Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

“The hand that holds the purse writes the rules.” For half a century, that hand belonged to Washington. Today an equally firm grip comes from Beijing, and the rules of development finance are being redrafted in real time. China’s transformation from capital‑hungry manufacturer to capital‑exporting creditor is the least‑examined upheaval of the post‑Bretton Woods order, yet it already shapes the fate of treasuries from Lusaka to Lahore.

A Quiet Balance‑Sheet Revolution

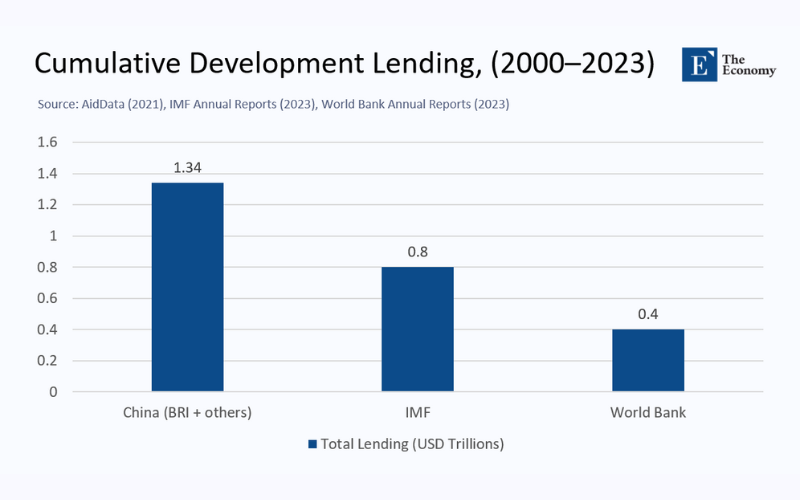

During the long 1990s, China absorbed rivers of foreign direct investment—on average, $ 115 billion a year. That torrent has slowed to a trickle. In 2023, net FDI inflows collapsed to $ 42 billion, their weakest level since 1993, as pandemic scarring, a domestic real-estate bust, and Western export controls chilled sentiment. The savings that once sought outside capital now seek yield abroad, and Beijing has chosen to recycle them through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). AidData estimates that Chinese development finance between 2000 and 2023 reached $ 1.34 trillion—already larger than the historical cumulative lending of the IMF and the World Bank. In a single business cycle, the world’s largest former borrower has become the dominant official creditor in the Global South.

A Distinctive Business Model

Unlike Washington‑Consensus loans, Chinese credit is neither concessional aid nor pure commercial paper; it occupies a grey zone where statecraft and profit merge. Four to five percent interest coupons arrive faster than any Western alternative yet remain well below junk‑bond yields. Maturities rarely exceed ten years, grace periods seldom surpass two, and collateral clauses are the norm rather than the exception. Whether a port in Sri Lanka or a power grid in Pakistan, the asset itself often secures the advance, its future cash flow diverted into offshore escrow long before local taxpayers see it. The speed at which Chinese banks can approve and disburse first tranches within months, because state-owned contractors handle environmental and social safeguards in-house, is a testament to their efficiency.

Collateral and Consequences

The practice generates a paradox. On the one hand, physical guarantees lower Beijing’s credit risk and unlock funding for projects too large or too politically risky for Western lenders. Conversely, those same guarantees turn strategic infrastructure into a valuable asset at the negotiating table. Sri Lanka’s 2017 decision to cede a seventy‑per‑cent stake and a ninety‑nine‑year lease on Hambantota Port after failing to service a 1.3 billion‑dollar loan was more than a balance‑sheet adjustment; it transferred a potential naval foothold barely two sailing days from India’s coast. A similar dynamic emerged in Kenya when leaked loan documents suggested that the Standard Gauge Railway's default could lead to Mombasa Port being placed under Chinese control. In Laos, the high-speed rail line to Kunming may reduce logistics costs by a third; however, its revenues flow directly into a bank account managed in Beijing, leaving Vientiane responsible for sovereign guarantees should freight projections fall short.

Two Liquidity Tides

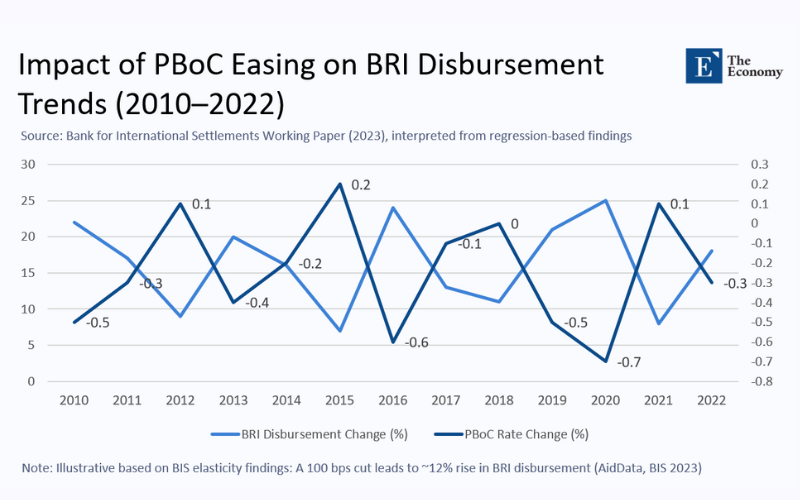

For decades, the cost of capital in emerging markets fluctuated in tandem with the U.S. federal funds rate. That neat correlation is breaking down. Econometric work by the Bank for International Settlements shows that a one‑percentage‑point easing by the People’s Bank of China boosts overseas disbursements by roughly twelve percent within a year, partially offsetting the effects of Federal Reserve tightening. Frontier governments now navigate two monetary tides—one denominated in dollars, the other fueled by renminbi‑funded policy banks. Risk models that fail to incorporate Chinese credit shocks, regulators warn, systematically understate tail risks.

This figure illustrates the observed correlation between China's domestic monetary easing and corresponding increases in Belt and Road disbursement activity, as interpreted by the BIS and AidData. A 100 basis point cut in policy rates is typically followed by a ~12% increase in BRI lending within 12 months.

Winners, Losers, and Grey Zones

The new landscape is not zero‑sum, yet value accrues asymmetrically. Borrowing nations receive express‑lane infrastructure—from highways in Serbia to power plants in Nigeria—without waiting years for World Bank appraisals. The price is a steeper coupon, a shorter tenor, and reduced bargaining power when commodity booms fade. Chinese state‑owned enterprises lock in foreign contracts, secure above-treasury yields, and acquire strategic toeholds along the maritime arteries that carry their export economy. By contrast, western lenders and EPC contractors find themselves crowded out, constrained by Basel capital rules, and vexed by the impossibility of matching Chinese execution speed.

Local communities experience a mix of promise and peril. New bridges light up at night; new trains cut travel times in half, yet displacement disputes flare, tariff hikes follow, and environmental oversight often arrives after cement trucks departures. The BRI’s most significant selling point—its velocity—can also be its gravest flaw because shortcuts around social safeguards almost always emerge as fiscal liabilities down the road.

Systemic Fault Lines

Opacity tops the list of macro‑risks. AidData reckons that roughly half of Chinese loans evade sovereign debt statistics altogether. That blind spot inflates the price of bonds and distorts IMF sustainability analyses. When distress surfaces, workouts stumble. Zambia waited twenty‑two months between default and a memorandum of understanding because Beijing and Paris Club creditors argued over comparable treatment. Sri Lanka’s restructuring talks are inching through a third year, with Chinese lenders reluctant to share their haircut calculations.

Environmental and social externalities compound the problem. Rapid execution sidesteps the safeguard frameworks that multilateral banks spent decades refining, raising the rate of cost overruns and fuelling community protests. Finally, collateral clauses give Beijing diplomatic leverage that is subtle yet potent. Scholars mapping UN voting patterns find a measurable tilt toward China’s foreign policy preferences among heavy BRI borrowers, particularly on sensitive human‑rights resolutions.

Toward a Dual‑Anchor Architecture

Containment is an illusion; Beijing’s balance sheet is too large and deep in the field to be fenced off. The constructive path lies in transparency and competition. A sovereign collateral registry hosted by the G‑20 would make security clauses visible, reducing the number of surprises that roil bond markets. Export‑credit agencies in the West could revitalize blended‑finance vehicles, providing first‑loss guarantees that shave a hundred and fifty basis points off private coupons—enough to challenge Chinese banks on price without mirroring their collateral practices. The urgency and necessity of transparency and competition in global finance cannot be overstated, and these changes could bring about a more balanced and fair system.

For their part, multilateral lenders should codify “strategic‑asset safe zones,” designating telecom backbones, major ports, and grid interconnectors as untouchable in debt workouts in exchange for super‑senior status on new money. Borrowing nations would do well to adopt laws requiring parliamentary ratification for any loan secured by resource or infrastructure collateral. Such statutes would raise the political cost of opaque deals and perhaps nudge negotiations into daylight.

Finally, a green‑conditionality swap could turn a source of rivalry into a channel of cooperation. Projects that meet Paris‑aligned emissions thresholds—verified by independent auditors—could earn coupon rebates financed jointly by Western climate funds and Chinese policy banks. The incentive structure would realign sovereign‑borrowing costs with global public goods at a stroke.

A New Grammar of Power

Development finance no longer speaks a single language of concessional aid. It is now bilingual. One dialect prices money in basis points; the other prices it in barrels of oil, cargo throughput, or ninety‑nine‑year leases. Sovereigns that master both dialects diversifying their creditor mix and arbitraging conditionality, will secure the capital they need without pledging crown jewel assets. Analysts can no longer ignore Beijing’s balance sheet; policy‑makers must shape its incentives; investors must trace the collateral trail with forensic care. And citizens in borrowing nations—those whose ports, railways, and power lines hang in the balance—must learn this new grammar quickly, lest the infrastructure that empowers them today slip from their grasp tomorrow.

China’s rise as an international lender is not a postscript to globalization; it is the next chapter, and the pen has already etched the first lines.

The original article was authored by Zhengyang Jiang, an Associate Professor of Finance at Northwestern University. The English version of the article, titled "The rise of China as an international lender,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.