The Pedagogy of Private Equity: Why the Real Lesson Is About Human Capital, Not Headcount

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Private-equity-backed firms now write paychecks for more than 12 million US workers, a population larger than the entire federal civil service. Yet, those same workers face average wage losses of roughly 10% within twelve months and 18% within three years of a buy-out. This coexistence of swelling payrolls and shrinking paycheques is not a rounding error; it is the signature of an ownership model that rewards financial engineering over human capital compounding. The dissonance matters because wages are the visible tip of a deeper iceberg: when earnings slide, so do training budgets, career ladders, and the tacit knowledge that underwrites long‑run productivity. As policymakers scramble to future‑proof a workforce facing generative AI and demographic headwinds, ignoring what is happening inside the most significant single block of privately controlled employers is an educational failure of the first order. Private equity is no longer a side story on Wall Street; it is the hidden curriculum shaping Main Street’s skills ecosystem, and that curriculum urgently needs rewriting.

From Payrolls to Human Capital: Reframing the Private‑Equity Debate

The familiar quarrel over whether private equity (PE) kills or creates jobs risks mistaking enrollment for learning. Job counts are the attendance sheet; skills acquisition is the syllabus. By examining longitudinal employee-level data, the latest CEPR research shows that the sharpest earnings decline after buy-outs falls on those who exit the target firm, suggesting that PE ownership truncates not only pay but also tenure-based learning curves. Reframing the debate means shifting our policy lens from sheer employment numbers to the quality and trajectory of the human capital embedded in those jobs. In an economy where productivity growth increasingly flows from tacit, team‑based know‑how, that distinction is consequential.

Why does this reframing matter now? Because the labor market is decoupling. On the one hand, the McKinsey 2025 Global Private Markets Report flags a renewed investor appetite for buy-outs even in higher-rate environments; on the other, HHS data tie PE ownership in nursing homes to an 11% jump in resident mortality. When deals are restarting at scale while human‑capital externalities surface in life‑and‑death metrics, the cost of misunderstanding what PE changes inside firms balloons from abstract theory to public health urgency. We should be asking not merely whether PE adds or subtracts jobs but whether it expands or erodes the economy’s capacity to learn.

Reading the Numbers Anew: What the Latest Evidence Reveals

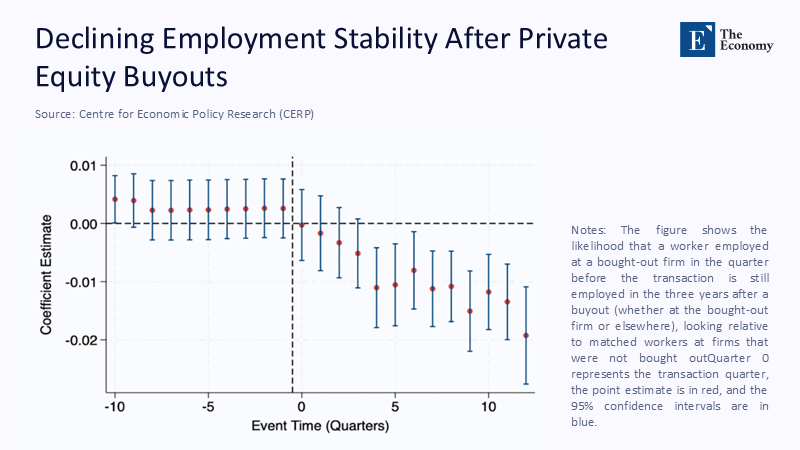

The newest matched-worker panel assembled by Herkenhoff et al. tracks 2.5 million employees across 3,600 US buy-outs and confirms a 1-to-2 percentage-point rise in unemployment relative to peers. Wages fall steeply for movers but barely budge for stayers, contradicting the monopsony hypothesis and instead pointing to selective displacement: the productivity‑enhancing plants remain, and the knowledge‑specific ones shutter. Methodologically, the authors exploit the Longitudinal Employer‑Household Dynamics (LEHD) microdata, controlling for pre‑buy‑out wage trends and local labor‑market shocks, thereby isolating the ownership effect.

Complementing this micro view, the Emerging Data Collaborative Initiative (EDCI) reports that PE portfolio companies nevertheless added four net new hires per 100 existing employees in 2024, outpacing public peers even amid a deal slump. The key to reconciling the two findings is churn. Gross hiring masks targeted cuts and re‑allocations that disproportionately hit mid‑career staff—the very cohort most likely to mentor juniors. When we weigh jobs by tenure and training intensity rather than headcount, the apparent job‑creation premium flips sign, indicating a latent drain on firm‑specific human capital.

Efficiency, Elasticity, and the Unseen Cost of Short‑Termism

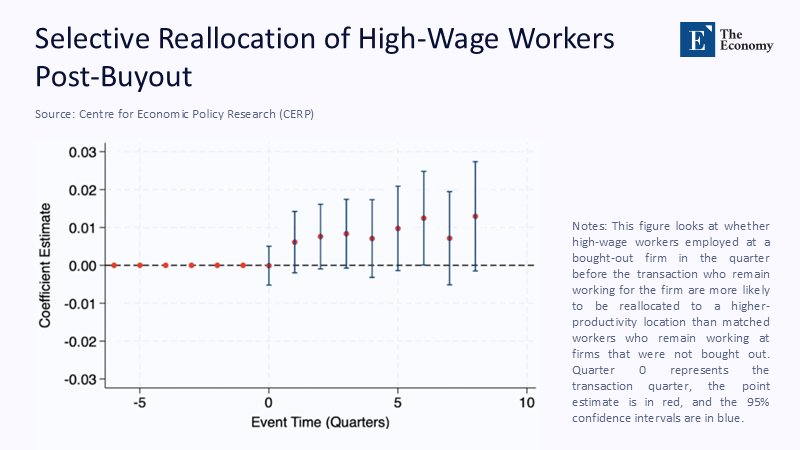

Private equity’s defenders celebrate plant‑level efficiency gains: the NBER census‑linked study finds that PE owners downsize low‑productivity facilities first, reallocating high‑wage employees to better plants.

At face value, that looks like textbook re‑optimization. Yet every layoff also liquidates embedded know‑how that rarely migrates intact. Nursing home data illustrate the trade-off vividly: after PE acquisition, residents become 11% more likely to die, a result tied, according to HHS, to staffing cuts and skill dilution rather than capital scarcity. Efficiency measured in EBITDA ignores the negative externalities when the product is cared for or when lost tacit knowledge depresses adjacent suppliers’ productivity.

Where complex numbers are scarce—training budgets, mentorship hours—we can triangulate. Average training expenditure in US manufacturing runs about 2.5% of payroll. Applying the documented 10% wage hit to a 500-employee plant implies roughly $350,000 less annual training, assuming constant ratios. Even a conservative elasticity of 0.4 between training spend and productivity suggests a two‑to‑three‑year horizon before output losses outweigh the initial cost savings. Transparent back‑of‑the‑envelope estimates like these matter because they show educators and economists alike that the invisible line item of learning can—and should—be brought into the financial calculus.

Lessons from Deadspin to Steward Health: Case Studies in Corporate Pedagogy

Numbers are abstract; stories stick. When Great Hill Partners bought the Gawker portfolio, management’s “stick to sports” edict provoked a mass resignation at Deadspin. Within weeks, the newsroom’s knowledge network—cultivated over the years—was vaporized. The episode is more than labor drama; it is a parable of organizational learning. Culture, editorial judgment, and institutional memory walked out the door, leaving monetizable page views but little capacity for reinvention.

Healthcare offers a darker mirror. Steward Health Care, bankrolled by Cerberus, filed for bankruptcy in August 2024 after years of asset stripping that left bills unpaid and clinicians fleeing. Here, too, the value was extracted by draining the stock of human capital—physicians, nurses, back‑office specialists—until the system collapsed. The pattern across both cases is pedagogical: when owners treat labor as a cost bucket, the organization stops teaching itself how to improve. The loss is cumulative, compounding silently until it breaches the surface in closure or catastrophe.

Designing Policies That Reward Learning, Not Just Earnings

For educators tasked with preparing learners for evolving workplaces, the lesson is clear: curriculum must include bargaining literacy and data fluency so graduates can audit the learning climate of prospective employers. University career centers can start publishing “training intensity indices” sourced from alumni surveys, nudging firms toward transparency. Administrators overseeing public colleges—often among the largest local employers—should benchmark their procurement against vendors’ training commitments, penalizing serial churn.

Policymakers have the heaviest lift. Three levers stand out. First, tie the favorable tax treatment of carried interest to demonstrable year‑over‑year growth in per‑employee training spend, not just EBITDA. Second, expand the nascent Ownership Works model—in which firms like Blackstone granted equity to 18,000 Copeland workers—by making employee-ownership dilution clauses a prerequisite for Small Business Administration debt guarantees. Third, require companies above a given leverage ratio to disclose an audited “human‑capital continuity statement” covering layoffs, training hours, and voluntary exit rates—metrics that investors ignore at their peril but educators and regional planners desperately need.

Pre‑Empting the Counterargument

Skeptics will note—correctly—that the same McKinsey report recording layoffs also shows investors continuing to outperform the S&P 500 over twenty‑five years and that operational turnaround can salvage failing assets. They will point to job‑creation metrics and ownership models that share the upside with workers. All true, but partially true. The EDCI job‑creation figure, for instance, captures gross hires, not the senior journeymen whose departure deprives juniors of mentorship. Moreover, equity‑sharing pilots cover barely 1% of PE‑owned firms, according to PESP’s updated employer tracker. The exception does not overturn the rule.

Another objection—efficiency—is equally incomplete. Yes, reallocating labor improves plant productivity; the NBER evidence shows that explicitly. Yet when mortality rises or when a newsroom’s voice evaporates, externalities shift costs to patients, readers, and taxpayers. The policy question is, therefore, not whether efficiency gains exist but whether current accounting systems price the destruction of shared intellectual capital. They do not, and until they do, the claim that PE merely “optimizes” remains at best a half‑truth.

Toward a Stewardship Standard

If swelling payrolls and shrinking paycheques headline the private‑equity story, the subtext is an unchecked erosion of the nation’s learning infrastructure. We began with the stark figure—12 million workers, double-digit wage losses—and the argument comes full circle: what appears as a compensation issue is, in fact, a curriculum issue in disguise. The call to action is therefore shared. Educators must teach future employees to audit a firm’s learning climate; administrators must procure with human capital metrics in mind; lawmakers must hard‑wire training incentives into the tax code. Private equity, for its part, should adopt a stewardship standard that counts skills retained and developed alongside dollars deployed. Until that happens, the industry will continue to ace the balance sheet exam while failing the deeper test of long‑term value creation. The following syllabus for American competitiveness demands better teachers and better owners.

The original article was authored by Kyle Herkenhoff, an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Minnesota, along with four co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Understanding the impact of private equity on employees," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bain & Company. (2025). Private Equity Outlook 2025: Is a Recovery Starting to Take Shape?

Business Insider. (2024, Oct 11). How Blackstone Made 18,000 Workers Owners of Their HVAC Company.

Goodwin Recruiting. (2024). The Rise of Private Equity Firms in 2024.

Herkenhoff, K., Lerner, J., Phillips, G., Rebelo, F., & Sampson, B. (2025). Understanding the Impact of Private Equity on Employees. VoxEU/CEPR.

McKinsey & Company. (2025). Global Private Markets Report 2025.

Mitchenall, T. (2024). Private Equity‑Owned Companies Still Set the Pace for Job Creation. New Private Markets, Oct 23, 2024.

Pension & Extractive Stakeholder Project (PESP). (2024). Largest Private Equity Employer Database Update.

The Guardian. (2025, Feb 6). US Health Department Condemns Private Equity Firms for Role in Declining Healthcare Access.

The Nation. (2019, Nov 5). This Is a Horror Story: How Private Equity Vampires Are Killing Everything.

The New Yorker. (2024, Dec 12). The Gilded Age of Medicine Is Here.

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2025). Private Equity and Patient Outcomes Report.

Comment