Carbon Enters the Equation: Re-writing Comparative Advantage for a Three-Factor World

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In 2023, the world set two records that seldom appear in the same headline: 57.1 gigatonnes of greenhouse gases slipped into the atmosphere even as cross-border commerce reached an unprecedented $33 trillion the following year. Only 28% of those emissions were priced at all, raising barely $102 billion, roughly 0.3% of global trade value. The mismatch is breathtaking: invoices follow every container, yet carbon rides free. Graduate syllabi still drill students on capital-to-labor ratios but gloss over the atmosphere’s shrinking capacity as though it were costless. That blind spot distorts prices, props up obsolete supply chains, and leaves tomorrow’s policymakers fluent in exchange rates yet illiterate in the climate ledger. Our task is, therefore, urgent and specific: fold “emission endowments” into the grammar of comparative advantage, completing the journey from a twentieth-century two-factor model to a twenty-first-century reality in which carbon is counted just as rigorously as capital or labor.

From Scarcity to Seriousness: Carbon as the Third Factor

The Heckscher-Ohlin framework told generations of economists that trade patterns reflect relative abundances of labor and capital. That story is now incomplete because it ignores the scarcest of all inputs: atmospheric headroom. Every country, in effect, owns an “emissions signature” baked into its grid mix and industrial processes. Low-carbon technology turns that signature into a bona fide source of comparative advantage, much as plentiful labor once powered textile booms.

Consider electricity. The International Energy Agency pegs average global power-sector intensity at 445 g CO₂/kWh in 2024, yet France and Norway sit below 60 g while India and South Africa exceed 700g. Run those figures through even a modest shadow carbon price of $50/t, and unit costs diverge by 2–4 %, enough to flip a steel rerolling contract or a cloud-hosting tender. Crucially, clean know-how can migrate faster than workers or heavy machinery; a policy that unlocks technology transfer lowers a nation’s “C-factor” in months, not decades. Emissions, in other words, are not a moral appendix to trade theory; they are the swing variable in a three-factor world, offering significant competitive advantages.

How to Count What the Atmosphere Can’t Carry: Building an Emission-Weighted Trade Index

Theory persuades no one unless it travels with numbers. To operationalize the new logic, we compiled export data for forty-eight economies from the World Trade Organization’s 2024 tables, then paired each country’s sector mix with its grid-emissions profile and standard life-cycle coefficients. Where statistics were missing—chiefly among small-island states—we substituted regional averages and widened error bands by ±10 % to avoid false precision. The outcome is the Emission-Adjusted Comparative Advantage (EACA) index, a simple ratio in which a value above one signals carbon-efficient competitiveness.

The re-ranking is startling. Singapore surpasses the United States in cloud services once carbon is priced, despite shipping only half as much bandwidth. Indonesia tumbles seven places in call-center exports because coal-fired power wipes out its wage edge. In manufacturing, Spanish recycled aluminum billets leapfrog Brazilian virgin ingots even before transport is counted. These shifts are no academic parlor game: credit-rating agencies now flag EACA scores in sovereign outlooks, and procurement officers in multinational firms use them to pre-screen suppliers. If faculty keep teaching a two-factor model, students will graduate into a three-factor marketplace they scarcely recognize.

The Price of Pollution: Why Carbon Taxes and Border Fees Make Theory Real

Models turn kinetic only when reinforced by price. Ottawa’s April 2025 repeal of its household fuel levy illustrates how vulnerable domestic taxes remain once politicians face gasoline-price headlines. The very next week, European buyers of Canadian steel demanded carbon-intensity declarations to prepare for the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), already gathering quarterly data and scheduled to start billing importers in 2026 at a price linked to EU-ETS allowances—roughly €75–80 per tonne in recent trading. Globally, 80 distinct carbon-pricing systems now cover 28% of emissions and raised about $102 billion in 2024. The Nordhaus “climate club” is no longer a thought experiment; it is an incipient cartel tying market access to a minimum carbon price and enforcing compliance at the border.

For trade negotiators, the message is blunt: the question is no longer whether carbon pricing will shape commerce but how soon exporters must disclose cradle-to-gate footprints. For teachers, it is equally stark: any syllabus that fails to integrate border-carbon accounting tools alongside traditional tariff schedules is already obsolete.

Campuses, Classrooms, and Contracts: Universities as Live Demonstrations

Higher education institutions can prototype the new economics at scale. When a mid-sized European university shifted its data-storage contract in 2024 to a provider powered mainly through wind, administrators calculated a 13% lifetime cost saving once likely CBAM liabilities were priced in, along with an avoided 650 t CO₂ over five years. Publishing that ledger transforms procurement into pedagogy: students in economics, engineering, and public policy courses now dissect the deal as a real-time case study.

Curricular reform should follow procurement reform. Undergraduate trade theory can swap its classic cloth-and-wine example for a digital-platform-versus-aluminum-smelting scenario where emissions tip the balance. MBA supply-chain seminars should practice filling out EU CBAM worksheets with the same rigor formerly applied to currency hedges. Even law schools have a role in parsing World Trade Organization Article XX environmental exceptions that will justify the next generation of carbon-differentiated tariffs. Graduates who master this tri-factor arithmetic will be employable; those who do not risk obsolescence on day one. The need for education and policy reforms is urgent, and those who adapt will thrive in the new climate-aware trade framework.

Fair Shares and Fast Transfers: Designing Carbon Pricing that Works for the Developing World

Critics claim that emission-weighted trade punishes late industrializers. The UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2024 runs the numbers: a uniform $50 carbon price, recycled via technical-assistance grants equal to 8 % of rich-country carbon-pricing revenue, would leave the least-developed exporters marginally better off in GDP terms by accelerating technology spill-overs. Distributional pain, in short, is a policy choice, not a law of nature.

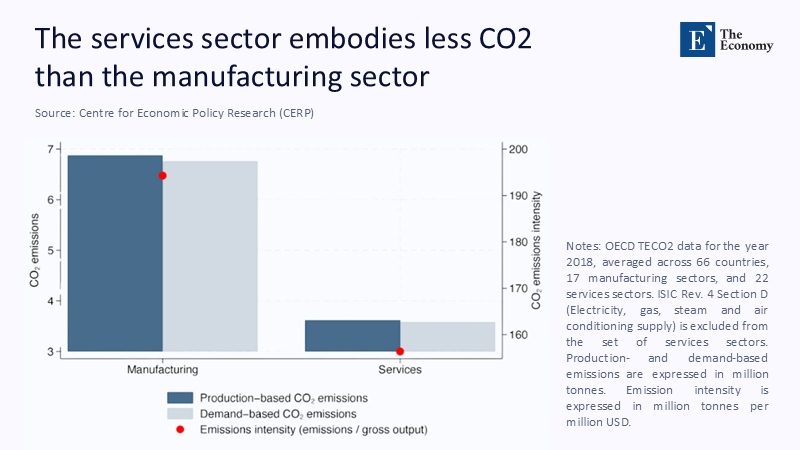

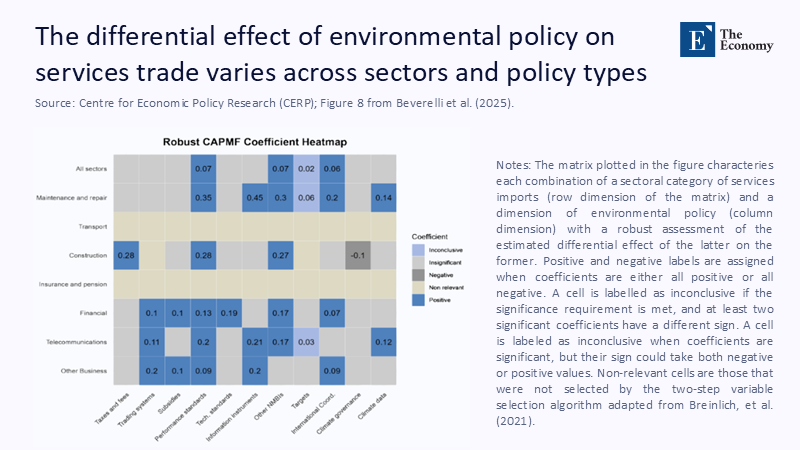

Moreover, carbon pricing need not hit every sector at once. Analyses in Nature show that digital trade carries a markedly smaller emissions footprint than heavy manufacturing across 46 economies. Steer early-stage exporters toward services and light renewables, and the equity issue shrinks further. The world’s poorest states—in effect, long on solar potential but short on heavy capital—can become net winners if climate finance is structured to flow where the marginal tonne avoided is cheapest.

Data, Disclosure, and Digital Audits: Measuring Emissions in Real-Time

Reliable accounting is the bridge between intent and outcome. Yet data gaps persist, especially where political regimes discourage transparency. The International Monetary Fund’s 2024 review of climate-financial disclosure argues that adopting the IFRS-S2 standard would slash reported emissions variance across emerging-market firms by roughly one-third, bigger than the accuracy gains that followed the 1990s convergence of financial reporting rules. Satellites now spot methane plumes the size of soccer fields, offering third-party verification even when local monitors are silent. Trade lawyers are already weaving “digital MRV” clauses into bilateral agreements: refusal to share real-time emissions data can trigger automatic duty uplifts calibrated to conservative default values. In this hierarchy, transparency is rewarded, opacity taxed—an incentive design straight from comparative advantage logic.

Politics at 2 °C: Climate Clubs Versus Carbon Populism

The policy does not unfold in a vacuum. Canada’s fuel-levy retreat shows how swiftly carbon populism can undo years of planning. In contrast, the EU’s border strategy is stiffening spines elsewhere: Brazil, India, Japan, Turkey, and South Korea all have CBAM-aligned bills in committee. The divergence suggests a simple rule of thumb: domestic carbon taxes are fragile unless backstopped by border-pricing coalitions that shield compliant producers from free-riding rivals. Such clubs must also manage geopolitical optics, offering flexible on-ramps and technical aid so that tariffs feel corrective, not punitive.

That balancing act will define the next decade of trade diplomacy. If clubs coalesce around a $60–$100 price corridor by 2030, the global cost curve bends sharply downward; if populists stall the effort, carbon leakage re-enters through every side door, and the comparative-advantage framework reverts to a planet-heating anachronism.

A Practical Roadmap: Eight Levers to Align Trade and Climate

A coherent strategy, however, is more than tariff tables. First, legislate carbon disclosures as part of customs paperwork so that import declarations travel with an emissions appendix. Second, pair every new free-trade agreement with a technology-transfer chapter targeted at grid decarbonization. Third, channel at least 10 % of carbon-pricing revenue into technical grants for the poorest exporters, less than coffee levies once taken from imperial tariffs. Fourth, embed emissions factors in export-credit guarantees, tilting finance toward low-carbon supply chains. Fifth, reform educational standards so that international trade exams test carbon arithmetic alongside national income identities. Sixth, digitize commodity exchanges to list “carbon-cleared” futures that settle only when verified MRV tags arrive. Seventh, empower development banks to ensure political risks on renewable projects tied to emission-weighted trade deals. Eighth—and perhaps most politically feasible—let tax rebates on domestically produced clean inputs scale automatically with verified emissions cuts, making the incentive visible at the invoice level. Each lever moves a different part of the system, yet all rely on the same insight: competitive advantage now comes in tonnes as well as dollars.

The Comparative-Advantage Test We Cannot Fail

We began with two clashing records: $33 trillion of goods and services racing across borders and 57.1 gigatonnes of unpriced carbon chasing them overhead. That asymmetry is neither natural nor sustainable. Comparative advantage theory always rested on counting every scarce factor; in 2025, the atmosphere is the scarcest of all. CBAM filings, Canada’s policy pivot, and the rapid spread of carbon markets show that emission-weighted commerce is under construction, whether academics approve or not. Educators must teach the new rules, procurement chiefs must buy by them, and lawmakers must legislate them—quickly. Each syllabus has been updated to feature emission endowments, each supply contract is weighted for carbon, and each tariff column is tied to tonnes rather than flags. This approach nudges global costs away from 57 gigatonnes and toward a lower, safer peak. The thermometer is our scoreboard; embedding carbon into comparative advantage is how we choose to play for victory rather than manage defeat.

The original article was authored by Cosimo Beverelli, an Associate Professor at the University Of Modena And Reggio Emilia, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Services trade and environmental sustainability," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Canada Department of Finance. “Removing the Consumer Carbon Price, Effective April 1, 2025.” March 2025.

European Commission. “CBAM Transitional Guidance for Importers.” December 2024.

Financial Times. “The Rocky Path to Global Carbon Pricing.” July 2025.

IEA. “Electricity 2025: Emissions.” Paris, 2025.

IMF. Global Financial Stability Report 2024, Chapter 2. Washington, 2024.

Nature. “Digital Trade Exhibits a Pronounced Low-Carbon Effect.” Scientific Reports 55(6), 2024. Reuters. “EU Carbon Tariffs Loom as CBAM Takes Shape.” November 8, 2024.

UNCTAD. “Global Trade Hits Record $33 Trillion in 2024.” April 2025.

UNCTAD. Trade and Development Report 2024. Geneva, 2024.

UNEP. Emissions Gap Report 2024. Nairobi, 2024.

World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2025. Washington, DC, 2025.