Yoon Suk-yeol’s Impeachment Shakes South Korea to Its Core

Input

Changed

Yoon’s Martial Law Gamble Ends in Political Ruin Placement The Verdict That Divided a Nation An Unforgettable Moment in South Korea’s History

Yoon’s Martial Law Gamble Ends in Political Ruin Placement

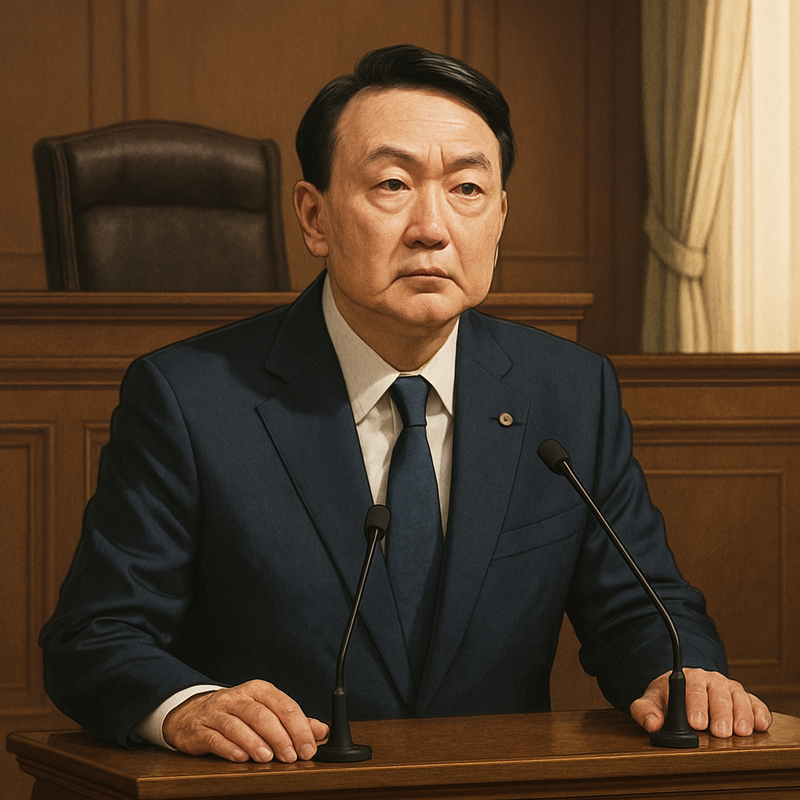

In a historic and unanimous decision on April 4, 2025, South Korea’s Constitutional Court removed President Yoon Suk-yeol from office, sealing the fate of a leader whose dramatic gamble with martial law backfired in the most spectacular fashion. The ruling — 8 to 0 — found that Yoon had “gravely violated the Constitution” by declaring martial law on December 3, 2024, a move that weaponized the military against opposition lawmakers and plunged the country into political chaos.

This verdict ends Yoon’s presidency just three years after he came into office, and thrusts the nation into uncharted political terrain. The court’s decision immediately triggered both jubilation and despair across the political spectrum, with many South Koreans taking to the streets — some to celebrate, others to vent fury. As the country prepares for a snap presidential election within 60 days, tensions are at a boiling point, and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

President Yoon’s decision to invoke martial law came at a time when his administration was facing severe resistance from an opposition-controlled National Assembly. On December 3, he declared that anti-state elements had infiltrated the government and that drastic measures were needed to protect national security. Tanks and armed troops were dispatched to surround the National Assembly building, effectively barring lawmakers from entering and paralyzing the legislative process.

Many saw this as a blatant attempt to cling to power after a bruising midterm defeat. Opposition parties swiftly condemned the move, and the first impeachment vote on December 7 narrowly failed due to a walkout by Yoon's allies. But just a week later, on December 14, a second motion succeeded — and with it, the presidency of Yoon was suspended pending a Constitutional Court review.

The gamble was audacious — and, as it turned out, recklessly miscalculated. Yoon had staked his presidency on breaking the political deadlock through force. Instead, he handed his opponents the very ammunition they needed to remove him from power.

In the days leading up to the Constitutional Court’s verdict, the air in Seoul was thick with anxiety. Supporters of Yoon, many of them elderly conservatives who had remained fiercely loyal, camped outside the court building, waving flags and holding banners that decried the impeachment as a political witch hunt. Simultaneously, thousands of anti-Yoon demonstrators flooded downtown avenues, demanding that justice be served.

There were fears — credible ones — that whatever the court decided would ignite riots. Authorities deployed thousands of police officers throughout the city. Barriers were erected around government buildings, subway stations were placed on high alert, and hospitals were asked to remain ready for emergencies.

In some corners, there were hopes that the Constitutional Court would rule in Yoon’s favor, or at least produce a split decision that would muddy the waters. Yoon's legal team had argued that martial law, while extraordinary, was constitutionally permissible under a perceived national security threat. Some of his supporters clung to that interpretation, praying for a reprieve.

But the reality was that the court’s decision — though harsh — was exactly what most observers had expected. The justices wrote that Yoon’s declaration was “a severe and unjustified suspension of the constitutional order.” Acting Chief Justice Moon Hyung-bae stated emphatically: “The president must protect the Constitution, not trample it. His actions caused irreparable harm to the democratic system.”

The Verdict That Divided a Nation

The fallout from the decision was immediate. Within hours, supporters of the former president began clashing with police, shouting “Yoon was right!” and accusing the judiciary of political bias. Simultaneously, opposition supporters danced in the streets, embracing each other and waving South Korean flags, chanting “Democracy has won!”

The divide is stark. And as someone who has lived through the democratic struggles of the 1980s, the economic shocks of the Asian Financial Crisis, the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye, and numerous massive street protests — I can say without hesitation that I have never witnessed this level of national tension. The sheer number of people spilling onto the streets in central Seoul this week is unprecedented. Entire subway lines were packed from early morning to nightfall. In the plaza outside the Constitutional Court, there were people openly weeping — some with relief, others with rage.

As night fell on April 4, the atmosphere became more charged. Candles were lit by those celebrating, while loudspeakers blasted patriotic anthems from protest trucks belonging to pro-Yoon factions. Riot police formed human shields between the two groups, barely preventing physical confrontations. The country feels like it’s walking a tightrope — just one spark away from mass unrest.

With Yoon removed, Prime Minister Han Duck-soo has taken on the role of acting president. The constitution mandates a new presidential election within 60 days, and the National Election Commission has already set the tentative date for June 3. This will be the third presidential election in less than a decade — a reflection of how volatile South Korean politics has become.

Meanwhile, Yoon faces a legal quagmire. He is scheduled to appear in court starting April 14 to answer charges including insurrection, abuse of power, and obstruction of constitutional rights. If convicted, he could face life in prison or even capital punishment — although South Korea has maintained a moratorium on the death penalty since 1997.

The upcoming election is shaping up to be the most consequential in decades. On one side stands Lee Jae-myung, the progressive leader of the Democratic Party, who narrowly lost to Yoon in 2022. Despite ongoing legal challenges over alleged corruption, Lee remains a favorite, riding a wave of public dissatisfaction with conservative governance.

On the other side, the conservatives are in disarray. Han Dong-hoon, the former People Power Party chair who resigned over the martial law crisis, is a likely candidate. Though he distanced himself from Yoon's actions, he must now unify a fractured base. Other possible conservative contenders include Seoul Mayor Oh Se-hoon, known for his hawkish foreign policy, and Hong Joon-pyo, a seasoned political brawler from Daegu.

Whoever emerges victorious will inherit a nation wounded by division, burdened by economic pressure, and navigating global turbulence — not least from the 25% tariffs recently slapped on South Korean imports by the Trump administration in Washington.

An Unforgettable Moment in South Korea’s History

After more than four decades of observing and writing about this country’s political upheavals, from the democratization protests of the 1980s to the candlelight revolutions of the 2010s, I thought I had seen it all. But what unfolded this past week has defied all expectations.

I have never — not once in my life — seen this many people on the streets. I have never felt this much collective tension in the air. It's not just politics anymore; it’s something deeper, more existential. It’s about the very soul of Korean democracy.

People are afraid. People are hopeful. People are angry. People are proud. It’s a swirling storm of emotion unlike anything in recent memory. As chants ring out in Gwanghwamun Square and tears fall in front of the Supreme Court, one thing is clear — South Korea is not going back to the way things were.

What comes next will be one hell of an election — one that will test the foundations of South Korea’s democracy, its institutions, and its people. The stakes are existential, the wounds still raw. The political establishment must now prove that the system can hold, even under the strain of crisis.

This isn’t just about replacing a president. It’s about choosing what kind of country South Koreans want to live in — one governed by the rule of law and democratic norms, or one where power is seized under the guise of national emergency.

The world will be watching. And so will the people — millions of them, crowding the streets, casting their ballots, raising their voices. The winds of change are howling through Seoul. And in this moment, more than ever, South Korea stands at a crossroads.