Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

External shocks mostly cripple places, not people. When a region's institutions, markets, and civic networks break down, the fastest and most reliable insurance policy is migration—sometimes across provinces, oceans, and invariably across opportunity gradients. History consistently shows that people adapt; places often don’t. The future of intergenerational prosperity lies in enabling human mobility, not in clinging to a sentimental attachment to a specific geographic location.

The Evidence: Why Mobility Outpaces Place Recovery

The CEPR/VoxEU study “Place Prosperity versus People Prosperity” follows families caught in China’s 17th-century Ming-to-Qing upheaval and again in the 20th-century Communist-era land reforms. Five centuries apart, the result is identical: descendants who left distressed prefectures recouped status within two generations; those who stayed remained poorer three centuries later. In other words, the human potential remained intact—the institutions and economic scaffolding of those places failed.

Modern panel data reinforce the point. Opportunity Insights’ Changing Opportunity project, which links 57 million U.S. tax records with census and education files, shows that children who moved from low-employment to high-employment counties before age thirteen enjoyed earnings gains of up to $8,000 a year relative to similar stayers. These "mover gains" persist even after controlling for parental education, race, and local unemployment rates.

These findings form the backbone of the people-versus-place debate: geography doesn't determine destiny—mobility does.

The “passport objection” and why it fails only on timing

Skeptics argue that internal migration (as in the Chinese context) fundamentally differs from international migration, which adds language barriers, legal hurdles, and cultural divides. This is the so-called' passport objection', which suggests that the challenges of international migration are significantly greater than those of internal migration.

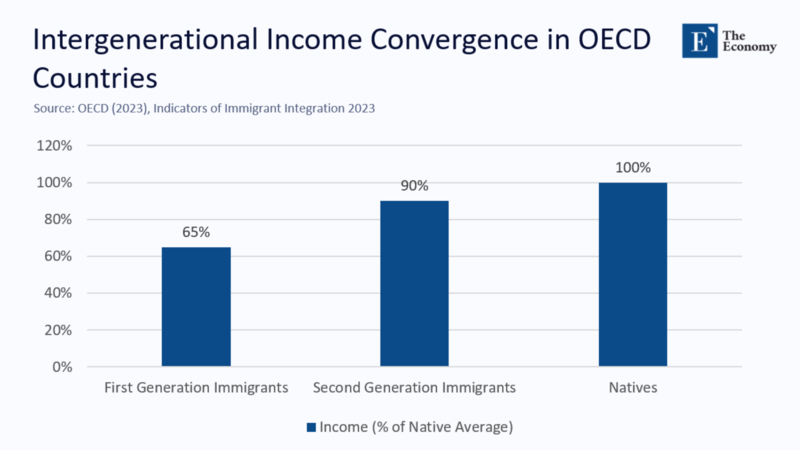

Authentic, initial earnings dips are sizable. The OECD’s 2023 Indicators of Immigrant Integration report indicates that first-generation migrants earn about 65% of natives’ pay, on average, across member states. The gap reflects not just skill mismatches but also discrimination and credential non-recognition. Yet the same dataset finds that their children close three-quarters of the gap by adulthood, reaching roughly 90% of native incomes by generation two.

This means the mobility engine still works; it merely needs an extra generational gear shift when race, language, or legal status add friction. The story of international migrants is not stagnation but delayed convergence.

Importantly, this intergenerational climb is not automatic. It depends on supportive policy environments, quality of schooling, and access to the labor market. But when those are present, immigrants recover ground surprisingly quickly.

A closer look: Britain’s Indian diaspora as a two-generation case study

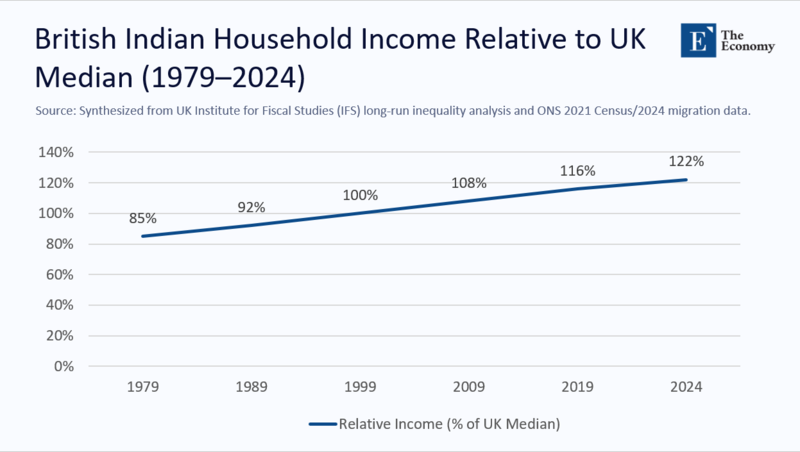

Britain offers a live demonstration of long-run convergence under maximum cultural distance. The Office for National Statistics places the resident Indian ethnic group at 1.8 million in England and Wales on the 2021 Census. It reports a further net inflow of 240,000 Indian immigrants in the year to June 2024.

Within that cohort, median household income now sits 22 percent above the national median, compared with a 15 percent deficit in 1979. This reversal of fortune is neither accidental nor short-term: it reflects a generation of investment in education, occupational mobility, and community infrastructure.

Culturally, the community has traversed the ultimate ceiling: Rishi Sunak, grandson of Kenya-born Indian migrants, became Britain’s first Hindu prime minister in October 2022—fifty-five years after the Commonwealth Immigrants Act restricted non-white entry. While Sunak's rise is extraordinary in pace, it is consistent with broader trends in the socio-economic integration of British Indians.

His parents climbed into the professional class within a single generation; he entered Oxbridge, then Stanford finance; his daughters will start from a baseline of elite networks indistinguishable from long-established British peers. The "place effect" of post-industrial Southampton slowed, but it did not override the mobility arithmetic of relocating to London’s global labor market.

The implication is that race and immigration status may delay the timeline, but they rarely derail the direction of progress.

Why do places ossify while people reboot

Why can't places recover the way people do? Three reasons:

Network fragility: Modern production relies on dense supplier and knowledge networks. A local shock—like warfare in 17th-century Shanxi or an automotive downturn in 21st-century Detroit snaps multiple links simultaneously. Rebuilding these ties requires massive coordination and capital, which individuals cannot initiate alone.

Institutional hysteresis: Once a region becomes risk-averse or politically gridlocked after a crisis, it often repels the investment it needs. This institutional memory of failure—what economists call hysteresis—becomes self-reinforcing.

Demographic echo: When the skilled and mobile leave, those remaining are older, less educated, and more dependent on public services. This makes tax revenues shrink while welfare demands increase, locking the region into a fiscal trap.

The result? Even decades after a shock, formerly prosperous places often struggle to recreate the conditions for upward mobility.

Policy design that works with human mobility, not against it

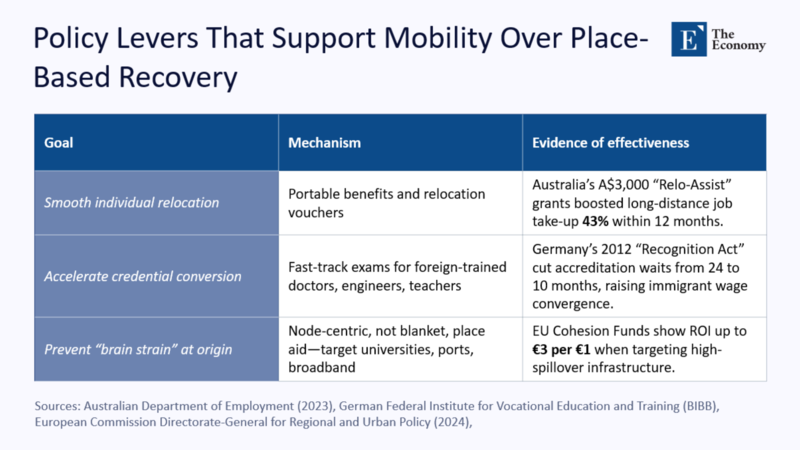

If migration is a rational response to geographic decline, then policy should make moving easier and more rewarding. Here's how:

Rather than pouring endless funds into failing geographies, policymakers should make it easier for people to leave and invest only in place-based assets that create long-term returns.

Mobility is not a failure of localism—it is a rational strategy for intergenerational insurance.

Reconciling race and class in the migration narrative

Opportunity Insights finds that class gaps have grown while race gaps have shrunk in recent U.S. cohorts, particularly for those who have migrated to higher-opportunity counties. Peer effects primarily drive this improvement: children benefit when surrounded by classmates whose parents work and have stable incomes.

This matters because it reframes the debate between race and class. Race does not negate the benefits of mobility, but it does impose extra barriers: language acquisition, name-based discrimination, legal status insecurity, and religious differences. These factors stretch the timeline for mobility but not its direction.

Communities that bridge these divides—via interethnic friendships, public schooling, and inclusive institutions—accelerate the catch-up process.

Conclusion: Follow the opportunity—and build for a return

External shocks expose places' structural brittleness but rarely extinguish people's adaptive genius. Archival Chinese records, modern tax-return big data, and Britain’s live immigrant experiment all converge on a single insight: when opportunity moves, follow it.

The most resilient societies make this process easier by lowering the cost of mobility for individuals while rebuilding regional nodes that make places worth returning to. Emigration is not an act of despair but an agency vote. Betting on people isn’t just good policy; it’s good history.

In the 21st century, the strongest nations will treat mobility as a multiplier, not a menace. The policy question is no longer whether people should move—they already do. The question is whether our systems can keep up with their ambition.

The original article was authored by Carol Shiue and Wolfgang Keller. The English version of the article, titled " Place prosperity versus people prosperity: Migration and the intergenerational transmission of knowledge,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.