Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

As you walk through Seoul’s sprawling Namdaemun Market this spring, the urgency of the situation becomes palpable. Stalls that once stocked Korean-made rice cookers and Japanese hair dryers now display Xiaomi robotic vacuums marked down by forty percent as the Beijing electronics giant blitzes the peninsula with its first large-scale discount event in two years. At the exact moment, the Korean Customs Service is scrambling to stem a wave of mislabeled Chinese goods—₩29.5 billion worth in the first quarter alone—shipped through Korea to dodge Washington’s new 145 percent tariff.

These scenes appear far removed from the tidy conclusion of Simon Evenett’s recent VoxEU column, which, relying on highly granular 2024 U.S. import records, downplays the global spill-overs of America’s tariff barrage. Evenett finds that most Chinese products, which had already lost ground in the United States before the tariff hike, have not yet shown signs of rerouting to third markets. The methods are rigorous, yet the inference—that the fight is essentially a bilateral matter—fails to capture what is unfolding on the ground in East Asia and, increasingly, in Europe. The reason is not flawed econometrics, but timing: a capacity shock of this magnitude moves like a slow-rolling wave. By the time it crests on U.S. shores, it has already drenched America’s manufacturing allies.

Why the Data Lag Behind Reality

Three mechanics explain the disconnect, each adding a layer of complexity to the issue. First, China entered 2024 with swollen inventories. Running those stockpiles down suppressed new export bookings, so customs data offered an artificially calm picture. Second, mislabeling and trans-shipment—classic mirror-statistics distortions—shift flows from easily searchable U.S. databases to the much murkier ledgers of transit states. Korean officials concede that ninety-seven percent of the origin fraud cases they uncovered this year explicitly aimed at bypassing American duties. Finally, policy counter-moves outside the United States arrived late. Brussels did not unveil provisional anti-subsidy duties on electric vehicles until October 2024. Seoul’s provisional penalty on Chinese heavy steel plate, peaking at thirty-eight percent, took effect only in February 2025.

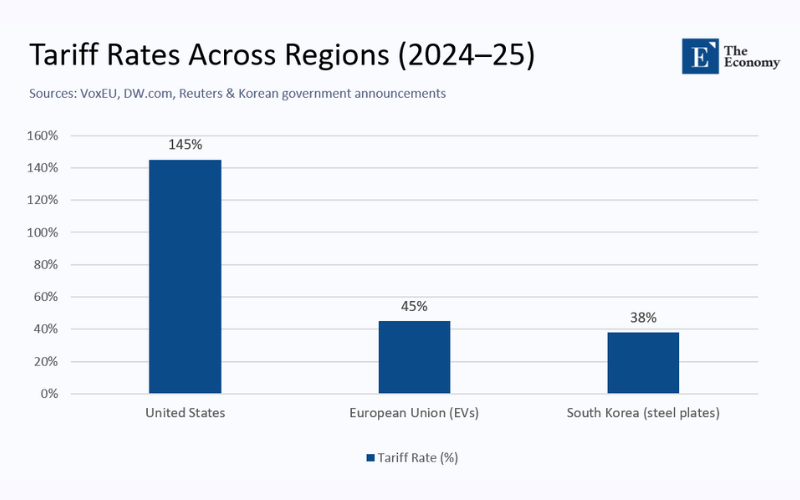

The chart displayed earlier distills the new tariff topography. Washington’s wall soars to one hundred forty-five percent, dwarfing Europe’s forty-five percent ceiling on EVs and Korea’s upper thirty percent brackets on specific steel forms. That differential means that all Chinese exporters are required to clear unsold inventory elsewhere.

A Capacity Glut Looking for an Outlet

China’s industrial overhang is no longer speculative. Official customs figures indicate that outbound shipments accounted for thirty-two percent of global trade value in 2024—a record share. In automobiles, the imbalance is stark. Chinese electric vehicles now retail at or below the cost of comparable internal-combustion cars, and lithium-iron-phosphate battery packs run up to thirty percent cheaper than U.S. or EU equivalents. Domestic demand, dampened by a soft property market and cautious consumers, cannot absorb the surge, so factories must either idle or dump abroad. Most choose the latter; the first floodgate opened in intermediate steel.

Imports of Chinese heavy plates into Korea surged to $10.4 billion in 2024, accounting for nearly half of Korean demand. Executives at POSCO warned of potential furnace shutdowns, prompting the government to declare an emergency duty. Had an analyst looked only at U.S. steel-plate manifests, she would have missed this torrent. A similar dynamic is emerging in the white goods sector. Korean customs statistics, though released only in aggregate, point to a seventeen-per-cent year-on-year jump in Chinese appliance imports during the first quarter of 2025, even as Korea’s exports of these items to the United States fell twelve percent. The goods are not merely in transit; they are priced to dislodge domestic brands on their home turf.

Europe’s Turn in the Crosshairs

On the other side of Eurasia, Brussels has begun to grasp that it is next. The Commission’s probe calculated that Chinese-branded EVs leaped from less than one percent of European registrations in 2019 to eight percent in 2024 and could surpass fifteen percent this year without intervention. The resulting duties, which can amount to up to forty-five percent, are designed to neutralize subsidies. Yet, the margin still allows cut-price brands such as BYD, MG, and Nio to expand, particularly in price-sensitive southern and eastern member states.

The stealthier beachhead is appearing in components. German port records reveal a thirty-four-per-cent spike in Chinese battery-module imports in the second half of 2024, with products coded differently from complete vehicles and thus slipping beneath the anti-subsidy radar. Reuters, citing leaked drafts, reports that Commission staff are already designing an “emergency brake” that could lower steel-import quotas by 15 percent should another surge materialize. Such contingency planning hardly squares with the notion of limited collateral damage.

Why Relocation Will Not Absorb the Shock Overnight

Multinationals from Apple to Adidas tout plans to reroute assembly lines to India, Vietnam, or Mexico. Apple has even pledged that every iPhone sold in the United States will be assembled in India by the end of 2026. Diversification is real, but three structural frictions slow its cushioning effect. Upstream choke points—such as cathodes, permanent magnets, and specialty glass—remain overwhelmingly Chinese; shifting final assembly leaves component exports largely untouched. Scale is another hurdle. Shenzhen’s electric-vehicle clusters now churn out ten million units annually, whereas all Indian auto exporters combined shipped 725,000 cars in 2024. Bridging that gap will take years, not quarters. Finally, Beijing has already weaponized export licenses on gallium, graphite, and other rare earth to warn firms that migration carries a price. Even if diversification accelerates, the intervening period is perilous for middle-income manufacturing neighbors. Underutilized Chinese factories with high fixed costs are incentivized to undercut global prices in order to keep their lines running.

What the Numbers Say Once the Blind Spots Are Filled

A more forward-looking lens suggests the redirection wave may be sizeable, potentially altering the global trade landscape. Consider steel. If merely one-fifth of the fifteen billion dollars worth of Chinese steel now effectively locked out of the U.S. market is diverted to Korea and Japan at a twenty-five percent discount, local producers stand to lose roughly three billion dollars in annual revenue—about eleven percent of POSCO’s 2024 sales. In 2022, Europe registered 350,000 electric vehicles with Chinese branding. Should excess capacity equivalent to another half-million cars be unloaded at a four-thousand-euro price advantage, Chinese market share would exceed 20% by 2026, effectively swallowing the volume growth that European groups, such as Renault and Stellantis, currently project. These upper-bound estimates assume no further policy defense, yet they already dwarf the “limited threat” implied by a U.S.-centric dataset.

Policy Choices in a No-Win Landscape

Governments caught in the middle now confront difficult trade-offs. Seoul’s rapid anti-dumping response provided breathing space, but constant litigation is expensive and invites friction with the WTO. Tightening rules of origin through blockchain certificates and forensic audits can raise violators’ costs, yet demand sophisticated customs capacity. A more effective strategy is to subsidize the domestic production of choke-point inputs, so that entire supply chains, rather than just final assembly, are anchored locally—Japan’s 2024 subsidies for two-nanometre chip fabs exemplify this approach. None of these tools is inexpensive, and each carries the risk of retaliation, but complacency seems riskier. At the same time, President Trump signals that he may impose a blanket ten-per-cent tariff on all imports, friend and foe alike, during his first budget submission this summer.

The Battle for the World’s Middle Corridors of Trade

The tariff war has outgrown its bilateral cradle. It is now a contest over which corridors will absorb China’s excess capacity. The first fissure—heavy plate and home appliances in Korea—has opened wide; the second—European battery modules—is widening by the month. Evenett’s meticulous micro-evidence remains valuable as a snapshot of 2024, but snapshots freeze the past. A dynamic perspective, informed by mirror statistics, inventory cycles, and reactive policy, reveals a global trading system at risk of bifurcating along corridors rather than continents.

For Seoul and Tokyo, the warning clangs through falling producer prices and a spike in anti-dumping petitions. For Brussels, it resonates in committee rooms as drafters work on ever-broader safeguard clauses. For trade economists, it signals that analytical comfort zones anchored to U.S. customs data may now overlook the most consequential currents in world commerce.

America’s tariff wall stands 145 percent tall. As engineers know, water will always find the lowest point of entry, and in 2025, that point will be breached first against the East China Sea and the Rhine. Whether those levees hold will decide who prospers and who founders in the next chapter of the tariff era.

The original article was authored by Simon Evenett, a Professor of Geopolitics and Strategy at IMD Business School. The English version of the article, titled "Identifying potential Chinese export redirection in 2024 US trade data,” was published by CEPR on VoxEU.