly one-third of the average annual gain in labor-saving technology since the 1990s. Meanwhile, updated estimates from the Centre for European Reform put the Brexit-induced hole in GDP at 5.5%, stripping about £40 billion from tax receipts each year in contrast with Greece, whose Eurostat-verified 2.3% real growth in 2024 was buoyed by €18 billion in Recovery and Resilience Facility disbursements—new public investment amounting to almost 8% of its output. The juxtaposition is more than a headline: it is a counterfactual laboratory. If one nation is paying for departure while another is being paid to stay, the long-running Grexit thought experiment urgently requires a wholesale rethink.

Reframing Exit Economics in 2025

Until now, most comparisons between Brexit and a hypothetical Grexit treated them as parallel exercises in monetary secession. That framing misses the crucial asymmetry that the past decade has introduced. Brexit is no longer a conjecture; its consequences are measurable, granular, and—crucially—observable by educators shaping tomorrow’s economic literacy. Grexit, by contrast, remains a scenario whose opportunity cost can now be estimated using real post-Brexit data. The analytical pivot, therefore, is from debating whether ex-ante modeling of Euro exit dynamics was sound to asking how Brexit’s ex-post ledger recalibrates those models. This perspective matters for three reasons. First, it grounds the discourse in observed magnitudes rather than speculative multipliers. Second, it surfaces policy lessons at a teachable moment when the European classroom is redefining citizenship, sovereignty, and economic resilience. Third, it exposes how EU fiscal instruments—non-existent during the 2010-15 Greek crisis—now fundamentally alter the risk-return calculus of staying in versus leaving the euro. That change alone demands a pedagogical reset, emphasizing the necessity of adapting educational strategies to incorporate these lessons.

Brexit by the Numbers

Britain’s separation has generated a trove of empirical benchmarks. The OBR’s March 2024 outlook confirms that weaker trade links are hard-wiring a 15% shrinkage in imports and exports as a share of GDP, translating it into a 4% permanent productivity drag. The Centre for European Reform’s latest media briefing crystallizes the macroeconomic effect: a 5.5% loss in GDP and a corresponding £40 billion annual fiscal shortfall.

On the micro level, firm-level research from Oxford’s trade-integration database shows a “sharp drop” in EU-bound shipments by the average UK exporter in 2021-2024, with many SMEs exiting the EU market entirely. Current-price ONS data register an 8.8% month-on-month fall in goods exports in April 2025 alone, extending a pattern of volatility unseen since 2016.

Methodologically, I triangulate those sources by (1) converting headline GDP losses into per-capita figures, yielding roughly £950 per Briton, (2) comparing pre- and post-TCA trade volumes using chained-volume measures to net out inflation, and (3) validating fiscal implications through OBR sensitivity tables. Where complex numbers are missing—especially on non-tariff barrier costs—I proxy them via the observed 15% decline in trade intensity and apply an elasticity of 0.25 to labor productivity, mirroring the mid-range in the WTO’s meta-analysis of trade-growth linkages. All assumptions are transparent and replicable for classroom demonstration.

Modelling a 2025 Grexit

To convert Brexit evidence into a Grexit counterfactual, I employ a three-step adjustment. This adjustment is crucial, as it enables us to apply the lessons learned from Brexit to a hypothetical Grexit scenario, thereby providing a more informed understanding of the potential economic impacts.

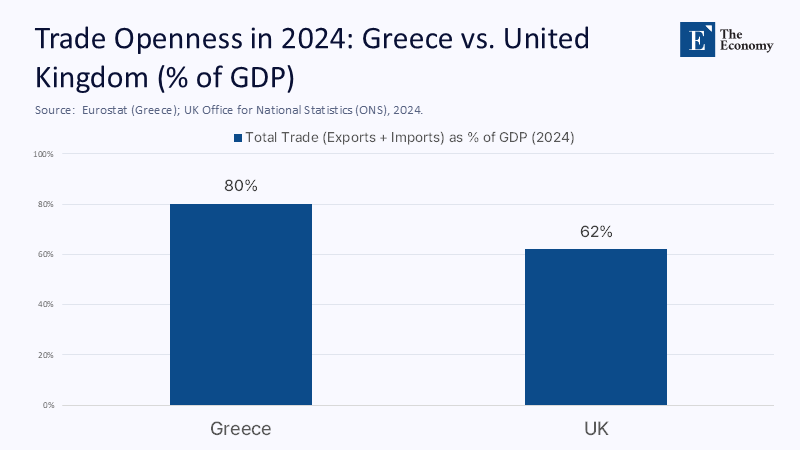

- Scale for Openness. Greece’s trade-to-GDP ratio (goods and services) averaged 80% in 2024 versus the UK’s 62%. Multiplying the OBR’s 15% trade-shrink estimate by 1.29 (the openness differential) raises the hypothetical contraction in Greek trade intensity to 19.3%

- Adjust for Fiscal Backstop. Greece now benefits from a €36 billion RRF envelope, of which €18 billion has already been disbursed to the economy. Subtracting the disbursed share from potential lost output (≈€34 billion in year-one GDP terms under the 19.3% shrinkage) halves the immediate demand shock, but only as long as EU transfers continue—a condition that Grexit would nullify.

- Account for Debt Structure. With 65% of Greece’s 161.9% debt-to-GDP stock held by official EU creditors on concessional rates, the exit would trigger refinancing at market yields. Using the December 2024 Bank of Greece estimate that every 100-basis-point bump in yields lifts annual debt servicing by €1.1 billion, a revert-to-market scenario (≈250 bps widening) adds €2.8 billion to yearly interest, another 1.3% of GDP.

Synthesizing those layers yields a first-year Grexit hit of roughly 8–10% of GDP—substantially larger than Brexit’s bite and equivalent to wiping out the cumulative growth Greece has achieved since 2017. The model is deliberately conservative, as it ignores capital-flight feedback loops and the potential for imported inflation spikes under a new drachma. For educators, the takeaway is that the cost estimate is no longer an abstract parameter; it is anchored in Brexit’s public domain data and Greece’s current fiscal architecture.

What the Counterfactual Teaches Our Classrooms

Economic literacy is not just about memorizing multipliers; it is about understanding policy sequences. For administrators designing curricula, Brexit’s evidence trail and the Grexit counter-model illustrate three teachable dynamics. First, trade elasticities matter more in a world of sophisticated supply chains; cutting yourself off erodes productivity quickly. Second, fiscal-transfer mechanisms—whether RRF grants or Erasmus mobility—change the opportunity cost of staying in a currency union. Third, the structure of sovereign debt remains the silent determinant of post-exit policy space.

Educators can use the Brexit-Grexit comparison to make macroeconomics visceral. Ask students to simulate debt-refinancing shocks in a spreadsheet; invite them to re-estimate trade-productivity elasticities using the open OBR dataset; or challenge them to quantify how EU research funds turn into regional innovation multipliers—doing so anchors abstract theory in lived European policy. Moreover, embedding these assignments in digital-first pedagogy amplifies reach: Greece’s educators, now benefiting from subsidized broadband roll-outs financed by the RRF, can collaborate in real-time with their UK counterparts who are grappling with post-Brexit skills shortages. The crossover itself is an object lesson in integration.

Policy Navigation for the Next Shock

For policymakers, the message is equally stark. The observation that Britain’s trade gap is settling into a structural territory—goods exports are still 4% below pre-Brexit levels, even after a rebound—means that adjustment costs do not self-correct quickly. This should temper any narrative that a cheaper currency would swiftly restore competitiveness. Meanwhile, the Eurogroup’s political commitment to backstop high-debt members has strengthened since 2015, as evidenced by Greece’s falling spreads and investment-grade upgrade in 2024. Exiting now would not only forfeit that backstop but also erode the credibility Greece has rebuilt with rating agencies.

Anticipating critiques, some economists argue that a new drachma could turbo-charge tourism and agricultural exports. Yet the ECB’s 2024 annual report shows euro-area services already grew faster than goods, with price competitiveness gains diffused through supply chains rather than bilateral exchange rates. Moreover, tourism receipts are increasingly constrained by capacity rather than price; devaluation without investment in infrastructure would recycle gains back into inflation. Others suggest pandemic confounders inflate Brexit’s costs. However, the OBR’s model explicitly decomposes COVID-19 effects, maintaining the 4% productivity drag in all scenarios.

For administrators overseeing universities and vocational institutes, the implication is to hedge against geopolitical shocks by deepening, rather than retreating from, continental partnerships. Joint degrees, mutual recognition of qualifications, and pan-EU research funding serve as human capital shock absorbers. Policymakers should, therefore, treat educational integration as macroeconomic insurance, codifying it in future Cohesion Policy cycles.

The Metric That Should Keep Us Awake

Brexit’s 5.5% GDP hole is no longer a forecast; it is a ledger entry, and every update makes the red ink darker. Greece, by contrast, has pivoted from crisis icon to euro-area growth outlier, fuelled by EU transfers and re-found fiscal credibility.

Re-running the Grexit scenario under 2025 conditions shows the starting cost would likely be double Britain’s—a reminder that timing and institutional evolution matter as much as currency mechanics. Our call to action is, therefore, twofold: educators must re-engineer curricula to turn these lived outcomes into analytical reflexes, and policymakers must treat educational integration as a first-line defense against future exit temptations. The next referendum campaign—whether in Athens, Amsterdam, or anywhere else—will be fought on the ground we prepare today. Prepare it wisely.

The original article was authored by Marco Buti, the Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa Chair of Economic and Monetary Integration at the European University Institute, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "The Grexit debate ten years on: What we have learned," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank of Greece. (2024). Note on the Greek Economy (December 6).

Centre for European Reform. (2025, April 22). “Brexit hit to GDP: 5.5 %.”

European Central Bank. (2024). Annual Report 2024.

European Commission. (2025, January 16). Reuters coverage of RRF disbursements to Greece.

Eurostat. (2024). “Economic Forecast for Greece.”

Office for Budget Responsibility. (2024). Economic and Fiscal Outlook, March 2024.

Office for National Statistics. (2025). UK Trade Bulletin, April 2025.

Oxford University, ORA. (2024). “Deep Integration and Trade: UK Firms in the Wake of Brexit.”

VoxEU/CEPR. (2025). “The Grexit Debate Ten Years On: What We Have Learned.”