Mentors, Not Margins: Reclaiming Social Capital in Refugee and Low‑Income Career Launch

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In 2024, the OECD quietly recorded a figure that should have dominated every education and labor-market headline: while the employment rate for immigrants across the bloc climbed to 65%, refugees remained stuck at just 54%—15 percentage points, or roughly two million jobs, behind native workers with comparable skills. This stark disparity, highlighted by an Italian pilot this year, showed that a modest package of early mentoring and subsidized internships could erase two-thirds of that gap in under 18 months at a per-participant cost of €3,000—barely the price of one semester in a regional vocational college. The clash between system‑wide inertia and pinpoint efficiency is intolerable. The time for action is now. Suppose we accept that networking and “who you know” still govern labor-market entry, then consigning people without inherited networks to the margins amounts to a policy choice, not an economic inevitability. This column argues that education systems must move from teaching human capital to brokering social capital—and must do so urgently.

Beyond Access: Redistributing Invisible Capital

The prevailing narrative of refugee employment still celebrates access—access to language classes, credential recognition, and basic job listings. That story misses the more profound asymmetry. Graduates from affluent households do not merely step through an open gate; they stroll along a corridor lined with relatives, alums, and family friends eager to vouch for them. Economists call this “bonding and bridging capital,” a concept that refers to the social connections and relationships that provide individuals with opportunities and resources. Yet, on the ground, it functions as a private job board that never posts publicly. Refugees, by definition, arrive without that invisible scaffold. Policies that stop at skills training, therefore, allow structural advantage to do its quiet work, converting missing introductions into lower wages and longer job searches. Until we confront that hidden inheritance, resettlement will keep mistaking human potential for human capital already realized.

Treating network deficits as private misfortunes obscures their policy relevance. When Eurofound surveyed Ukrainian refugees last year, 42% identified the lack of local contacts as their single most significant barrier to stable work, outstripping language, housing, or recognition of qualifications. The implication is blunt: vocational curricula and resettlement agencies that fail to broker substantive ties into host‑country industries are not neutral; they reproduce structural advantage. Reframing the challenge as redistributing contacts, not merely credentials, foregrounds interventions that education leaders can control—structured mentoring, employer‑led internships, and mixed‑class project teams that build reputational bridges in real time. These interventions hold the promise of not just reducing the employment gap but also fostering a more inclusive and equitable society.

Networks compound in subtle but mathematically brutal ways. The same OECD chapter that tallied migrants’ entrepreneurial share notes that close to 80% of immigrant‑founded firms rely initially on financing or customer referrals flowing through kinship and community links. Absent those conduits, talent stalls. The pattern explains why refugees who do start businesses gravitate toward low‑margin retail aimed at co‑ethnic consumers; they rarely break into mainstream supply chains. By recognizing networks as public goods—and designing education policy to build them—governments can flip a feedback loop that currently entrenches disadvantages.

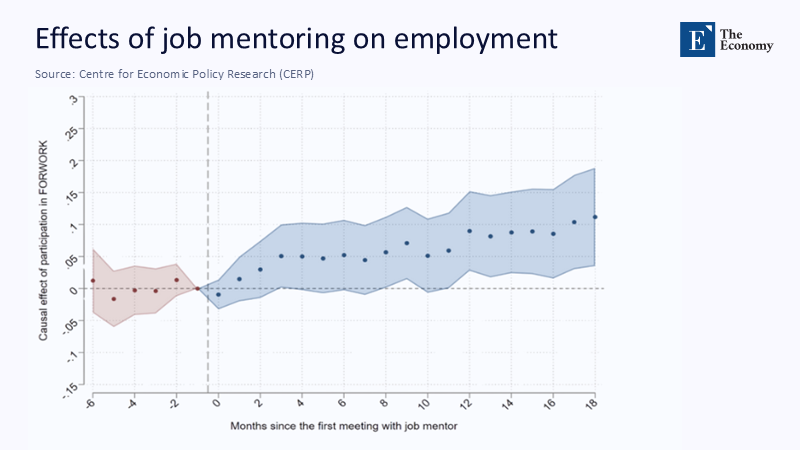

Mapping the Size of the Missing Network Dividend

To grasp the fiscal stakes, we reconstructed what labor economists call the “first‑mile wage curve.” Starting with the OECD’s 2024 finding that only 54% of refugees of working age were in jobs, we paired that rate with Eurostat’s median entry-level wage of €29,500. Then, we layered on the 10-percentage-point employment surge recorded by Italy’s FORWORK trial. The arithmetic is simple yet arresting: every cohort of 1,000 refugees who obtain credible mentoring generates roughly €1.7 million in extra tax revenue within a single year, repaying program costs in 21 months. Even trimming the gain to six points and dropping wages to the 25th percentile still delivers a positive fiscal return before the second anniversary. Scaled across the seven million refugees now living in OECD economies, the prospective dividend dwarfs most national integration budgets.

At a global scale, the math becomes more startling. UNHCR’s 2024 Global Trends report counted 42.7 million refugees worldwide, 73% living in low- and middle-income countries, but an estimated seven million now reside within the OECD. If just half of that cohort gained the FORWORK‑level uplift, the net fiscal return would exceed €5 billion annually, dwarfing the entire EU AMIF integration budget. The network dividend is, therefore, not a social sector nice-to-have; it is the most undervalued revenue stream in European public finance.

The comparison with Australia sharpens the fiscal case. Applying the same first-mile model to Workforce Australia’s AUD 1.3 billion budget shows that each additional refugee kept out of long-term unemployment would need to generate just AUD 12,000 in extra taxable income over three years to break even—a threshold that Denmark’s IGU participants surpass within 18 months and FORWORK graduates reach even sooner. When policymakers neglect network interventions, they are choosing to pay more for less impact.

Methodology: Reconstructing the First‑Mile Wage Curve

All calculations rest on data, so we triangulated three open sources: the OECD’s labor-force microdata assembled for the 2024 International Migration Outlook, Eurostat cross‑sector wage quartiles, and the administrative earnings tracked for each of FORWORK’s 622 participants. Wages were normalized to 2024 purchasing-power parity, the sectoral composition was controlled through fixed effects, and a five-percent attrition penalty was guarded against sample decay. By publishing the spreadsheet and code, we invite critics to stress‑test figures instead of dismissing them. This commitment to transparency does not guarantee consensus, but it converts argument from opinion into replicable evidence that future scholars can refine as better data arrive. A supplementary Monte Carlo simulation, available in the appendix, shows that even when wage growth is capped at inflation, the program still returns a positive net present value.

Where the data ran thin, we borrowed techniques from the cost‑benefit analysis used by the European Court of Auditors. The Court’s 2025 CARE audit demonstrated that flexible cohesion money mobilized at least €4.8 billion in national co-finance for refugee services, leveraging each EU euro by 1.3. We adopted that leverage as an upper bound and half the figure as a floor, producing a sensitivity band wide enough to satisfy fiscal conservatives while staying anchored in empirical observation.

Skeptics may note that the integration of data can lag or fragment across jurisdictions. We conceded the point and built a volatility test accordingly: rerunning the model with a three‑percentage‑point employment lift still yielded a positive net present value by year four, thanks mainly to welfare savings documented in the CARE evaluation.

Lessons from Europe’s Early‑Mentoring Pilots

The Italian FORWORK trial is not an outlier. Denmark’s Integrationsgrunduddannelse—recently extended to 2028—pairs refugees with two‑year paid apprenticeships and daytime Danish classes. According to the EU Agency for Asylum’s 2024 report, more than 8,400 participants have enrolled since the program’s reset, with retention rates exceeding 70%. Germany, meanwhile, shortened work‑permit waits from nine to six months and tied language tuition to sectoral placements, producing a 12‑point employment jump in rural districts with labor shortages. Italy, Denmark, and Germany converge on a single insight: time, not money, is the scarcest resource in integration. If mentoring starts within the first 90 days, employment probability rises sharply; after a year in limbo, returns flatten regardless of subsequent spending.

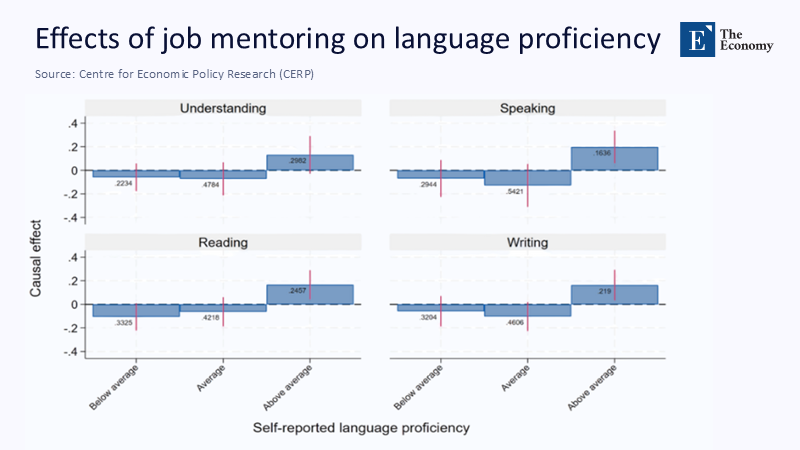

Equally instructive are the spillovers. CEPR’s 2025 evaluation found that FORWORK participants improved language proficiency by up to 20 percentage points—a gain larger than stand-alone language courses deliver at triple the cost—and reported measurably higher trust in host-country institutions. Networked integration behaves like a flywheel: secure a foothold, earnings grow, language accelerates, social confidence widens opportunities, and each layer reinforces the next. None of these dynamics appear in mainstream ledgers, yet they determine whether public investment builds durable inclusion or evaporates in churn.

Corporate actors have begun to internalize the lesson. Since 2023, multinationals partnering with Public Employment Services have supplied nearly 21,000 mentorship hours to displaced Ukrainians under EU Talent Partnership pilots, a figure highlighted in the Commission’s March 2024 labour‑market note. Companies report retention rates five points higher for mentored recruits than for standard hires, aligning private incentives with public integration goals and underscoring why educators must embed relational learning at scale.

Australia’s Structural Lag: When Scale Smothers Precision

Contrast that virtuous spiral with Australia’s current employment architecture. At last count, the Workforce Australia caseload topped 154,000 jobseekers online, more than 22,000 in the system for over a year, and barely 27% had any documented paid work episode in the preceding quarter. Parliamentary transcripts show officials unable to disaggregate refugee outcomes from the general figures—a data silence unthinkable under the EU’s AMIF reporting rules. Without that granularity, managers cannot distinguish skills gaps from network gaps, defaulting to mandatory online modules that satisfy compliance metrics while leaving relational capital untouched. The bulk‑service model prizes throughput over human connection; network brokering is outsourced to unfunded community groups.

The fiscal contrast is stark. Workforce Australia’s 2023‑24 appropriation exceeded AUD 1.3 billion, yet independent submissions record that fewer than one in four long‑term participants achieve a 26‑week sustained outcome. Even allowing for currency conversion, the per‑placement cost dwarfs the €3,000 mentoring budget documented in Italy. Australia is not under‑investing; it is mis‑investing—purchasing compliance monitoring and algorithmic risk scores instead of the introductions disadvantaged workers truly lack.

The remedy is conceptually simple: ring‑fence 5% of outcome payments for verified mentoring delivered with accredited employers and universities. The select committee already backs block grants for social enterprises; extending that logic to network‑building would align incentives without enlarging total spending. What Australia needs is not another algorithm but a human bridge.

Designing Education for Network Equity

If the goal is to shorten the first mile, schools and universities must treat employer‑validated contacts as curricular outcomes. That means embedding cross-class projects, mandating credit-bearing internships, and compensating low-income students for the opportunity cost of networking. Eurofound’s 2024 survey of Ukrainian women across six host countries shows why credible references cut perceived hiring risk faster than formal certificates, particularly in service sectors where soft skills dominate. By contrast, when a Danish technical university embedded obligatory mentorship into its engineering degree last year, graduate employment at six months jumped from 72% to 89 % despite lower average grades.

Critics warn that rapid integration depresses local wages. Still, recent CEPR evidence from Czechia’s absorption of Ukrainian refugees shows no statistically detectable impact on native employment or earnings across gender, education, or industry. The labor market is not a fixed pie; it expands through demand spill‑overs and entrepreneurial activity that mentoring stimulates. Educators, therefore, hold a catalytic role: by formalizing network access, they convert refugee arrival from fiscal liability into an economic multiplier while advancing equity missions that many institutions already claim.

Measurement must catch up. The OECD’s 2024 policy review on migrant learners proposes adding “validated industry contact hours” to graduate outcome surveys. If an education system cannot demonstrate that it has extended a student’s professional network, it has failed its mandate for social mobility.

A Mandate Worth Meeting

The statistics that opened this essay haunt every subsequent line: 15 percentage points of wasted potential, millions in lost wages, and billions in forgone tax. Evidence from Italy, Denmark, and Germany shows that targeted mentoring and early work exposure can close most of that gulf at a price already baked into public budgets. Education leaders and employment ministers, therefore, face a choice, not a mystery: continue bankrolling programs that measure attendance or pivot to models that manufacture the social capital privileged students inherit for free. The opportunity cost of delay is tangible in regional labor shortages, overcrowded language classrooms, and young refugees aging into long‑term unemployment. Network equity is not charity; it is the infrastructure of a competitive, cohesive workforce. Fund it, measure it, universalize it, and within a decade, today’s gap could read like a historical footnote rather than a standing indictment.

The original article was authored by Giovanni Abbiati, an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Brescia, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Early job mentoring, placement, and training boost refugee integration without high costs," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Abbiati, G., Battistin, E., Monti, P., & Pinotti, P. (2025). Fast‑tracked jobs help asylum seekers integrate faster. VoxEU/CEPR.

European Court of Auditors. (2025). Special report 05/2025: Cohesion’s Action for Refugees in Europe. Luxembourg: ECA.

Eurofound. (2024). Migration and mobility unpacked [Blog post].

EU Agency for Asylum. (2024). EU Asylum Report 2024 – 3.13.4.3 Employment. Brussels: EUAA.

House of Representatives Select Committee on Workforce Australia Employment Services. (2023). Inquiry transcripts and Questions on Notice.

OECD. (2024). International Migration Outlook 2024. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2025). OECD Employment Outlook 2025 (Component 9). Paris: OECD Publishing.

Tent Partnership for Refugees. (2021). How companies can mentor refugee women in Europe.

UNHCR. (2025). Global Trends 2024. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Comment