Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

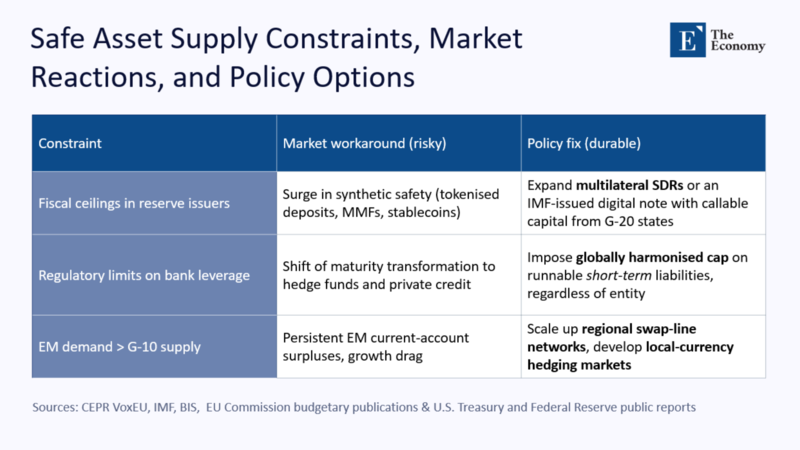

The financial system’s most dangerous habit equates labeled safety with actual safety. When demand for low‑risk paper outruns the supply, sovereigns are politically able to print, and the private sector manufactures look‑alikes, often by stacking hidden leverage behind a triple‑A wrapper. That alchemy works immediately when investors decide to test the wrapper, usually when they need the money most.

Today’s safe‑asset conundrum is no longer confined to trans‑Atlantic markets. Emerging‑market (EM) reserve managers, sovereign wealth funds, and tech‑sector cash piles all want high‑quality collateral, while advanced‑economy governments face rising debt‑service costs and voter fatigue. Unless policymakers find a credible way to expand the world’s stock of genuine safety, the next “dash for cash” could start in rock-solid places.

Two species of safety—and why they matter

Economists treat safe assets as homogenous, but investors do not. Markets distinguish between sovereign safety—grounded in taxing power, currency issuance, and legal sovereignty—and engineered safety, in which private intermediaries promise par convertibility by holding supposedly offsetting risk on their balance sheets. The latter is cheaper to produce, so it proliferates whenever it is scarce.

A recent VoxEU study illustrates how this mix evolves over the cycle: sovereign bills dominate the pool after every crisis, while private-label “safe” products reemerge during expansions, increasing from roughly 10 percent of outstanding safe collateral in 2000 to almost 40 percent on the eve of the 2008 crash. The pattern suggests a systemic safety shortage that finance addresses by leveraging existing public instruments rather than introducing new ones.

The demand shock from the Global South

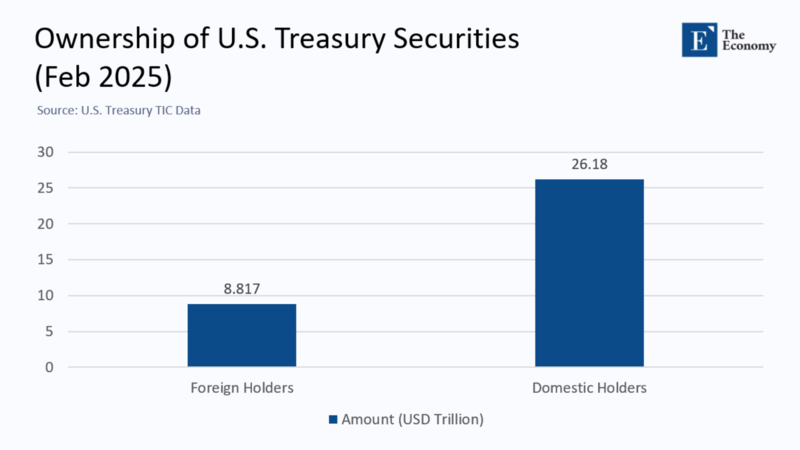

Since China’s WTO entry in 2001, the world has run a persistent capital-account deficit vis-à-vis emerging markets (EMs): every year, an average of 1–1.5 percent of global GDP flows into mature-economy government paper. Even after a quarter-century of reserve diversification, the February 2025 TIC data showed that foreign official and private holdings of Treasuries totaled $8.817 trillion. The bar chart below shows the result: foreigners now own a quarter of the $35 trillion Treasury stock. That share would be higher still if the Fed had not absorbed vast quantities of bonds through quantitative easing.

Why do EMs outsource safety? Partly because their currencies lack a long track record of stability, but mainly because safe assets double as international money. Dollar-denominated trade invoicing, commodity pricing, and cross-border bank funding all amplify the attraction of US paper, creating a positive feedback loop: the more the world needs dollars, the safer Treasuries appear, and vice versa.

When private finance fills the gap

Wall Street met the pre‑2008 demand boom by slicing risky mortgages into tranches and having rating agencies declare the top layer risk‑free. Investors bought the label; banks warehoused the tail risk. As defaults correlated, the engineered safety evaporated, triggering the fire‑sale dynamic we now call the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

The moral is not that structured finance is evil—mortgage securitization has social value—but that maturity transformation in disguise is an inherently fragile way to create collateral. Every run on money‑market funds or repo chains since 2008 follows the same script: nominally safe liabilities, backed by pro‑cyclical collateral, suddenly fail the only test that matters—convertibility at par in stress scenarios.

Governments: credible but not infinite suppliers

Public debt overcomes this fragility because it is ultimately backed by taxation. Yet even sovereigns hit hard limits:

- Arithmetic: once the real interest rate exceeds real growth, the debt‑to‑GDP ratio explodes mechanically. The IMF now lists seven advanced economies—including the US and Italy—where that tipping point could arrive this decade.

- Politics: voters balk at servicing unseen foreign creditors. Treasury interest tops $1 trillion annually in the United States, fuelling populist calls to “cap Wall Street’s allowance.”

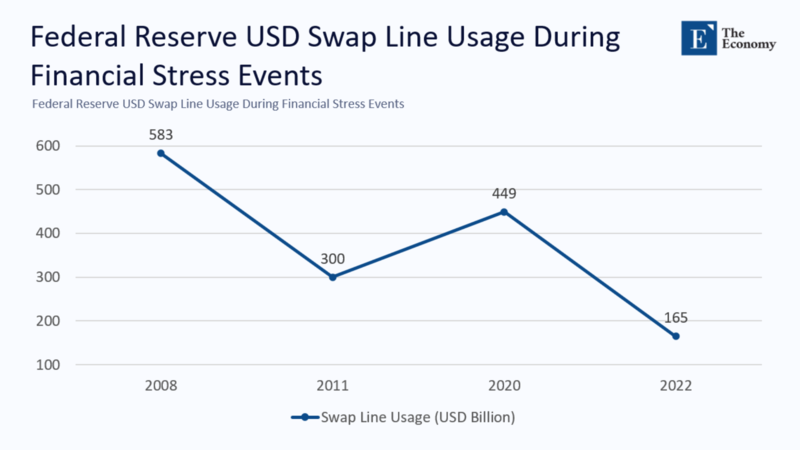

- Global‑public‑good externality: the hegemon’s currency is everyone else’s war chest. During COVID-19, the uptake of the Fed’s dollar swap lines hit $449 billion, five times Germany’s entire 10‑year Bund issuance that year. Supplying global liquidity is expensive, but no alternative is deep enough.

Safe‑asset mercantilism and the growth penalty

When a central bank parks export earnings in G‑10 paper, it mops up local liquidity at home. Sterilization drains bank reserves and crowds out private lending. IMF staff estimates show that a 1‑percentage‑point jump in official reserve accumulation lowers EM domestic credit growth by 0.4 percentage points and shaves 0.2 ppts off GDP within a year. Safety, in other words, has an opportunity cost: every extra Treasury bill in Beijing’s vault means one less small‑business loan in Shenzhen.

Can emerging markets mint their safety?

The textbook answer is yes: issue local‑currency bonds, build transparent fiscal rules, and establish an inflation‑targeting central bank. Reality is messier.

- Currency hierarchy Roughly 80 percent of EM trade invoices are still in dollars or euros, so local currency bonds carry an FX mismatch for importers and exporters alike.

- Legal depth Creditor rights hinge on enforceable contracts. Rating agencies embed court efficiency and political risk variables in their sovereign models; trust cannot be decreed.

- Network effects A safe asset is only as valuable as the number of counterparties willing to repo it at haircuts near zero. Building that network takes decades and, often, geopolitical leverage.

Hence the paradox: even after a decade of fiscal reforms, countries like Indonesia and Mexico pay the Fed for swap‑line access instead of issuing quasi‑reserve assets.

Europe tests the supranational route

If sovereignty is scarce, sharing it may be the next‑best option. The EU’s NextGenerationEU recovery plan authorizes up to €712 billion in joint bonds by 2026, and the Commission has already syndicated more than €26 billion in 2025 issuance rounds. A proposal for €150–160 billion per year in defense bonds is advancing, spurred by signals from the US of isolationism. Yet these amounts remain small beside the $23 trillion US Treasury market.

Critically, EU bonds lack a complete banking union and a genuine fiscal backstop, so they trade inside Bund yields only because investors treat them as rare collectibles. Scale them up, and the pricing could change. Northern capitals worry that common debt is a slippery slope toward transfer union, while southern states fear the return of bond‑market vigilantes if Brussels withdraws support. That political tension explains Mario Draghi’s call for an €800 billion-per-year investment drive with new EU‑level revenues.

What happens if the hegemon stumbles?

The Trump administration’s March 2025 tariff threats sliced 7 percent off the DXY in a week and pushed gold to $3,500/oz—a clear vote of no confidence in the dollar’s insulation from political drama. A debt‑ceiling crisis or technical default would trigger a scramble for substitutes, but the menu is thin:

- Euro‑safe assets are Fragmented and capped by internal politics.

- Yen is a deep market, but Japan’s debt ratio exceeds 250 percent of GDP.

- Renminbi Capital controls and legal opacity deter reserve managers.

In short, there is no spare hegemon on the bench.

Policy portfolio: building absolute safety

How much new safety do we need?

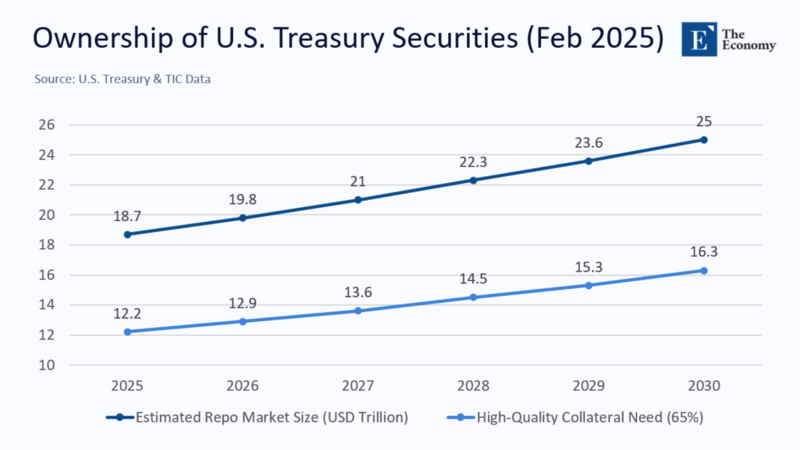

BIS data show that the global repo market adds collateral at roughly 6 percent per year; outstanding repos will exceed $25 trillion by 2030. Assuming investors maintain today’s 65 percent “high‑quality” collateral share, the world needs an extra $5–7 trillion of level‑1 assets within five years—equivalent to the German government bond market.

Only three realistic suppliers exist:

A re‑federalised euro area capable of issuing Bund‑like debt at scale;

A US fiscal adjustment that stabilizes debt service around 2 percent of GDP;

A supranational issuer—the IMF, World Bank, or a G‑20 trust fund—with paid‑in capital and legal seniority over national claims.

Anything short of that trio pushes the system back toward private alchemy.

Credibility is the ultimate collateral

Safe assets are a public good masquerading as a market product. They anchor payment systems, collateralize derivatives, and provide central banks with loss‑absorbing buffers. Because the benefits are global while the costs are national, the supply will always be lower than the first‑best level unless states coordinate.

The next crisis will not begin with a housing bubble; it will start with a confidence bubble in instruments stamped “risk‑free” by convention, not by capability. Regulation can limit the damage but not replace the sovereign promise at the heart of absolute safety. Either political systems find a way to mutualize that promise—through joint debt, multilateral reserves, or credible fiscal anchors—or finance will keep printing ersatz safety until the façade cracks again.

In a world that grows richer yet is politically fractious, the scarcest resource is not capital, technology, or labor. Trust is trust—unlike collateral, it cannot be manufactured in a bank’s back office.

The original article was authored by Madalen Castells-Jauregui, a Senior Economist in the Financial Research Division of the European Central Bank (ECB), along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Who supplies and demands safe assets – and why it matters,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.