Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Prices do not merely rise and fall—they redistribute. Each percentage-point surprise in the consumer-price index quietly rewrites thousands of contracts drawn up in a different price world, shifting resources from one set of hands to another. That rearrangement, long relegated to footnotes in monetary debates, has now burst into the open thanks to the first high-frequency evidence on how stock prices react the instant inflation data are released. The new research, published this week on VoxEU by D’Andrea, Fabiani, Piersanti, and Segura, shows in real time what Irving Fisher could only infer in the 1930s: inflation is a precision tool for relieving debtors at the direct expense of creditors – and the market prices that reality in less than a minute.

In an era of volatile prices and record-high leverage, understanding that silent reallocation is no longer academic. It is the hinge on which business investment, household security, and political legitimacy all turn.

Debt Deflation, Revisited

Fisher’s “debt-deflation” theory, which began with a simple observation, is more relevant than ever in our era of volatile prices and record-high leverage. When an over-indebted economy slips into falling prices, every dollar of debt grows heavier in real terms, forcing firms and families to liquidate assets, cutting demand, and triggering yet deeper deflation. This nine-step chain he described in 1933 still reads like a script for modern crises, from distressed sales to collapsing confidence.

Yet Fisher also hinted at the mirror image: if falling prices intensify debt burdens, rising prices lighten them. A burst of inflation can, in effect, write down every fixed-rate loan in the country without a single line of bankruptcy paperwork. That is the “(de)inflation” half of the mechanism that the new CEPR paper measures.

What the CEPR Study Adds

Using tick-by-tick equity data for U.S. and euro-area firms between 2020 and 2022, the authors isolate stock returns in the narrow window surrounding each monthly CPI release. The three key findings of the study have significant practical implications for businesses and policymakers:

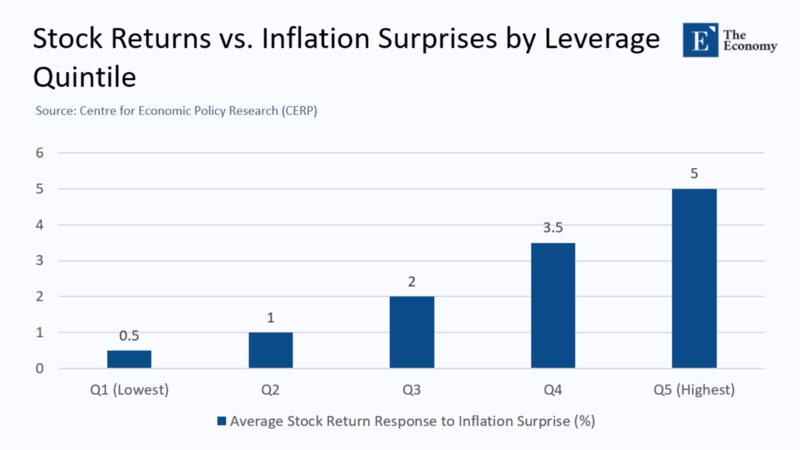

- Leverage drives the windfall. A one-standard-deviation inflation surprise raises annualized returns of the most indebted quintile of firms by roughly 13 percentage points.

- Maturity matters. Only obligations with more than five years to generate the effect; short-term liabilities barely react. That is pure Fisher: the longer the nominal promise, the more inflation erodes it.

- Legal frictions amplify it. The stock-market reward for leverage is significantly larger in countries whose courts are slow to restructure debt. Where judges move at glacial speed, the CPI works as an emergency back-door restructuring tool.

In short, inflation is not an indiscriminate tide; it is a sniper, zeroing in on long-dated nominal claims.

Who Gains, Who Pays?

When a 10 percent inflation shock hits, the arithmetic is brutal. Every 1,000€ bond maturing in ten years quietly transfers about €100 of real wealth from the bondholder to the borrower on day one, and a little more each day, as the higher price level persists. In aggregate, hundreds of billions are being transferred without a parliamentary vote.

- High-debt corporates experience instant balance-sheet relief, higher free cash flow, and—if analysts believe the episode will last—richer equity multiples.

- Property owners watch rents, and replacement-cost values ratchet upward, often indexed formally to inflation.

- Bond investors, pension funds, and retirees on fixed annuities immediately lose purchasing power; many respond by cutting discretionary spending.

- Households with sticky wages endure a wedge between prices at the till and pay packets negotiated a year earlier.

Rocket Money’s plain-language guide to debt deflation lists the first visible casualties: hiring freezes, rising defaults, and a feedback loop into unemployment.The social cost scales far beyond the handful of firms whose share prices pop on CPI day.

Greece: A Case in Debt-Deflation

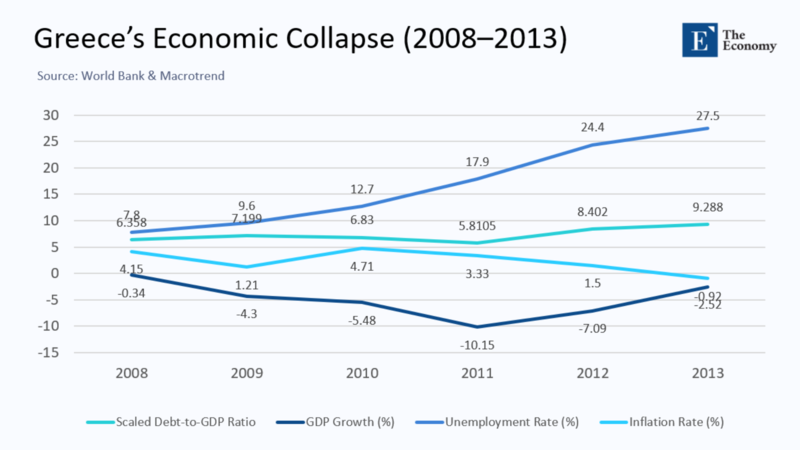

If theory needs a stress test, Greece provides one. Between 2008 and 2013, Greece's GDP contracted by over a quarter, unemployment rose above 25%, and youth unemployment exceeded 50%. Although the euro area denied Athens the option of inflating away its debts, the deflationary half of Fisher’s mechanism played out in full: nominal wages and consumer prices fell, the real burden of public and private debt exploded, defaults mounted, and bank credit collapsed. The social fabric is frayed; an entire cohort emigrated.

The CEPR findings suggest a troubling alternative scenario: If Greece had retained its own currency and utilized inflation to diminish its debts, creditors would have incurred greater immediate losses, but the economy might have escaped years of devastating unemployment. That hard lesson haunts today’s policy debate in Rome, Madrid, and Washington.

Why the Wealth Transfer Hurts Growth

Economists sometimes wave away distributional shifts as a wash: one person’s loss funds another’s gain. That ignores three asymmetries that turn transfers into macro-headwinds:

- There are different spending propensities. Fixed-income pensioners spend most of what they receive; multinational CFOs do not. A euro from the former and handed to the latter reduces near-term demand.

- Risk appetites versus safety needs. Leveraged firms, suddenly flush, often prioritize debt buy-backs or mergers—moves that boost earnings per share but do little for capacity or wages.

- Political representation. Older savers vote at higher rates; hit them hard enough, and policy swings—from sudden rate hikes to price caps—can reverse in ways that destabilize markets.

Inflation’s hidden tax on savers thus chills consumption, distorts investment, and fractures the political consensus needed for long-term reforms.

Why Markets Now Chase Real Assets

The exact mechanics explain why investors rush into property, commodities, and even fine art when they smell sustained inflation. Tangible assets come with self-adjusting price tags, while nominal contracts rot. That flight, however rational individually, bids up housing costs for renters and crowds credit away from productive but less inflation-protected ventures like R&D. Over time, the economy tilts toward rent-seeking rather than innovation.

Policy Implications—Narrative, Not Bullet Points

The implications of this research are profound and should spark a narrative, not just bullet points, in the policy debate. It's crucial to understand that treating two percent inflation as a polite midpoint between zero and danger misses the point. Inflation’s social utility or harm depends on who holds which contracts when the shock arrives. If policymakers allow leverage to build in the private sector and then lean on inflation to clean the slate later, they are, in effect, running an unlegislated wealth tax whose incidence nobody voted for.

A more equitable strategy begins long before prices accelerate. Regulators can discourage excessive long-maturity leverage in boom years, tighten loan-to-value ratios in property markets, and promote inflation-indexed savings instruments that shield the lower and middle classes. Courts can be funded to expedite restructuring so that legal efficiency, not unexpected CPI spikes, decides which debts survive. And when inflation flares, automatic cost-of-living adjustments on public pensions and basic wages can prevent the immediate purchasing-power shock that curtails consumption.

Some economists propose a temporary windfall levy on the unearned revaluation of real-estate portfolios—a reversal of the stealth subsidy landlords receive when rents reset upward. Such tools are controversial, but they at least name the transfer and debate it openly instead of letting the price level do the politics in darkness.

The Stakes in 2025 and Beyond

The global disinflation of late 2023 has lulled many governments into thinking the episode is over. Yet the debt stock built during the zero-rate decade remains, waiting for the next geopolitical jolt or climate-related supply shock to test it. When that test comes, the distributional lens Fisher offers—and quantified by the CEPR team—will be essential. Without it, central banks risk aiming policy at abstract aggregates while society experiences concrete, asymmetric pain.

Failing to anticipate that pain invites populist backlashes, abrupt policy U-turns, and capital-allocation mistakes that linger long after the price spike subsides. Greece’s lost decade is a warning; the market’s split-second response to CPI numbers is a real-time reminder.

Repricing Promises, Rewriting Power

Inflation is not simply a movement in an index. It is a re-pricing of promises, a re-ranking of creditors and debtors, a quiet coup that changes who can spend, who must save, and who gets to shape the following policy. Fisher sensed that truth ninety years ago; the CEPR evidence lends complexity to it. For governments that prize social cohesion and investors who assume today’s winners will remain at the top, ignoring the coup is no longer an option.

The original article was authored by Angelo D'Andrea, an Economist at the Financial Stability Directorate of the Bank of Italy, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled " The Fisherian debt (de)inflation channel and stock returns,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.